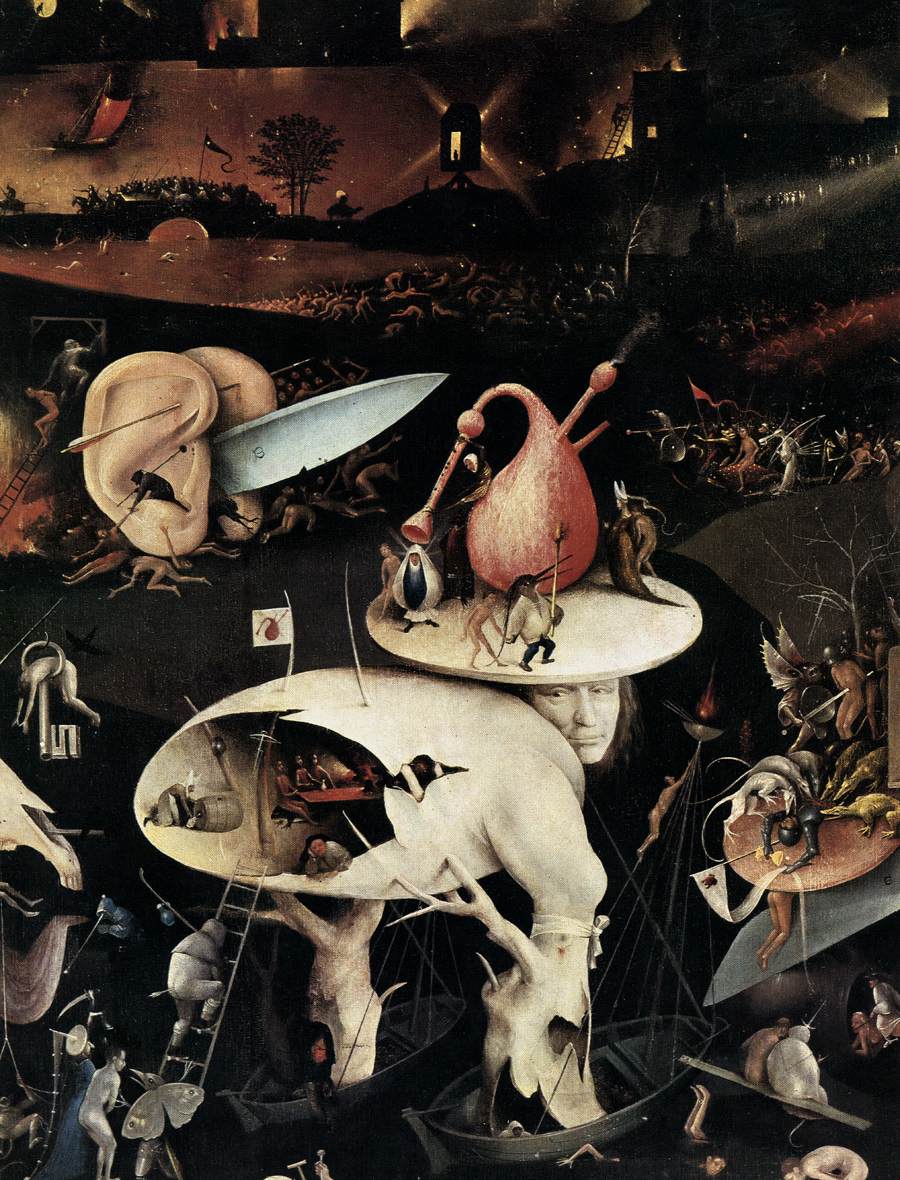

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych oil painting created between 1490 and 1510 by the Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch. You have probably seen it before, somewhere online. The painting’s three panels are filled to the brim with scenes so absurd they’re hard to describe.

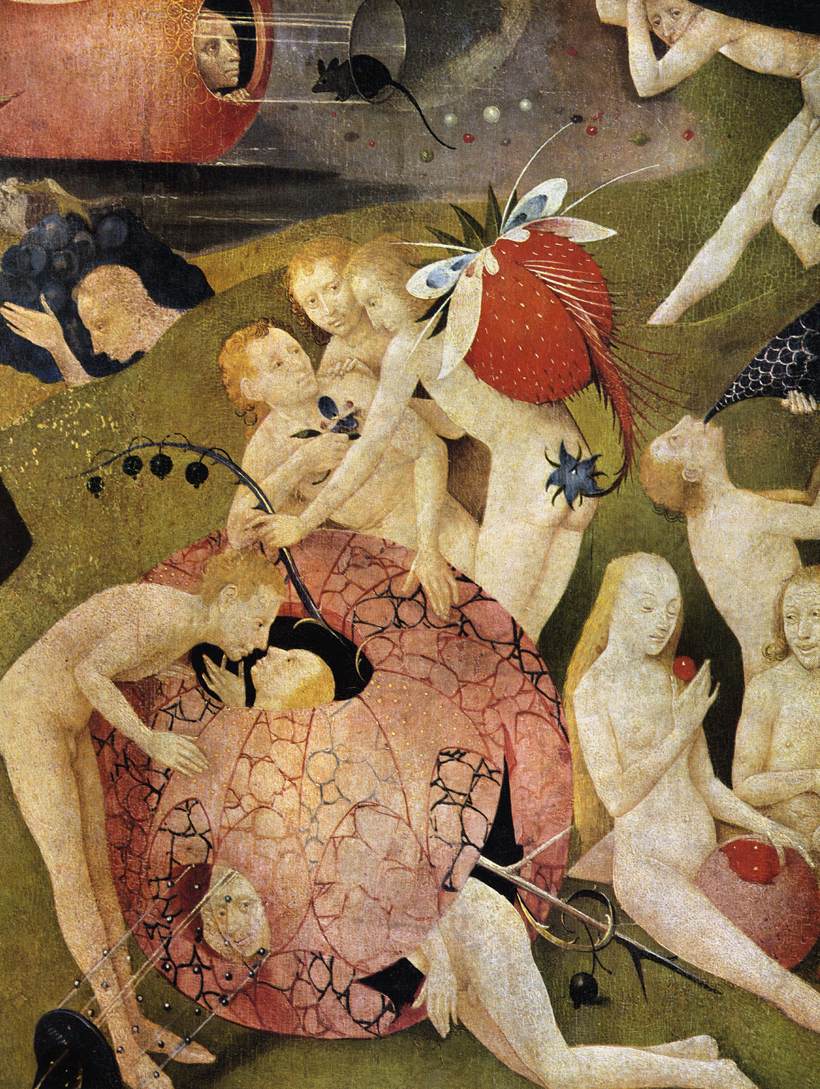

Most involve naked people. Naked people frolicking through lush green fields and fornicating in cubist-looking fountains. Naked people stuffing flowers up each other’s rectum, gathering beneath giant strawberries, or emerging from equally massive eggs. Naked people being consumed by a creature with the head of an owl wearing a kettle for a hat.

Despite its bright colors and smiling subjects, The Garden of Earthly Delights strikes us as a deeply disturbing painting. Its nonsensical imagery and realistically rendered dreamscapes are similar to the works of surrealist painter Salvador Dalí or the images produced by Google’s DeepDream algorithm. These qualities made Bosch’s masterpiece a must-see back in its day, and they explain its enduring popularity in our own time. But what does it mean?

The mysterious life of Hieronymus Bosch

Part of the allure of The Garden of Earthly Delights comes from the fact that we know very little about its creator. The life and career of painter Hieronymus Bosch had to be pieced together from a collection of 53 historical documents. Some were written by Bosch himself. A few were written by others and only mention him in passing. Most are simple bills and tax receipts.

Bosch was born in 1450 as Jheronimus van Aken. “Hieronymus Bosch” was his artist’s name. He borrowed it from his birthplace, the Dutch city ‘s-Hertogenbosch, or Den Bosch for short. His two brothers were painters. So were his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather.

A document from 1481 reveals that Bosch was married to Aleid van de Meervenne, whose wealth and status offered him access to Den Bosch’s most exclusive social circles. Among these was a quasi-religious organization called the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, whose members included heirs of major European families. The purpose of the Brotherhood was charity. However, documents reveal that Bosch mostly threw lavish dinner parties in the company of his sworn brethren, where they dined on costly Netherlandish delicacies like swan meat.

Devils, buttocks, and cod-pieces

Because Bosch’s personal beliefs were unknown, his paintings were often taken at face-value. Failing to recognize The Garden of Earthly Delights as a depiction of the Garden of Eden (the title was attributed retrospectively by critics), contemporary viewers mistook the work’s religious imagery for meaningless fantasy, a categorization that subsequent scholars readily adopted.

In his 16th century book Description of the Low Countries, the Venetian merchant Ludovico Guicciardini proclaimed Bosch “the most noble and admirable inventor of things fantastical and bizarre.” His contemporary Giorgio Vasari called Bosch’s paintings “capricious” which, in the Italian tradition, referred to images of the imagination rather than reality. Vasari’s comment was positive, but the poet Francisco de Quevedo was more critical when he wrote that Bosch’s oeuvre could be reduced to “devils, buttocks, and cod-pieces.”

Bosch appears to have embraced his reputation as a medieval imagineer. His notebooks contain several sketches of monsters. These look more like doodles than preparations for paintings. Bosch, in other words, created them for his own amusement rather than to make a point. In his panel John on Patmos, one of Bosch’s monsters also appears to interact with his own signature, betraying an affectionate connection between the man and his Frankensteinian inventions.

Monsters in medieval manuscripts

Art historians have likened these inventions to drolleries, a term used to describe the peculiar drawings that populate medieval Europe’s illuminated manuscripts. Drolleries vary widely from page to page. Some are faithful representations of real-world animals and objects. Others are chimeras — combinations of elements that don’t belong together, like penises on legs.

The logic behind and significance of drolleries has continued to elude medieval scholars. The only thing they appear to have in common is their placement in the margin of the text. This suggests they serve a purely decorative purpose, and that they are not related to the contents of their manuscripts. One 2014 article refers to drolleries as “a spatial mardi gras where everything was allowed.”

Like Bosch, the art of drolleries was not without its critics. Horace dismissed them because, according to him and other Roman writers, art was supposed to imitate nature. Since fantasy made a mockery of nature, it ought not to be taken seriously. Horace’s opinion survived into the Dark Ages, where it acquired a new and distinctly religious significance as clergymen began to fear that people were more interested in the margins of illuminated manuscripts than they were in the manuscripts themselves.

Decoding The Garden of Earthly Delights

Subsequent generations of art historians recognized Bosch’s paintings for the sophisticated and multilayered visual commentaries they (probably) are. The Garden of Earthly Delights, for its part, has been revisited through the lenses of alchemy, astrology, and folklore, which yield a number of possible explanations for the seemingly nonsensical scenes.

As evident by its title, the triptych is now widely interpreted as a condemnation of lust. Such a conclusion was reached through iconography, the study of the symbolic meaning of objects and how that meaning changes over time. The central panel, for instance, is filled with objects that, in the 16th century, represented the transience of earthly beauty and sexual appetite, including bulls and hollow fruit. The owl, meanwhile, was a symbol of witchcraft, also used effectively by Goya.

There are other interpretations, too. The famed art historian Ernst Gombrich once argued the triptych represents “the state of mankind on the eve of the Flood, when men still pursued pleasure with no thought of the morrow.” The most radical hypothesis has come from Wilhelm Franger, who believes The Garden of Earthly Delights is not a condemnation of lust but a celebration of it. Bosch, he writes, may have been commissioned or inspired by the Adamites, a Christian sect which proclaimed that mankind, like Adam and Eve, should not be ashamed of their humanity.