During his own lifetime, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was one of the most distinguished artists in Europe. But today, many art lovers know the Italian sculptor only by name. This could be because, unlike Michelangelo or Leonardo Da Vinci, he was neither a rebel nor a trailblazer. Rather than breaking with the Renaissance traditions he inherited, Bernini embraced them and sought to piously improve upon them.

But this complacency, for lack of a better word, does not make him any less interesting. While Bernini did not make a permanent mark on the history and development of art, his work did have a lasting impact on real-world institutions, like the Roman Catholic Church. Virtually all of Bernini’s statues and tombs can still be found in Rome today, and they continue to shape the visual culture of the Christian faith.

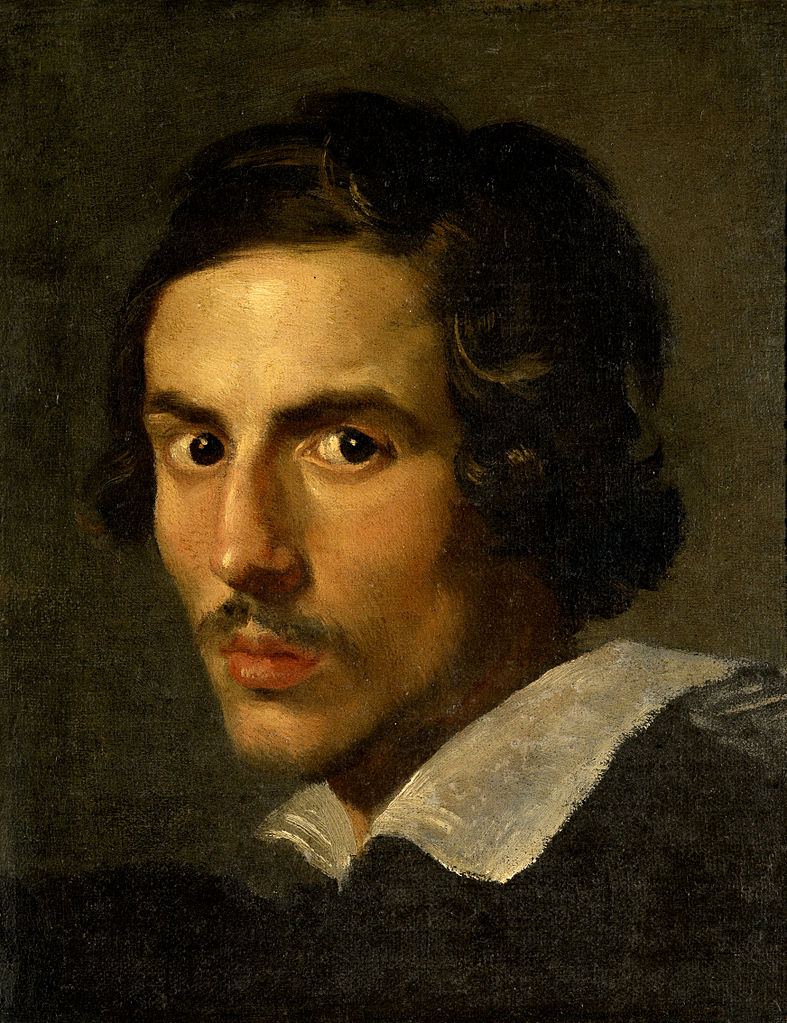

Bernini the prodigy

Bernini was born in 1598 to an accomplished but inconsequential sculptor named Pietro. Pietro’s son was a prodigy in the true sense of the word: At age 16, Bernini’s skill with a hammer and chisel not only rivaled that of a master craftsman, but his work also showed an emotional and intellectual sensitivity that ordinary children (not to mention some adults) could never possess.

Where his peers were still studying proportion and anatomy, Bernini was capable of using a single medium — marble — to convey materials with different weights and textures. He could sculpt hair being blown by the wind (Apollo and Daphne), flames rising up from a pyre (Martyrdom of St. Lawrence) and skin sagging off the bones of an old man (Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius).

Bernini preferred working from sketches rather than detailed studies. He was so confident in his abilities that he is even known to have worked on the final marble in the presence of his models. These practices give his work a liveliness or spontaneity that is often absent in sculpture, and which has allowed interest in his work to endure among modern artists in spite of his servile subject matter.

Yet Bernini was not as servile as we have been led to believe. He did in fact break with several traditions that, though they seem insignificant today, were seen as provocative by his contemporaries. For one, he frequently created sculptures that had to be looked at from a fixed angle — a departure from the Renaissance notion that statues should be admired from multiple perspectives.

He also broke with the notion that art and architecture should remain separate, with the latter being used as a space within which to encompass the former. Bernini strove to combine disciplines to create a kind of prototypical Gesamtkunstwerk, or a “synthesis of the arts.” While constructing the Cornaro Chapel, for instance, he created a hidden opening in the roof to allow natural sunlight to illuminate his religious sculptures.

Sculpting the Counter-Reformation

Bernini’s career depended not only on his skill but also his friendship with cardinal Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, who had been a generous patron of the sculptor for many years. When Barberini was elected pope of the Roman Catholic Church in 1623, he appointed Bernini as the resident artist of the Vatican and — by extension — the city of Rome.

The motivations of Barberini — then known as Urban VIII — were manifold. He appreciated fine art, spending more on commissions than any pope before or since. He also enjoyed Bernini’s company, and wanted him around as much as possible. More importantly, however, Urban VIII sought to use Bernini’s talents as an image-maker to reaffirm the authority of his institution.

That authority had been threatened during the Reformation, when reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin criticized the Church’s embrace of religious art on grounds that this art distracted people from the humble origins of their faith. As Protestant parishes banned and even destroyed artwork, the Catholic Church doubled down on its significance in a process now referred to as the Counter-Reformation.

Bernini, a devout Catholic who for the last forty years of his life went to church every day, was to become one of the Counter-Reformation’s foremost architects. His sculptures not only expanded the Church’s visual culture, but also sought to reframe fine art as a means through which to connect with God. His sculpture, Ecstasy of St. Teresa — placed in the Cornaro Chapel — is a great example of this.

According to Bernini biographer Howard Hibbard, the sculpture was “an exercise of devotion, an opportunity to enlighten and inspire. [Bernini] took Teresa’s text in the spirit in which it was written and made the hallucinatory event appear as real and concrete as possible.” In doing so the artist managed to create “an image that can serve as a means to inspire religious communion.”

Bernini’s conception of religious art was inspired by the writings of Catholic saints. St. Ignatius’ book, Spiritual Reflections, widely read among nuns like Benedetta Carlini, taught people how to use their imagination to reconstruct scenes from prayers and sermons. Teresa of Avila herself, meanwhile, recommended the soul to “picture itself in the presence of Christ.”

Art as diplomacy

Bernini felt that sculpture was an especially useful medium through which to manifest religious abstractions. “Sculpture,” Hibbard recounts one of Bernini’s many lectures to other artists, “is a truth; a blind man can judge it. Painting is a trick, a lie, and the work of the devil; sculpture is the work of God who was himself a sculptor, having made man of earth.”

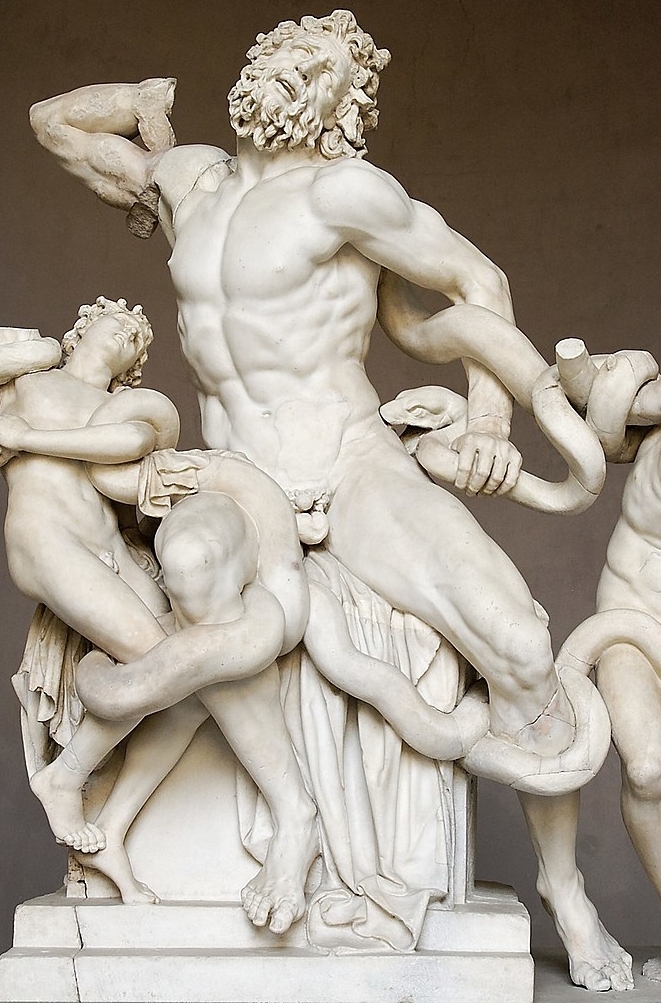

He reinforced the authority of the papacy in other, subtler ways as well. During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church emerged as both the spiritual and political successor of the Roman Empire, a connection Bernini emphasized through his art. In true Renaissance fashion, he used Hellenistic sculptures as inspiration for Christian subjects.

The Daniel, which Bernini created for the Chigi Chapel of the Santa Maria del Popolo between 1655 and 1661, is a great example of this. The twisting gesture of Daniel — the Jewish prophet who Darius the Mede famously threw into a den of lions — is clearly copied from the Laocoön and His Sons, an ancient sculpture that was excavated in Rome in 1506.

While the Christian and ancient worlds had radically different assumptions about the universe and man’s place in it, Bernini refused to separate them. On a trip to meet the court of the Sun King Louis XIV, Bernini told the French collector Paul Fréart de Chantelou that divinity hid within Greek statues, which — like the body of Adam — were made by God after his own image.

Speaking of that trip, Bernini’s art also helped Urban VIII maintain diplomatic relations with other European powers. In 1635, the pope commissioned Bernini to create a marble bust of King Charles I of England that was given to his Catholic wife and queen. The sculptor based the bust off a portrait by Flemish artist Anthony van Dyck, which was brought from England to Rome by an ambassador.

This ambassador, a wealthy Englishman by the name of Thomas Baker, was so impressed by Bernini’s talents that he commissioned a sculpture of his own. However, according to the English sculptor Nicholas Stone, Urban VIII forbade Bernini from finishing this project because he “would have no other picture sent into England from this hand but his Mai[es]ty.”

Bernini’s legacy undone

When Urban VIII died in 1644, Bernini lost his friend, patron, and protector. Urban’s successor, pope Innocent X, had different tastes, and Italian artists who had spent the previous two decades shoved to the sideline were eager to make their own mark on the Eternal City. Although Bernini still created important works for the Church, he would never regain the prestige he held under Urban.

As Bernini fell out of favor with the Vatican, so too did the Vatican lose its place as the cultural and political epicenter of the western world. An age of monarchies was dawning in France under guidance of Louis XIV, whose artistic sensibilities — while developed in their own right, according to Bernini — were rooted in a cultural heritage that was neither Italian nor Roman.

Bernini’s later work became increasingly expressive and personal, the work of a devout Christian who had become surrounded by doubt and heresy. He continued to work until his right arm was paralyzed, an unfortunate but nonetheless predictable outcome of a productive lifetime. He died at the age of 81, having served a total of eight popes.

In hindsight, Bernini was not as timeless as Michelangelo or Da Vinci. He was, however, an emblem of the time in which he lived and the cultural issues that were being debated at the time. His sculptures not only reveal the philosophy of the Counter-Reformation, but also betray the inevitable end of the Roman Catholic Church’s centuries-long reign over Europe.

Bernini’s originality lies in the unusual application of his genius. “Unlike previous religious art,” concludes Hibbard’s book, “which told stories or illuminated divine events and emotions, Bernini’s point of reference was the human worshipper; his goal was the revelation of divinity to the common man through empathy and analogy, and in this realm, he stands alone in the history of art.”