Devil’s advocate used to be an actual job within the Catholic Church

- In the 16th century, Devil’s advocates argued against the canonization of saints.

- Advocates cross-examined witnesses and questioned evidence to disprove the authenticity of miracles.

- Today, the profession’s legacy lives on not through religion, but science.

The original meaning of the term “Devil’s advocate” strongly resembles its contemporary one. Today, it refers to someone who argues in favor of a proposition they do not necessarily agree with or believe in, usually in the interest of debate.

Centuries ago, Devil’s advocate was an actual job within the administration of the Roman Catholic Church. Whenever the Church considered declaring somebody a saint, the Devil’s advocate — also known as the advocatus diaboli or the Promotere Fidei (Latin for “promoter of the faith”) — would argue against the candidate’s nomination.

Devil’s advocates did so by examining evidence on the miracles that were connected to the candidate. They also cross-examined witnesses and looked for flaws in the candidate’s character. Devil’s advocates were pitted against God’s advocate, also known as an advocatus Dei, or Promoter of the Cause. Like lawyers in a secular court, these magistrates used their oratory skills in an attempt to convince the jury presiding over the candidate’s sainthood.

The origins of the Devil’s advocate

As the scholar Paolo Parigi explains in his book, The Rationalization of Miracles, the history of the Devil’s advocate can be traced back to the formation of the Congregatio Sacrorum Rituum, a special commission created by pope Sixtus V in 1588 with the purpose of investigating people who were believed to have performed miracles in their lifetime and, as such, qualified for sainthood.

The Congregatio — and, by extension, the position of Devil’s advocate — were created for several reasons. Europe in 1588, explains Parigi, was “an environment lacking the many taken-for-granted beliefs that characterized the preceding centuries.” The authority of the Church, once unquestioned, was now being challenged on multiple fronts.

According to Parigi, the Devil’s advocate played a small yet crucial role in a wider effort to regulate the canonization process. Such regulations would not only silence Protestants who were skeptical of the Vatican’s integrity, but also prevent local mystics from acquiring autonomous followings that could fracture the unity of the Catholic Church itself.

Canonization before Sixtus V

Although the term Devil’s advocate did not become commonplace until after 1588, the job itself predates the Congregatio by several centuries. As the scholar Leonardas V. Gerulaitis suggests in his article, The Canonization of Saint Thomas Aquinas, the responsibilities of the Devil’s advocate used to fall to a group of commissioners while those of God’s advocate fell to a proctor.

During canonization in the fourteenth century, the proctor would round up witnesses who could vouch for the miracles connected to the candidate. After these witnesses shared their testimonies, they were questioned by the commissioners. According to one primary source cited by Gerulaitis, they were asked to give the exact dates and places of miracles, among other things.

Commissioners kept their eyes peeled for contradictions between testimonies. All hearings and interrogations were documented and presented to a committee consisting of bishops, priests, and cardinals who in turn advised the pope. Though there was usually one proctor, there were multiple commissioners; the profession of Devil’s advocate further simplified the canonization process.

Defining supernatural boundaries

Every case provided the Devil’s advocate with unique challenges. Sometimes, the testimonies on miracles conflicted with one another. At other times, the only witnesses to a miracle were women or children, neither of whom were seen as reliable in the eyes of Church administrators of the time. In these instances, it was up to the Devil’s advocate to lend them credibility.

As mentioned, Devil’s advocates played but a small role in the Church’s attempt to formalize the canonization process. Despite this, the profession had some major religious implications. As Parigi puts it, the work of the Devil’s advocate was about “defining the boundaries of the supernatural” by determining what could and could not be considered a genuine miracle.

“The task of the Devil’s advocate,” Parigi continues, “was not to deny the existence of miracles but to create space for false miracles – that is, for the occurrence of events or facts that, although inexplicable by science or medicine, were nevertheless not true miracles. Doing so legitimized the claim of the Church to be the guardian of the supernatural.”

The Devil’s advocate diminished

The Devil’s advocate was part of the Roman Catholic Church for more than 400 years, until John Paul II greatly reduced the profession’s powers in 1983. Why he did this, no one knows for certain. What we do know is that this action has greatly increased the speed at which the canonization process takes place, and that it gave the figure of the pope greater control.

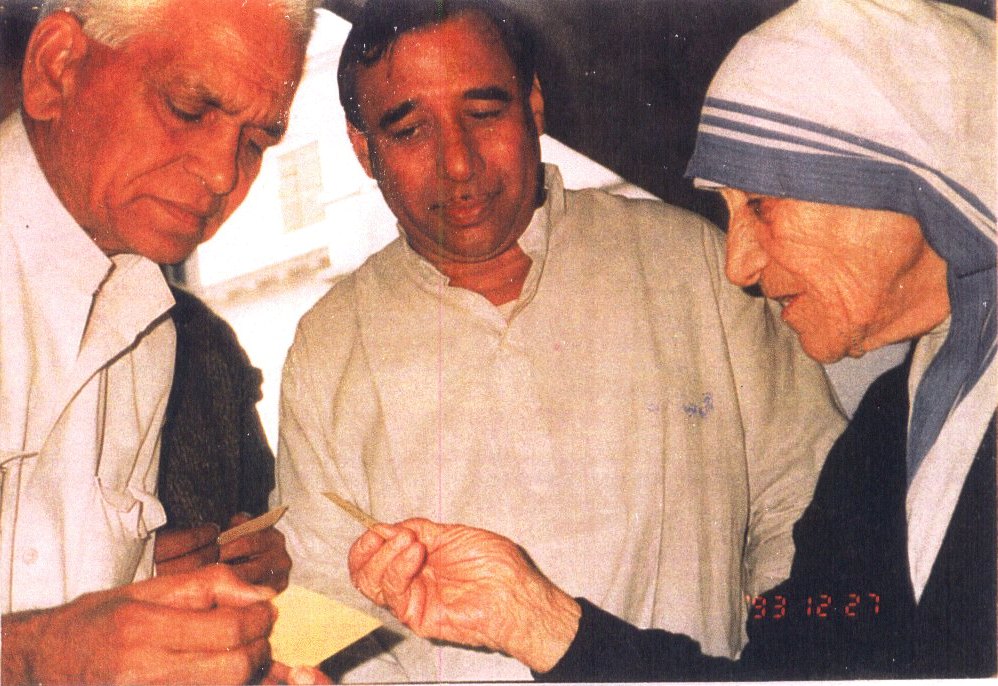

Although the profession no longer exists today as it did once, the Vatican still occasionally solicits testimony from critics when reviewing new candidates. This happened in 2003, when the atheist author Christopher Hitchens was interviewed during the canonization of Mother Teresa. Hitchens’ criticisms, later published by Slate magazine, were aimed at Mother Teresa specifically, as well as the Catholic Church in general.

Like a proper Devil’s advocate, Hitchens questioned the authenticity of Mother Teresa’s miracles. When the Church defended a Bengali woman who claimed that a beam of light emerging from Teresa’s picture cured her tumor, Hitchens called on the woman’s doctor, who said her cancer was a tubercular cyst that disappeared thanks to prescription medicine. Hitchens also criticized Teresa’s opposition to female empowerment, birth control, and planned parenthood.

Validating saints

Hitchens was also angry with the pope, who in his eyes had diminished the importance of the Devil’s advocate to make the canonization process quicker and less rigorous. When Mother Teresa was declared a saint, she had only been dead for a year. Previously, candidates had to have been dead for at least five years before they could qualify for sainthood.

At first glance this may sound like a trivial bureaucratic rule. However, Hitchens argues this rule was put in place for a reason. Without Devil’s advocates to oppose him, John Paul “created more instant saints than all his predecessors combined.” In doing so, the Vatican officially surrendered itself “to the forces of showbiz, superstition and populism.”

While the profession of Devil’s advocate is now gone, its legacy lives on — ironically so — in science. Inspired by the age-old custom, the philosopher of science Karl Popper believed that it was better to argue against something even if you were actually for it, because doing so would remove your bias and reinforce the integrity of your results: the same line of reasoning that had led to the creation of the Congregatio.