How Frank Herbert’s “Dune” revolutionized science fiction

- Wanting his fictional world to feel real, Frank Herbert incorporated many real-world analogs.

- Going the extra mile, he also made sure that the history of his world was as complex as our own.

- These details are hardly emphasized in the main story, only appearing in appendages.

Before he became a science fiction writer, Frank Herbert worked a number of odd jobs. In 1957, while earning a living as a journalist, Herbert traveled to the state of Oregon to write an article on how the state government was using poverty grasses to stabilize the sand dunes that stretched along the coastline. Impressed by the size and scope of the Pacific Northwest, whose natural landscape seemed to dwarf even the largest cities to which he had been, Herbert never finished the writing assignment. Instead, parts of his mind began working on what would become the most influential science fiction novel in the history of the genre.

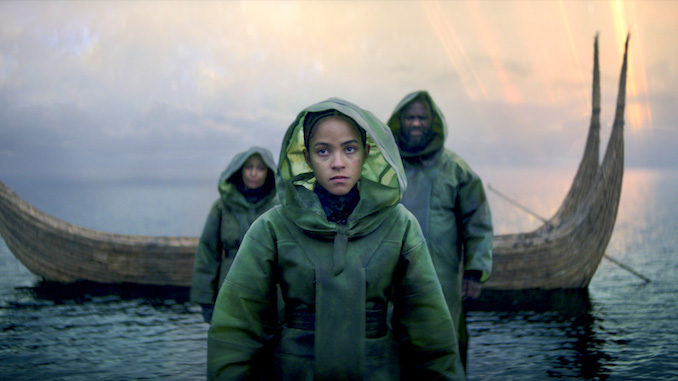

Today, we know this novel as Dune. It was originally published in 1965 and serves as the foundation for Denis Villeneuve’s epic film, which just released in cinemas around the world to both critical and commercial acclaim. It is set in a fictional and very distant future, one in which mankind has managed to colonize even the remotest corners of the galaxy. Its protagonist is Paul Atreides, the prepubescent heir to an ancient, aristocratic family that — sometime before the start of the story — was granted stewardship of the desert planet Arrakis. Their job is to oversee the mining and export of a spacetime warping, life-extending drug known as spice melange, which can be found only on Arrakis.

When readers were first introduced to the world of Dune back in the 1960s, they quickly discovered that it was unlike any fictional universe they had yet come across. George Lucas was years away from writing the first draft of Star Wars. Science fiction was still in its infancy and usually appeared in the form of short stories that were published in pulp magazines like Amazing Stories. Generally, these stories were far more concerned with crafting a suspenseful plot or exploring an interesting idea about human nature than they were with establishing a living, breathing alternate reality. Herbert’s Dune accomplished the latter without losing sight of the former.

Rethinking science fiction

Of course, Herbert was not the first to try his hand at constructing such a reality. More than a decade before he published his magnum opus, the British linguist and fantasy writer J.R.R. Tolkien had already beaten him to it. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy expanded the borders of Middle-Earth as they had been outlined in his earlier work, The Hobbit. Appendices containing the histories of kingdoms and their royal lineages made the stories they bookended feel increasingly believable. But where Tolkien drew inspiration from English and Gaelic folklore, Herbert’s academic interests lay elsewhere. The source material he transformed into Dune was found not in myth but history.

Those familiar with Dune can pinpoint numerous connections between Herbert’s imagination and the real world that stimulated it. Since the story takes place in a future version of our actual universe, it only makes sense that the societies portrayed in Dune should bear traces of their present-day counterparts. In Dune, the planets colonized by humanity are organized into a feudal system called the Landsraad — a word borrowed from Danish meaning “land council.” Herbert’s choice to use a foreign term as opposed to an English one hints at the possibility that the book’s galactic empire is Scandinavian in origin, or at the very least based on European feudalism.

Similarly, many characters — despite living in an entirely different millennium — have modern-day surnames. For instance, the right-hand of the novel’s main antagonist, Atreides’ archrival Vladimir Harkonnen, is named De Vries, which is a surname that comes from the Friesland region in north Netherlands. Likewise, spice melange, the rarest and consequently most valuable commodity in the known universe, is a clear analog to natural resources like oil and gas. As with the spice, these substances are found only in select places across the globe, and their presence (or absence) has major consequences for human development and international relationships.

The history of Dune

Though Herbert tried to make his writing accessible to a large number of readers, he also wanted to satisfy his own academic interests. To make his fictional universe feel as realistic as possible, he made sure that the history of the Dune universe was just as complex as our own. It is, for example, no coincidence that the planets mentioned in the story are united under an emperor and organized in a fiefdom-esque system. Centuries before the start of the novel, humanity was forced to the brink of extinction by machines. When they finally managed to turn the tide, the survivors of this conflict (later named the Butlerian Jihad) resolved to outlaw the creation of artificial intelligence.

This resolution — “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind” — became the central commandment of civilization moving forward and helps explain why the societies featured in Dune are not as advanced as one might expect. Culturally, the Butlerian Jihad also appears to have sent society back to a semi-medieval state. For instance, readers may be surprised to find that religion is alive and well in Herbert’s distant future, playing a far more important role than it does in our time. At some point during their odyssey into deep space, humanity combined all “old world” religions into a single humanitarian text.

This text, known as the Orange Catholic Bible, is one of the most influential pieces of writing in all of the Dune universe. Its spiritual teachings, a collection of common themes taken from both monotheistic and polytheistic religions, serve as guiding principles for how citizens of the galactic empire should behave and approach the concept of progress. Its supreme commandment, “Thou shalt not disfigure the soul,” is itself a variation on the lesson learned from the Butlerian Jihad.

Many of these insights do not appear in Villeneuve’s film. They aren’t even emphasized in the novels but can be gleaned from appendages and indices at the end of each book. It is in these often overlooked pages that Herbert’s genius (and the revolutionary impact he had on the science fiction genre) lies hidden.