Artist Agnieszka Pilat’s strange journey from communist Poland to capitalist San Francisco

- Agnieszka Pilat is a contemporary artist born in Poland who launched her career in San Francisco.

- Though classically trained to paint people, Pilat now uses her skills to create portraits of celebrity robots.

- In a time where many people are pessimistic about the potential and application of technology, Pilat remains unapologetically futurist.

Agnieszka Pilat is a contemporary artist whose success story can be broken up into the following chapters: After studying painting and illustration at the Academy of Art University, where she was classically trained, she spent years painting portraits in a small studio located somewhere in San Francisco. While her paintings were impressive on a technical level, they failed to capture the attention of the Bay Area’s increasingly competitive art scene, which favored abstraction.

Then, by chance, Pilat ran into a certain someone named Paul Stein. Stein is a developer who is credited with building the headquarters of Airbnb. He is also a collector, not just of art but also of eye-catching objects salvaged from previous projects. One day, Stein invited Pilat to his office to paint an object of her choosing. After careful consideration Pilat settled on a vintage fire alarm bell, which she painted with the same care and precision as she would a human sitter.

This unsuspecting assignment proved to be the breakthrough that Pilat had been hoping for. Curiosity about her work spread through word of mouth, not among gallery owners but the tech executives of nearby Silicon Valley. Soon enough, Pilat was receiving commissions from the likes of Peter Hirshberg, the chairman of blockchain company Swytch.io, and Steve Jurvetson, a venture capitalist who served on the board of directors of both Tesla and SpaceX.

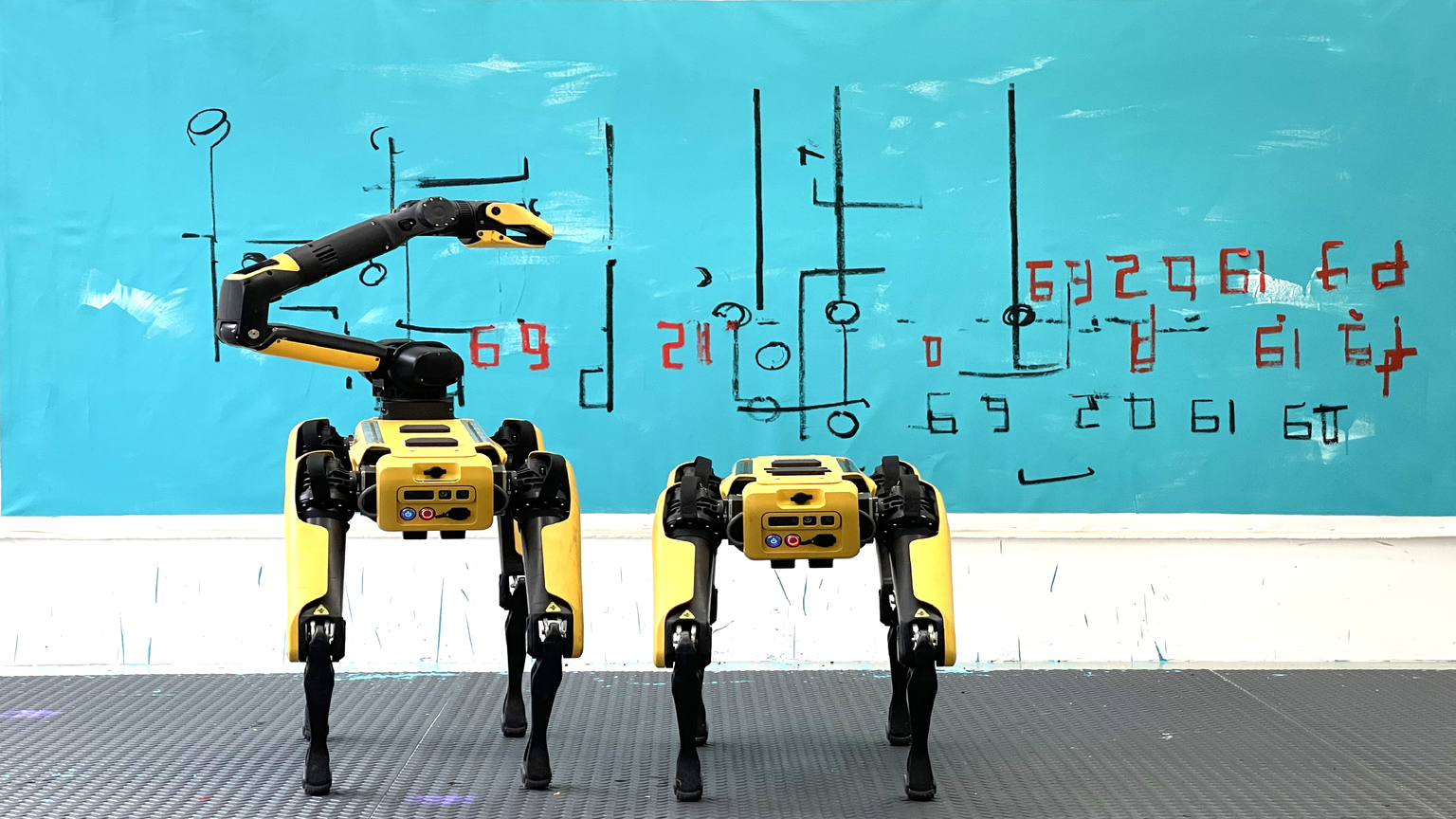

By this time, Pilat had given up on painting humans and was focusing exclusively on painting machines. She traveled east to meet the engineers at Boston Dynamics, who in her opinion had created the first “celebrity industrial robot” in the form of Spot. Spot is a four-legged robot that can traverse difficult terrain, inspect hazardous materials, or fetch you a drink. It has become instantly recognizable thanks to social media and, according to Pilat, was due for its own portrait.

Pilat is now one of the most commercially successful artists in America. But despite (or perhaps because of) her success, her work has been ignored by critics, who claim she is merely pandering to the poor tastes of society’s upper echelon and Silicon Valley. This is unfair because — like any other important artist before her — Pilat’s work tries to connect opposing forces: man and machine, art and artificial intelligence, and (last but not least) communism and capitalism.

From Poland to San Francisco

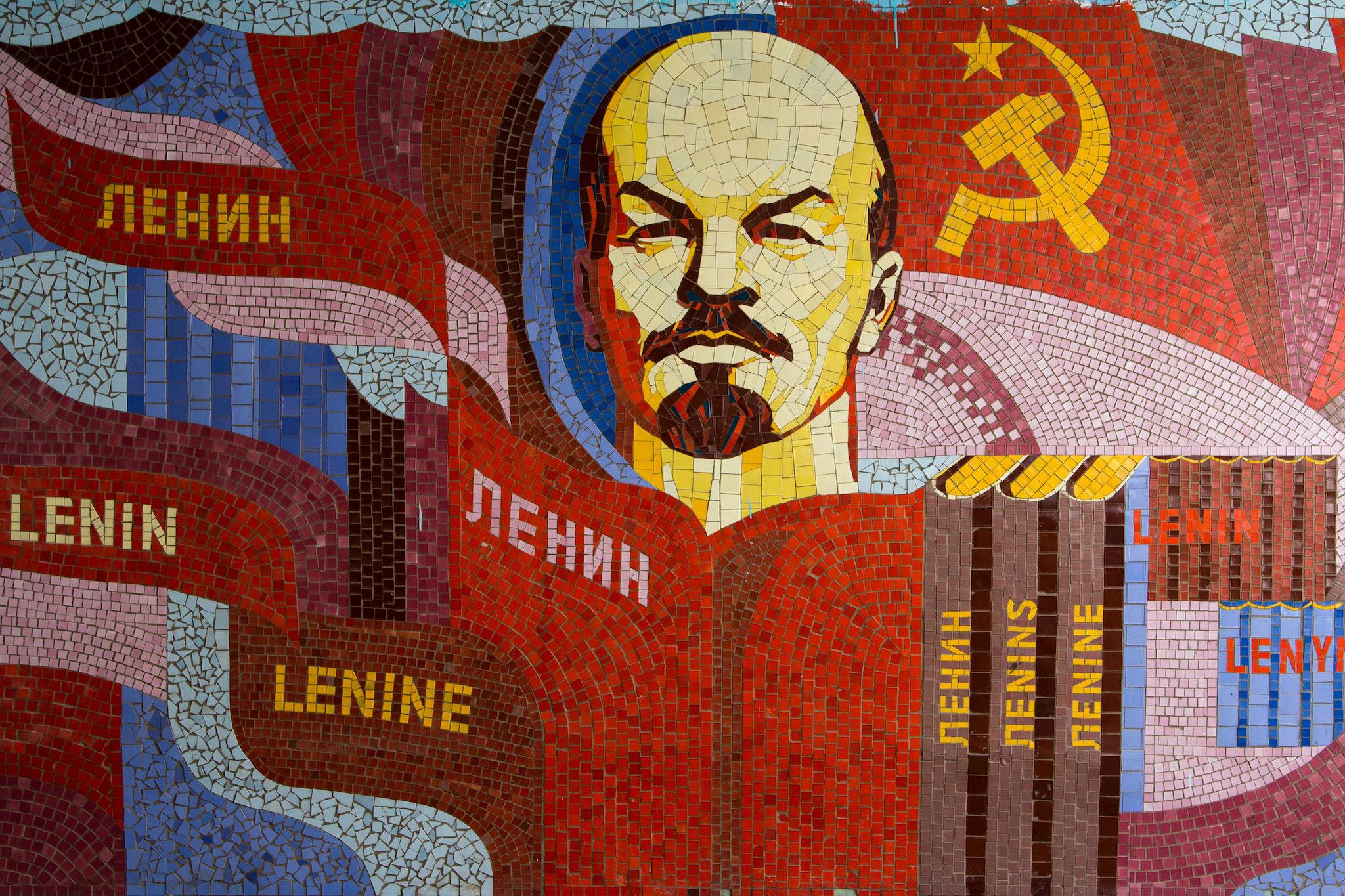

Nobody appreciates freedom more than those who have been deprived of it. Pilat was born and raised in Poland, back when it was under the thumb of the USSR. When asked to describe this period of her life, she uses the word “Kafkaesque.” Family vacations, for instance, were set up by the government. Before you traveled to your assigned destination, you had to show up at the local police station to tell them where you were going and how long you’d be gone for.

Private businesses were outlawed and every transaction had to be registered by the state. This included livestock, which went for such low prices that farmers often sold under the table just to make a bit of extra cash. Pilat remembers her parents driving into the country to buy a pig for her uncle only to be pulled over by the cops and searched for farm animals in much the same way American teenagers get searched for marijuana.

During her youth, Pilat idolized the United States: a land of civil liberties and a free market economy. However, when she finally emigrated and settled in San Francisco, she was bitterly disappointed. Pilat expected a city that was decidedly Western not just in appearance but also in mindset, only to find a highly regulated environment full of political and cultural red tape. Worst of all was the general distrust toward wealth and affluence.

Pilat had trouble understanding this distrust. Where she was from, everyone from janitors to brain surgeons earned the same wage — a policy that, in her words, created a world in which “jealousy and envy simply did not exist.” On top of this, she also came from a family that found success not through privilege but hard work; once the Polish government began allowing citizens to own and operate private businesses, her father, a pastry chef, worked to lift the Pilats out of poverty.

In recent years, Pilat’s worldview has been influenced heavily by Ayn Rand, a Russian-American philosopher and writer who championed laissez-faire capitalism while rejecting both altruism and collectivism on grounds that they prevented people from developing their individual talents to the fullest. Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged is a favorite of Pilat. Coincidentally, the book has also rested on the nightstand of many a Silicon Valley tech mogul.

The souls of machines

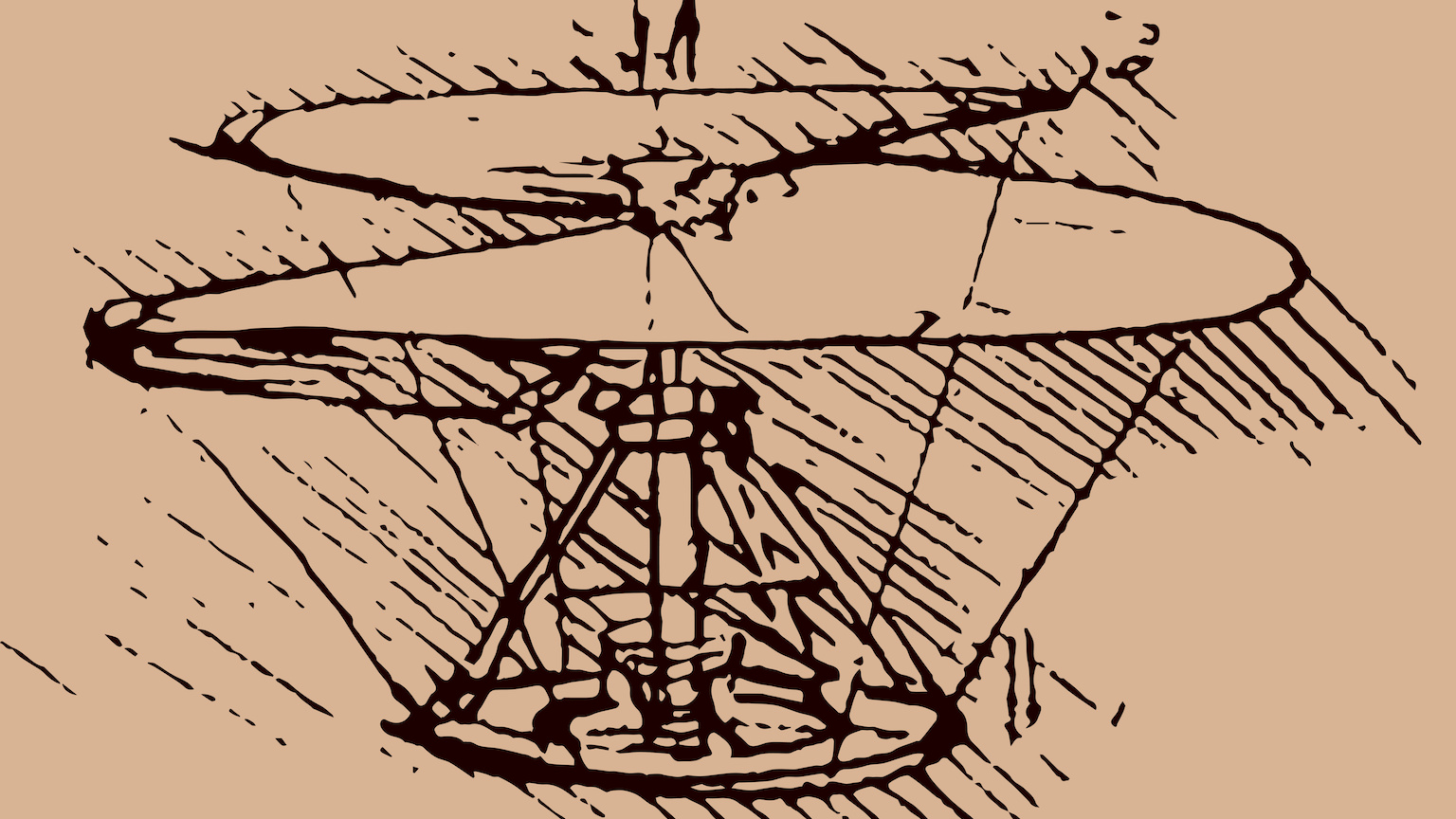

Pilat’s patrons not only like her work because they share the same ideas about commerce and individuality, but also because she, like them, sees technology in a positive light. This light shone brightly during one of her latest exhibits, Renaissance 2.0, which an article from Wired described as “a reflection of the parallels between the Italian Renaissance” and “a global technological renaissance with roots in Silicon Valley.”

The exhibition included parodies of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel, but with the humans replaced by Spot and Atlas, another robot created by Boston Dynamics. The paintings are collaborations between man and machine; Spot has a mechanical arm that can wield a paint brush, and its broad, patched strokes add a level of abstraction to Pilat’s which she always felt was lacking.

Critics remain suspicious of her paintings, which Intelligencer journalist Shawn McCreesh once said were “in service to the tech nomenklatura at a time when much of the country has come to despise its members for the forces they have unleashed on society and for their obscene levels of wealth.” Pilat would beg to differ. Having grown up in a communist country, she’s intimately familiar with propaganda art and claims to serve no one except her own beliefs.

In this regard, her work speaks louder than her words. When her career as a portrait painter of machines was well under way, she was approached by Waymo to paint the Lidar component of the Silicon Valley company’s fabled self-driving cars. After several months of trial and error, Pilat gave up on the project because she felt she was unable to “capture the soul” of the technology. It’s a problem she used to encounter quite often, but one she finally solved while painting Spot.

New forms of technology she discovered, are like children and should be painted accordingly. In order to pull off a convincing portrait of either subject there has to be, as Andy Warhol showed in his portraits, an element of playfulness. Pilat started painting her portraits of Spot using bright, pastel colors like baby blue and pink. “When you paint a baby,” she tells Big Think, “it’s difficult because there is nothing there. Conceptually, this technology is in an embryonic stage.”

The futurism of Agnieszka Pilat

More interesting than Pilat’s work is its context within the art world and society at large. Her optimistic interpretation of machines like Spot and the engineers that design them could not be more different from the dystopian not-so-distant-future we are presented with in the Netflix show Black Mirror. In the episode “Metalhead,” robotic dogs similar to those designed by the company are cast as antagonists hunting down people in a post-apocalyptic world.

Black Mirror wasn’t the first artistic production to cause Boston Dynamics’ PR department a headache, nor was it the last. Last year, an American art collective held an exhibit where people could take control of a paintball gun mounted on Spot’s back and use it to destroy an art gallery. The engineers released a statement saying they “condemn the portrayal of our technology in any way that promotes violence, harm or intimidation.”

Pilat’s work celebrates the kind of innovation that, for better or worse, is being driven by experts in service of Silicon Valley. It is a controversial stance to take in today’s political climate. From an artistic perspective, though, it’s also reminiscent of the sort of controversy Marcel Duchamp whipped up when, in 1917, he made the bold though ultimately correct supposition that a urinal signed “R. Mutt” could be considered high art.

Ironically, Pilat’s work also echoes the prolific but ultimately disgraced art movements that helped establish and inform the Soviet Union. These movements included artists like the Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov, whose 1924 manifesto posited the camera as a superior version of the naked eye. Vertov’s early documentary reels, like Pilat’s paintings, depict machines as autonomous and intrinsically valuable entities, rather than tools in service of their creators.

While Pilat’s critics are correct in saying her work embodies the enthusiasm for and faith in technology that helped make Silicon Valley into what it is today, they are wrong to believe this attitude is somehow misguided. Art can deconstruct the human experience, but technology can reconstruct it. Art allows us to understand real-world problems, but technology enables us to solve them. “Art,” Pilat adds, “is great, but technology is holy.”