Baby’s first poop predicts risk of allergies

- A new study finds that the contents of an infants' first stool, known as meconium, can predict if they'll develop allergies with a high degree of accuracy.

- A metabolically diverse meconium, which indicates the initial food source for the gut microbiota, is associated with fewer allergies.

- The research hints at possible early interventions to prevent or treat allergies just after birth.

The prevalence of allergies arising in childhood has increased over the last 50 years, with 30 percent of the human population now having some kind of atopic disease such as eczema, food allergies, or asthma. The cause of this increase is still subject to debate, though it has been associated with a number of factors, including changes to the gut microbiomes of infants.

A new study by Canadian researchers published in Cell Reports Medicine may shed further light on how these allergies develop in children by examining the contents of their first diaper.

The things you do for science

The research team examined the first stool of 100 infants from the CHILD Cohort Study. The first stool of an infant is a thick, green, horrid-looking substance called meconium. It consists of various things that the infant ingests during the second half of gestation. Additionally, it provides not only a snapshot of what the infant was exposed to during that time, but it also reveals what the food sources will be for the initial gut bacteria that colonize the baby’s digestive tract.

The content of the meconium was examined and found to contain such varied elements as amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, and myriad other substances.

The authors fed this information into an algorithm that used this data, along with the identities of the bacteria present as well as the baby’s overall health, to predict which infants would go on to develop allergies within one year. The algorithm got it right 76 percent of the time.

A way to prevent childhood allergies?

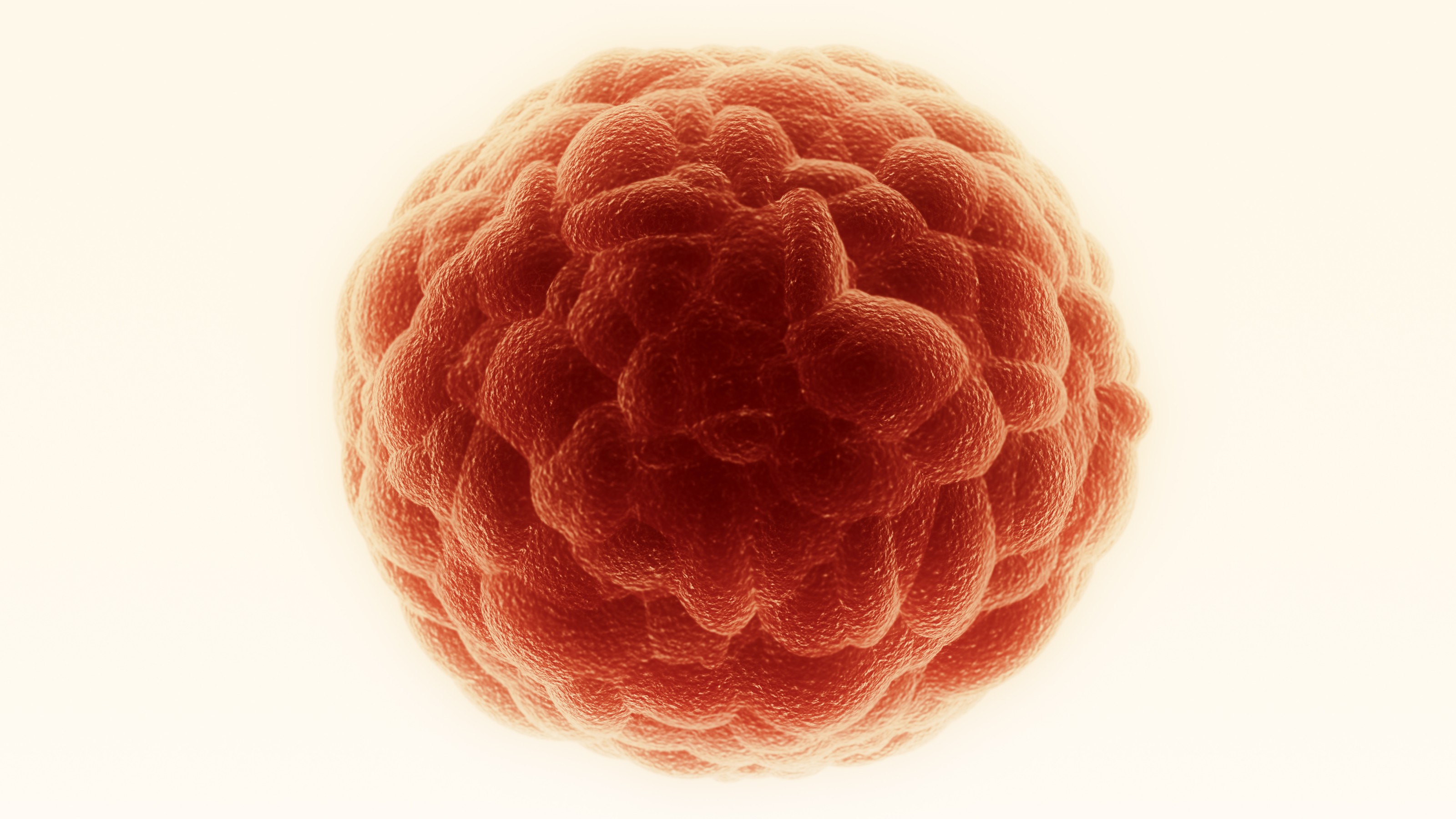

Infants whose meconium had a less diverse metabolic niche the initial microbes to settle in the gut were at the highest risk of developing allergies a year later. Many of these elements were associated with the presence or absence of different bacterial groups in the digestive system of the child, which play an increasingly appreciated role in our overall health and development. The findings were summarized by senior co-author Dr. Brett Finlay:

“Our analysis revealed that newborns who developed allergic sensitization by one year of age had significantly less ‘rich’ meconium at birth, compared to those who didn’t develop allergic sensitization.”

The findings could be used to help understand how allergies form and even how to prevent them. Co-author Dr. Stuart Turvey commented on this possibility:

“We know that children with allergies are at the highest risk of also developing asthma. Now we have an opportunity to identify at-risk infants who could benefit from early interventions before they even begin to show signs and symptoms of allergies or asthma later in life.”

A model for early childhood allergies

As shown above, the authors constructed a model of how they believe metabolites and bacterial diversity help prevent allergies. Increased diversity of metabolic products in the meconium encourage the development of “healthy” families of bacteria, like Peptostreptococcaceae, which in turn promote the development of a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. Ultimately, such diversity decreases the likelihood that a child will develop allergies.