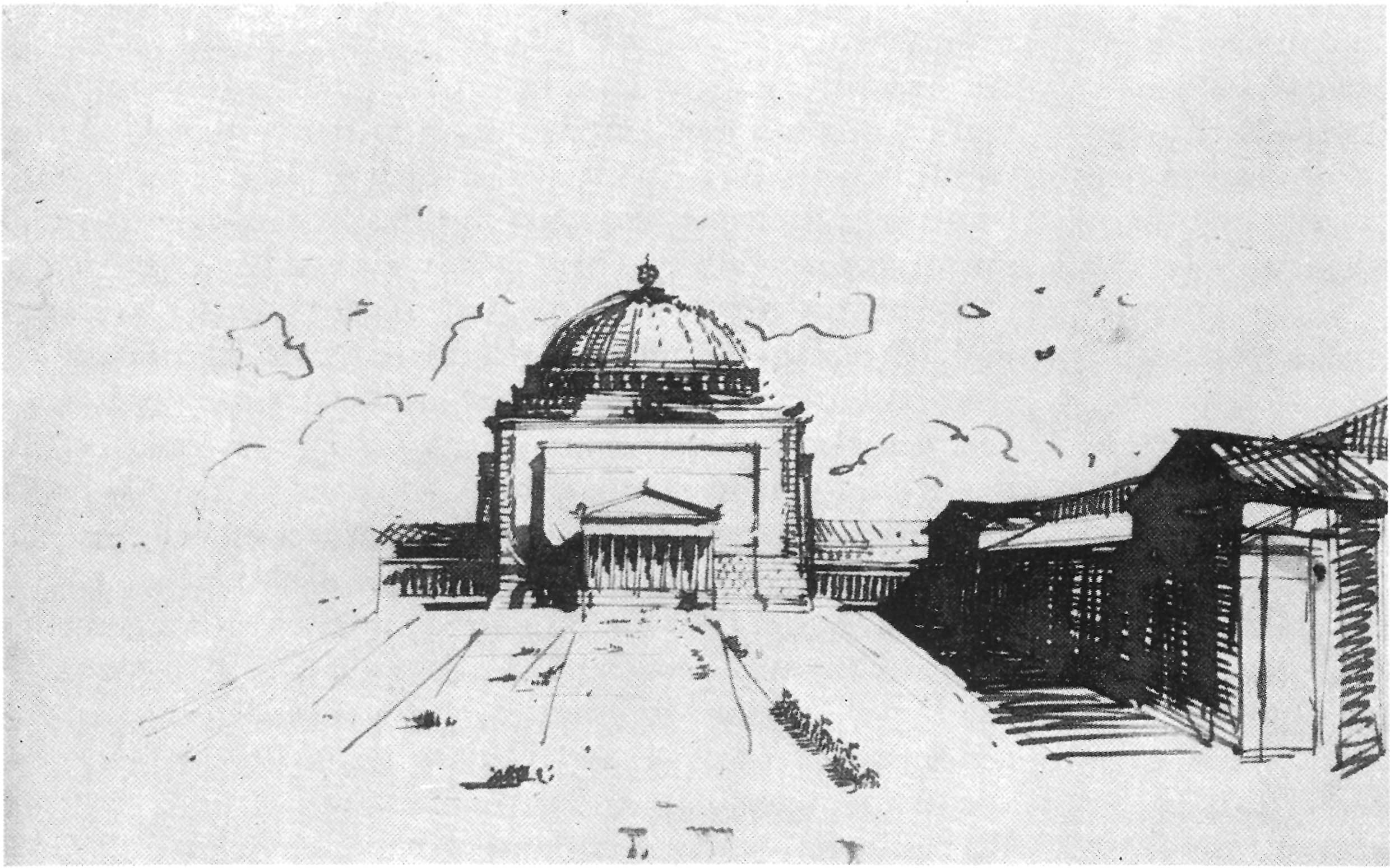

Étienne-Louis Boullée was a French architect from the 18th century who is remembered most for buildings that were never built.

Boullée began his career designing country homes around Paris. A member of the Académie Royale d’Architecture who earned the bulk of his living as a professor of architecture rather than as a practicing architect, he was able to work on blueprints without having to worry about things like money and resources. Limited only by his own imagination, he drew up plans for buildings of impossible scale.

But Boullée’s designs were never big just for the sake of it; immense size always served a simple aim. That aim, as YouTube’s Kings and Things explains in a video about his work, “was to create buildings that would instinctively make us feel in a way that corresponded to their nature or purpose.”

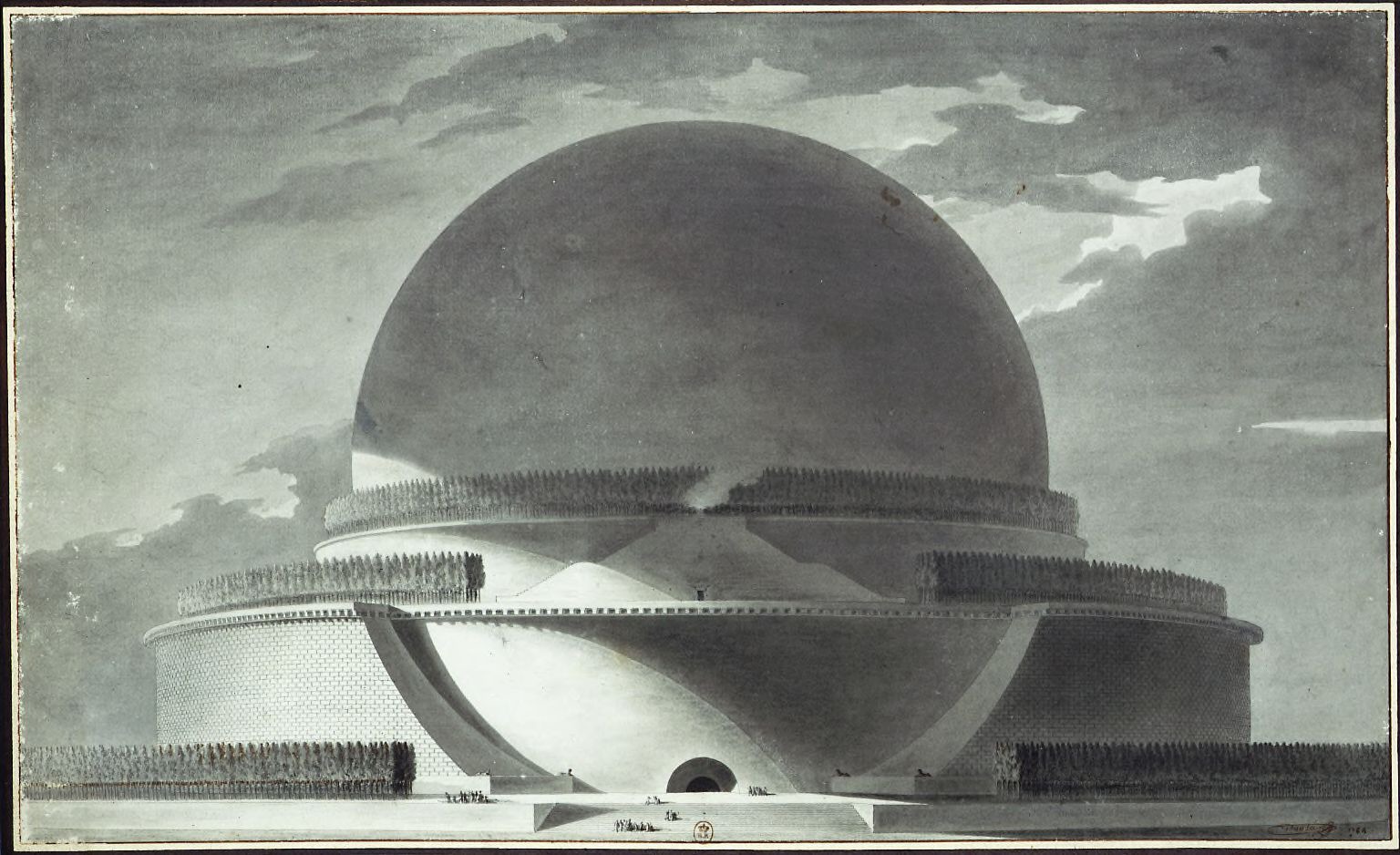

For example, city walls had to be enormous in order to intimidate invaders on the outside and secure the citizens on the inside. He imagined courthouses and government offices to be built atop relatively small jails to symbolize criminality being crushed under the weight of justice. His plans for a tomb for Isaac Newton, who discovered the laws of gravity, featured a 500-foot sphere with holes in the exterior so that, in daylight, the interior of the building would give the impression of a complete night sky.

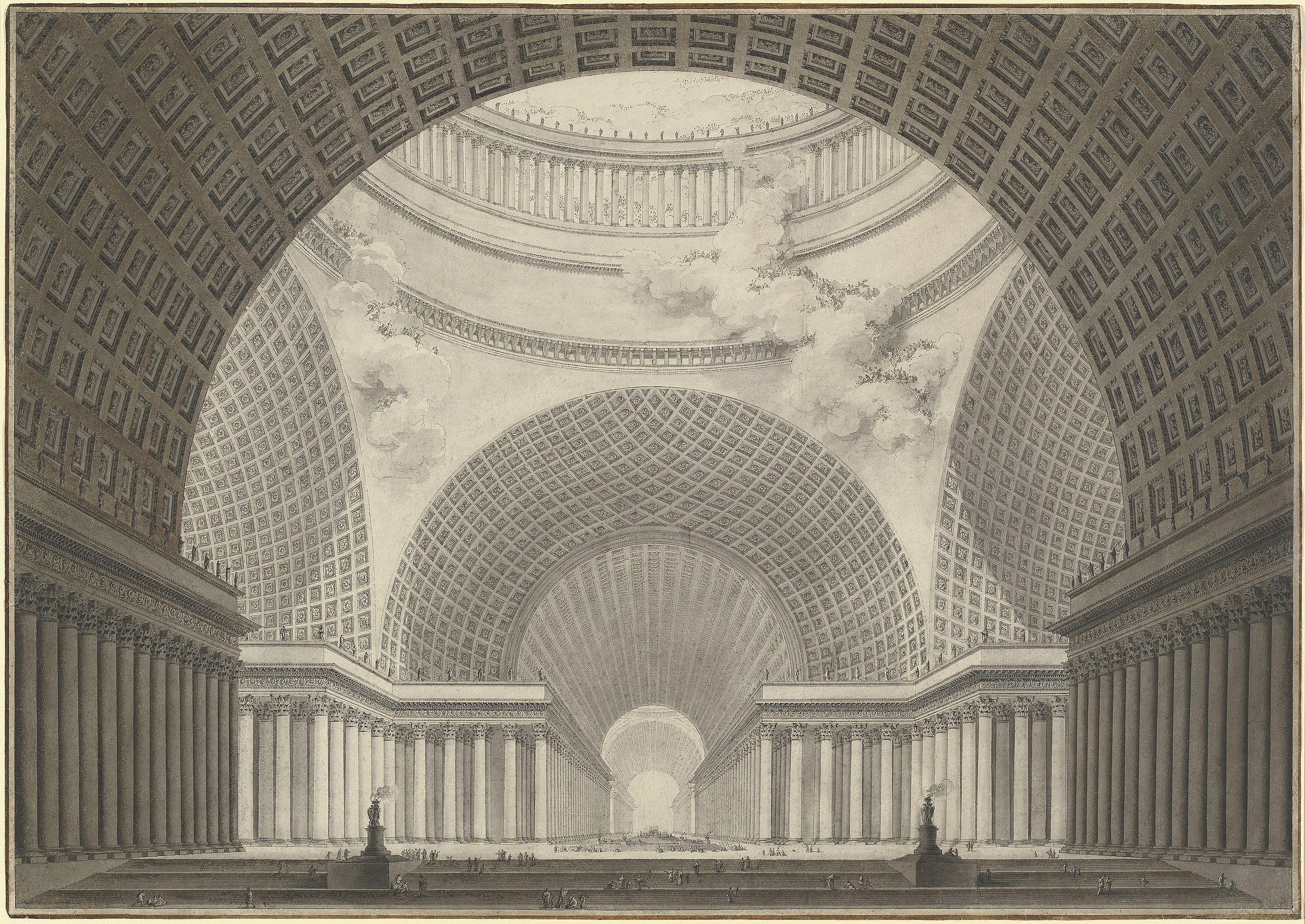

He also designed a Parisian colosseum with a capacity of 300,000 people, half the city’s total population at the time and twice as large as the largest stadium in use today. His reasoning? A construction used for public spectacles should be able to welcome as many members of the public as possible.

Boullée’s ideas about the art of architecture are best encapsulated by his blueprints for places of worship, which he felt had to inspire humility, reverence, and obedience through their appearance.

“Since man is always impressed by size,” he wrote in an essay, “it is certain that a Temple built in honour of the Divinity should always be immense. Such a temple must be the most striking and the largest image of all that exists: it should, if that were possible, appear to be the universe.” In theory, he concluded, any architect who allowed their designs to be compromised by lack of space or funding would fail to do their subject justice.

Symbols of power

Boullée never intended for his architecture to be constructed, but he inspired plenty of architects who were fully intent on turning their own improbable blueprints into reality. We discussed Vladimir Tatlin, creator of Tatlin’s Tower, in a previous article. But there was another, even larger communist monument, that actually entered the first stages of assembly: the Palace of the Soviets.

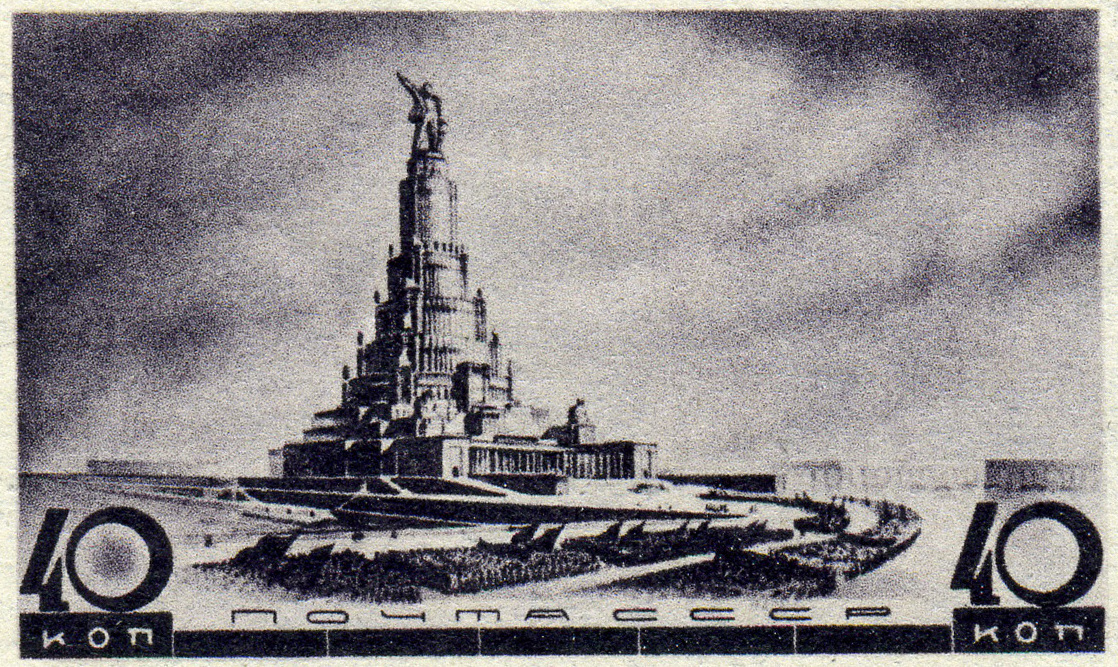

The Palace of the Soviets would have housed the governing body of the Soviet Union, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, in a grand hall measuring 430 x 330 feet (131 x 100 m) with a capacity of 20,000 people. The grand hall would have been topped by a 1,365-foot (416-m) tower, which itself would have been topped by a 300-foot (91-m) statue of the Soviet Union’s founder, Vladimir Lenin. The complex, which would have been built on the site of Russia’s biggest church, Christ the Savior Cathedral, was the brainchild of architect Boris Iofan, whose classical design beat out the more avant-garde submissions of his competitors.

Iofan’s victory, historian Sona Stephan Hoisington writes in an article, was indicative of a shift from “modern and functional architecture toward architecture that is eclectic and monumental,” qualities shared by other gigantic Soviet structures like the Worker and Kolkhoz Woman statue.

Like Boullée, Soviet architects wanted to build large buildings for a reason: to display the power and ingenuity of the regime they served. The Palace of the Soviets would have been several orders of magnitude larger than Christ the Savior Cathedral — a not-so-subtle metaphor for how the current communist society had replaced the old, religious one. It also would have been taller than any skyscraper in the United States, serving as proof that Soviet builders were superior to their capitalist counterparts.

The even bigger Volkshalle of Nazi Germany followed the same design philosophy. Based on the Pantheon in Rome, the structure would have been capped by a dome so large that the entirety of St. Peter’s Cathedral could have lowered through it. It was also claimed that the condensed breath of congregating Nazis would have formed indoor rainclouds. Just as the Palace of the Soviets was envisioned as a monument to Lenin in the center of a reconstructed Moscow, so the Volkshalle — German for “The People’s Hall” — would have commemorated Adolf Hitler at the heart of a renewed Berlin.

From skyscrapers to “skypenetrators”

American architects generally have been more interested in constructing tall buildings than big ones. This is in part because allocating the massive amounts of material and manpower necessary to construct something the size of the Palace of the Soviets is much easier in a planned economy than it is in a market-driven one. Tall buildings like skyscrapers have less volume and make better use of space, which is why they began to pop up everywhere in U.S. cities as soon as the technology to build them became available.

Skyscrapers were built in quick succession, each one taller than the last. The 630-foot (192-m) Singer Building in New York was the tallest in the world upon its completion in 1908. However, the building only held this title for a year, being overtaken by the Metropolitan Life Tower in 1909. In the next few decades, the title passed to the Woolworth Building (791 ft, or 241 m), followed by 40 Wall Street (928 ft, or 283 m), the Chrysler Building (1,046 ft, or 319 m), and the Empire State Building (1,250 ft, or 381 m).

The taller skyscrapers get, the more complicated and expensive their construction becomes. Because of this, records are broken less frequently today than they were in the past. The 2,722-foot (830-m) Burj Khalifa, which has held the title of the world’s tallest piece of architecture ever since its opening in 2010, is unlikely to become surpassed in the near future.

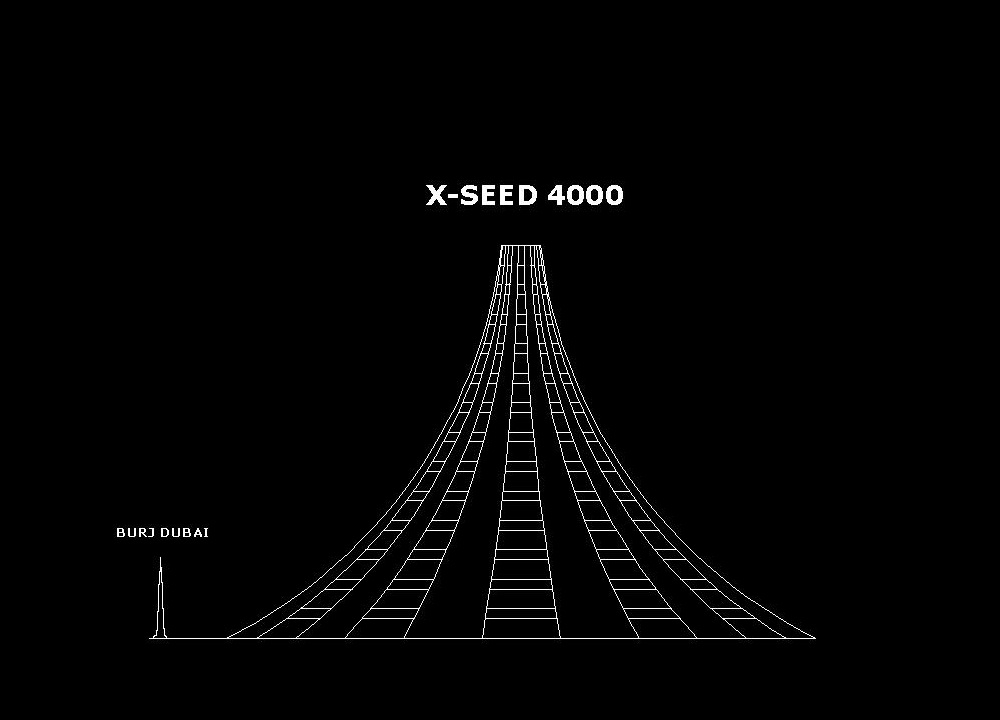

As the public wonders if skyscrapers have reached a size limit, engineers are trying to come up with ways to climb higher. The Illinois, a one-mile (1.6-km) tower proposed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1956, would have been considerably taller than the tallest building ever built at the time (or even today). To prevent his creation from falling over, Wright planned on burying the base 150 feet into the ground and using tuned mass dampers to reduce vibrations. Mass dampers remain in use today, but most architects prefer to broaden their bases rather than bury them. Consequently, plans for the next generation of mega-tall skyscrapers — also referred to as “skypenetrators” — look more like the Eiffel Tower than the Empire State Building.

William Baker, a structural engineer who worked on the Burj Khalifa, says the potential size limit for architecture is much higher than most of us think. His measuring stick isn’t the Burj but Mount Everest, the tallest thing in the world. “Buildings are far lighter than solid mountains,” he told Bloomberg in 2012. “A building could, hypothetically, climb to nearly 59,000 meters without outweighing Mount Everest or crushing the very earth below.”