How child mortality fell from 40% to 3.7% in 200 years

- Just 200 years ago, 40% of children perished before the age of five. As Bill Bryson wrote, “The world before the modern era was overwhelmingly a place of tiny coffins.”

- Today, the child mortality rate is 3.7%.

- The collapse in child mortality rates is a testament to the tremendous benefits of scientific, technological, and economic progress.

“Infant mortality is such a powerful indicator because low rates are impossible to achieve without having a combination of several critical conditions that define good quality of life.”

— Vaclav Smil in Numbers Don’t Lie: 71 Things You Need to Know About the World

A world of tiny coffins

For tens of thousands of years, it was painfully difficult to keep the majority of children alive into adulthood. Travel back just 200 years, to the middle of the Industrial Revolution, and global child mortality was roughly 40%. That is, four out of every ten children perished before the age of five.

As Bill Bryson put it in his book At Home, A Short History of Private Life, “There is no doubt that children once died in great numbers and that parents had to adjust their expectations accordingly. The world before the modern era was overwhelmingly a place of tiny coffins.”

Indeed, life in the pre-industrial past was hungry, exhausting, astonishingly punishing, and an all too frequently short-lived existence, doubly so for children. Famine, malnutrition, disease, exposure, accidental injury, and violence, were largely unchecked drivers of child mortality for thousands of years.

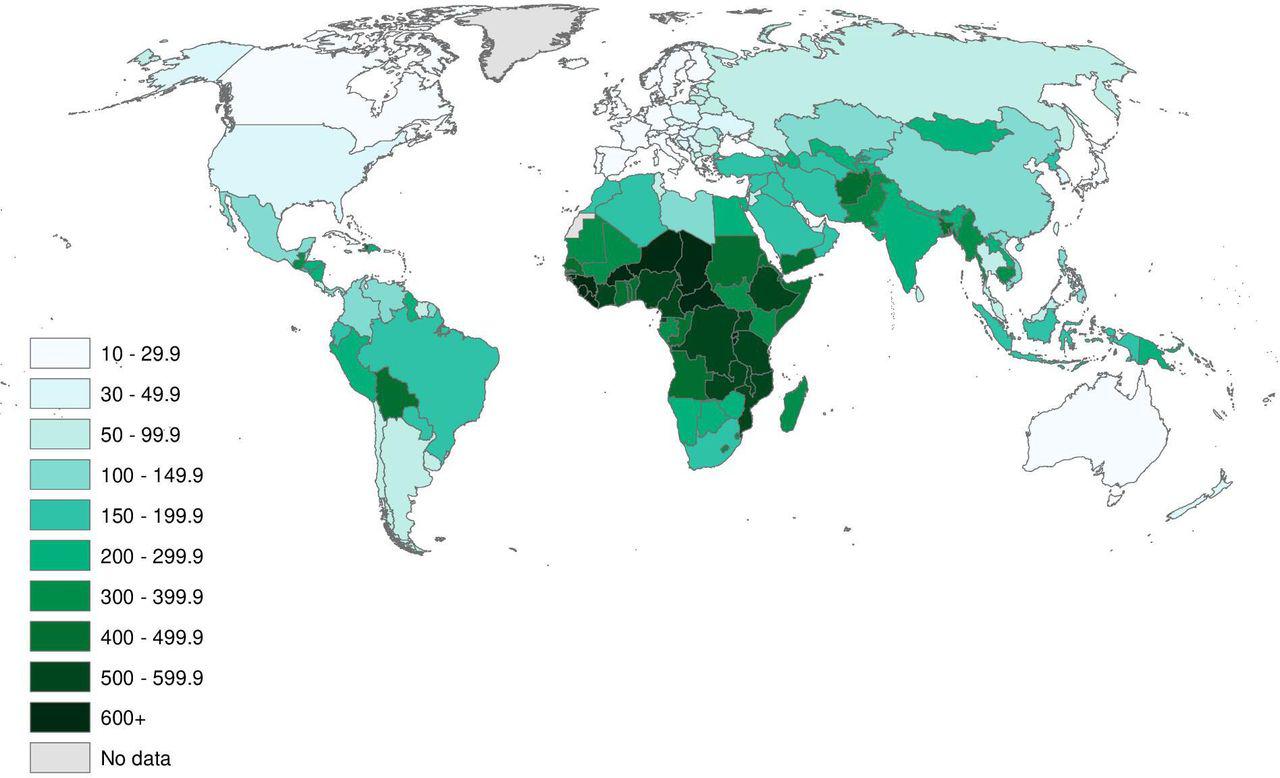

From the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, child mortality figures barely budged. In the best case scenario, a mother living in pre-industrial Europe might expect to suffer the loss of three in ten children; in the worst case scenario, more than double that. By the end of the 19th century, the best performing countries — New Zealand, Australia, Norway, and Denmark — saw 105 to 163 children under the age of five die per 1,000 live births, while the rate in China, India, and Bangladesh was 417, 536, and 565, respectively.

An historical turning point

But then, starting in the early 1900s, and for the first time in human civilization, child mortality rates began a slow but steady decline, starting first in the wealthiest countries — those with GDP per capita of $4,000 to $10,000+. In 1925, it took a GDP per capita of $8,000+ to reduce child mortality to under 10%. Progress continued through 1950, and then began to gather real pace. The globalization and economic growth that started in the post-war era kicked off the greatest transformation in child mortality in history.

The global economic growth that started in earnest in the early 1950’s provided unprecedented gains in income at the individual and government level, providing the capital to invest in the prime drivers of progress against child mortality. Increased family income provided better access to food and shelter, basic education, clean water, and cleaner heating and cooking fuels (a major contributor to mortality from indoor air pollution). At the government level, growth provided the capacity to improve clean water delivery, sanitary solid and liquid waste removal, vaccination, and access to government support for those most disadvantaged, and dramatically improved prenatal, neonatal and post-neonatal care.

As a result, child mortality rates plummeted — from 300 to 500 deaths prior to age five per 1,000 live births circa 1800 to just 37 per 1,000 in 2020. Child mortality is lower today in China, India, Egypt, Algeria, and Libya than it was in the U.S., UK, or France in 1950.

It takes an advanced village

Economic growth and sound institutions have saved the lives of tens of millions of children in the last 200 years. But there is no quick fix to child mortality, no single solution to take a country (like Thailand) from a child mortality of roughly 20% circa 1950 to 0.8% in 2020. It has been said that “it takes a village to raise a child,” but it takes a fairly advanced civilization to raise most children to adulthood.

While it took a GDP per capita of $8,000+ to achieve a child mortality of under 10% 100 years ago, today, no country on Earth with a GDP per capita of $1,500+ has a child mortality greater than 10% (with the exception of Nigeria). And that same $8,000 in GDP per capita now buys a child mortality rate of roughly 2.5%. It is simply indisputable that from Bangladesh to Belgium, and from Germany to Ghana — whether boy or girl, rich or poor — there has never, on average, been a better time to be born into the global community.

More progress needed

Progress forward is not, however, progress completed, and there remains an enormous scope of opportunity for progress in reducing preventable child mortality. The WHO remains concerned that:

“[M]any countries remain off track to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on ending the preventable deaths of newborns and children under age 5. If current trends continue, 54 countries will not meet the under-five mortality target by 2030, and 61 countries will miss the neonatal mortality target. The SDGs call for an end to preventable deaths of newborns and children under age 5, with all countries aiming to have a neonatal mortality rate of 12 or fewer deaths per 1,000 live births, and an under-five mortality rate of 25 or fewer deaths per 1,000 live births, by 2030.”

While the challenge of driving down child mortality in the developing world (for instance, 11+% in Somalia and Nigeria, and roughly 6% in Pakistan and Afghanistan) may feel insurmountable, the good news is that there are few technical or scientific challenges standing in the way. A future where Somalia and Afghanistan have child mortality rates as low as Australia (3.4%) or South Korea (2.8%) is a future that is possible.

The drivers of progress that reduced child mortality so greatly from 1950 to 2022 are still at work, as global economic growth and innovation will continue to help countries with sound institutions and governance to provide their children with the best possible future.