When you lose weight, where does the fat go?

Fat has made a comeback of late. Of course, the fat on everyone’s mind is dietary fat, those nine calories per gram advocated by fans of the ketogenic diet. The fat we carry around inside of our bodies is a different story.

Not that fat hasn’t previously been in vogue. Carrying around a little extra was once considered a sign of wealth—those pounds meant you could afford to eat well. Humans being humans, we then took it to the other extreme when the fashion world became fascinated with anorexic models. As they infiltrated popular culture, eating disorders, depression, and anxiety ravaged our consciousness. We still haven’t self-corrected from that swerve.

The connection between wealth and fat is not surprising. Storing excess money in your bank account is a sign of financial success; your body stores fats and carbohydrates so that you never run out of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecules that serve as batteries in your body’s cells. Your body’s account needs ATP in case a debit becomes necessary.

Good fat and bad fat

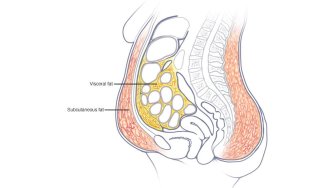

What we’re looking for at a healthy weight is proper energy balance—enough stored energy for when you need it, not so much that it collects in the form of visceral fat, mostly around your belly. Too little stored fat and you run into reproductive problems, which is why our bodies are good at storing fat. Too much, our main problem today, and we suffer the long list of metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune issues clogging hospital corridors.

Fat, remember, is necessary for good health. Your body stores some fat cells in your liver and some in your muscles. A lot of them are used for resting metabolic processes—around 1,300 to 1,600 calories worth daily. The remainder is spread throughout your body in the form of adipocytes; each of us carries around tens of billions of these fat cells.

The cells stored beneath your skin are subcutaneous fat, which we need. Visceral fat is the problem, as these cells act differently in your body. When visceral fat collects around your midsection, the excess energy is also collecting a variety of vitamins, hormones, and toxins, the latter in an attempt to keep them away from your organs. This might seem positive, but in the long run this storage of pollutants and toxins can be, well, toxic, especially if you lose weight too quickly.

Image source: Mayo Clinic.

Where does the fat go?

Where do you lose weight in the first place? Mostly, through breathing. While the concept of “burning” fat is not altogether wrong, losing fat involves plenty of carbon dioxide leaving your body. As the Washington Post explains:

[Researchers] found that to burn a pound of fat, a human needs to inhale about three pounds of oxygen, kickstarting metabolic processes that produce just under three pounds of carbon dioxide (which is just a bit more than the average weight exhaled by a human on any given day) and about a pound of water. That water can exit the body in plenty of ways—poop, pee, sweat, saliva and any number of bodily fluids—but your lungs handle the brunt of the weight loss.

Your fat “goes” into the atmosphere. (And no, it doesn’t contribute to global warming.) When it does go, you’re also releasing the extra storage of vitamins and toxins along with it. That might not sound like a good thing, but in the long run it’s far better to be rid of them.

As Popular Sciencestates, organochlorine pesticides, among other pollutants, are known to get bound up in fat—they leak into our food supply:

Bodies don’t seem to store enough of these to become toxic, but the constant build-up leaves you vulnerable to exposure. And they do start to re-emerge when you lose weight.

By losing weight at a healthy pace (1-2 pounds a week), the limited number of pollutants released will not overload your bloodstream. Your urine will make quick work of them. Extreme dieting is a different story. The more weight you lose, the more of these toxins (as well as vitamins and, in women, estrogen; excessive vitamins can be deadly, while increased estrogen stored in fat increases your chances of breast cancer) enter your bloodstream.

Since we no longer face the same problem as our ancestors—most of us don’t have to worry about whether or not we’ll eat tonight, or tomorrow—fat storage plays a different role in our bodies than previously. Many avoidable health problems are due to this excessive storage of energy, hormones and toxins. Some researchers claim 70 percent of our medical problems can be addressed through a healthier lifestyle, which includes eating better and moving more.

As a bonus, the fat being returned into the atmosphere through breathing eventually becomes fuel for plants, one of the main foods we want to put back inside of our bodies. That’s what we call a harmonious cycle, one we evolved because of, and one that remains necessary for optimal health today.

—

Derek Beres is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles, he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.