Are “green” cleaners really less toxic than traditional products?

- Household consumer products (HCPs)—such as laundry detergents, all-purpose cleaners, insecticides, and toothpaste—are often marketed as “green” products, suggesting they are less damaging to the environment.

- However, due to proprietary considerations, HCPs do not need to disclose their individual compounds, meaning that the environmental impacts of their use and disposal remain largely unknown.

- A recent study found that green HCPs are not necessarily less toxic or more degradable than their conventional counterparts.

Modern consumers are in a pickle: We don’t want marble countertops covered in germs or our tuxedos covered in wine stains, but we also don’t want to use harsh chemicals that harm the environment. Fortunately, many companies have provided us with a solution: “green” cleaning products. From detergents to all-purpose cleaners, these items are easy to find in your local grocery store, often coming in plastic bottles covered in messages advertising “plant-based biodegradable cleaning ingredients” that are “safe for family and environment.”

However, new research published in Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry demonstrates that green products are not necessarily less toxic or more degradable than their conventional counterparts.

12 principles of “green chemistry“

Household consumer products (HCPs) are a diverse group of commercially available formulations for various home and personal uses (e.g., laundry detergents, dish detergents and gels, toothpaste and mouthwash, insecticides, all-purpose cleaners, etc.). Unlike other consumer products, such as pharmaceuticals, HCPs have not received as much attention regarding their potential environmental impacts. Also unlike pharmaceuticals, HCPs are typically not ingested by humans. As such, they do not undergo metabolic degradation before being released into the environment, meaning that large quantities of HCPs, especially cleaning products, enter the aquatic environment largely unaltered. Previous studies have shown that compounds in HCPs cause various health problems, such as infertility and developmental abnormalities.

To reduce the environmental impacts of HCPs (and pollutants in general), the EPA published a set of principles to guide the practice of “green chemistry,” an area of chemistry and chemical engineering focused on the design of products. The principles aim to eliminate the use of hazardous substances during chemical production. These principles included radical ideas such as “don’t synthesize chemicals that are toxic to living organisms” and “if you do make toxic chemicals, design them breakdown into nontoxic chemicals at the end of their designed functionality.”

As the public became more interested in environmental protection, companies began to pay more attention to these principles. So, they began marketing “green” product formulations as an alternative to conventional formulations. But due to proprietary considerations, HCPs do not need to disclose their individual compounds, meaning that the environmental impacts of their use and disposal remain largely unknown.

A small group of scientists at The Citadel, a public senior military college, aimed to determine whether green HCPs are less toxic following natural degradation processes. Based on labeling claims and the tenants of green chemistry, they hypothesized that green HCPs are less toxic than their conventional counterparts before and after degradation. However, that hypothesis was wrong.

Microbes and sunlight: nature’s two degraders

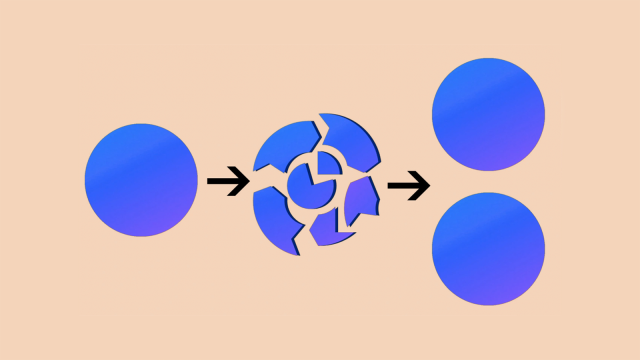

The researchers assessed two types of degradation: biodegradation and photodegradation. Biodegradation involves using microorganisms to break down biodegradable organic matter into carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic compounds. Photodegradation, on the other hand, relies on light to break down molecules and has been extensively shown to be an effective method of degrading pharmaceuticals and household products in surface waters.

In their assessments, the researchers recruited two commonly used aquatic test organisms: larval grass shrimp (Palaemon pugio) for the biodegradation study and juvenile freshwater cladocerans (Daphnia magna) for the photodegradation study. In each study, the researchers exposed the organisms to a green HCP or one of two conventional HCPs in six categories (laundry detergent, dish detergent, mouthwash, insecticide, dishwasher gel, and all-purpose cleaner).

The researchers withheld the products’ brand names but wrote that the products are readily available to consumers at grocery stores nationwide. They described the labels on all green products as “…clearly indicat[ing] that they were being marketed as an eco-friendly alternative. All green products had leaves, flowers, or plants on their label, and many included the terms ‘Earth’ and ‘Green’ directly in the product name. Other common claims made on green product labels included ‘ingredients derived from natural products, including essential oils and coconut-based cleaners,’ ‘contains plant-based surfactants,’ ‘plant-based biodegradable cleaning ingredients,’ and ‘safe for family and environment.”

Most green products didn’t become less toxic

Before degradation, only the green insecticide was significantly more toxic to shrimp than either conventional insecticide. Following a biodegradation treatment, none of the green product formulations became less toxic, whereas 44.4% of the conventional HCPs demonstrated decreased toxicity. For daphnids, green HCPs in three categories (dish detergent, insecticide, and all-purpose cleaner) were less toxic than both conventional products tested. Following a photodegradation treatment, two green product formulations (dish detergent and dishwasher gel) became less toxic (33.3%), whereas 87.5% of the conventional HCPs demonstrated decreased toxicity.

“Our results demonstrate that the end-product formulations of green products were not necessarily less toxic before or after degradation treatments, suggesting that consumer skepticism over manufacturer claims is justified,” the authors wrote. “Despite manufacturer claims and consumer assumptions that green HCPs are less toxic and more degradable than conventional HCPs, these results suggest this is not always the case. More work should be dedicated to understanding how these products may impact nontarget organisms in the environment.”