Scientists Dose “Mini-Brains” with a Psychedelic Drug to Understand How It Works

In the Americas, shamans in pre-Columbian societies used psychedelic substances to help cultivate wisdom, gain insights, and commune with the divine. According to new research, such substances may help in more clinical ways. They could be used to treat depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other psychiatric disorders.

Yet, little is actually known about them from a scientific standpoint. The CIA conducted experiments in the mid-20th century to find out if psychedelics could make hypnosis easier, or help a soldier better withstand “privation, torture, and coercion.”

Ken Kesey, author of the classic One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, was one such test subject. The influence of the experience helped him and others birth the counterculture movement of the 1960s, which ultimately stood against the very system that had tested them in the first place.

There was a short window in the late ’50s and early ’60s where psychedelics were used in the psychiatric community to help patients overcome certain disorders. Iconic Hollywood actor Cary Grant is known to have undergone 100 such therapy sessions.

Since the ’60s, psychedelic drugs have become taboo and highly illegal. It’s feared they cause psychosis, despite little actual data suggesting so. In recent years, a small but growing number of studies have returned to the pre-counterculture outlook—that they might help treat certain disorders. LSD, ayahuasca brew (containing DMT), and MDMA have all been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory and antidepressant properties.

Did ancient shamans of North and South America know something that science is only catching onto? DMT, sometimes called the “spirit molecule,” has been a part of shamanic traditions for hundreds of years. The chemical used in this study is a variant of DMT.

The CIA tested psychedelics on unsuspecting subjects to try and gain an edge during the Cold War. Credit: Getty Images.

So what’s the breakthrough? Brazilian researchers have identified the signaling pathways that DMT takes in order to engage neuroplasticity (or changes inside the brain). The results of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

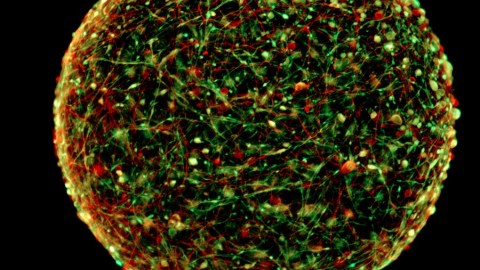

Overall, scientists try to uphold things like research ethics. Plus, it’s illegal to smoke DMT inside an fMRI machine. Or anywhere. So instead, investigators observed the effects the psychedelic had on so-called “mini-brains.” These cerebral organoids are made up of 3D cultures of neural cells. They’re grown from stem cells. Each mimics a brain inside a human fetus.

These neural organoids were first developed last year at Johns Hopkins University. Since they’re lab grown, there aren’t any thorny ethical issues to deal with. After dosing the mini-brains with DMT, scientists identified the neural pathways the chemical traveled which were later found to be associated with neurodegeneration and inflammation.

Many Westerners today are seeking out shamans to produce ayahuasca tea for their own psychological benefit. Science may back this up. But there could still be dangers. Credit: Apollo. Flickr.

Researchers at the D’Or Institute for Research and Education conducted the study. They were led by Stevens Rehen, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Prof. Rehen said, “For the first time we could describe psychedelic-related changes in the molecular functioning of human neural tissue.”

He added, “Our study reinforces the hidden clinical potential of substances that are under legal restrictions, but which deserve attention of medical and scientific communities.” Identifying these pathways has been a priority in the study of psychedelics. A lack of understanding exactly how these substances affect the brain has stunted the field, thus far.

Each mini-brain was given a single dose of the psychedelic 5-MeO-DMT. This compound comes from the dimethyltryptamine family. One might ingest it after licking a certain kind of toad, Incilius alvarius.

Colorado River toad toad (Incilius alvarius). Credit: H. Krisp [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Researchers used a technique known as mass spectrometry-based proteomics to analyze the mini-brains, once dosed. Nearly a thousand proteins were altered by the chemical, they found. Some were upregulated while others were downregulated. Then the scientists took these proteins and traced them back to what role they play inside the brain.

Prof. Rehen and colleagues found that this psychedelic may ward off brain lesions and inflammation, and inhibit neurodegeneration. This suggests it would be helpful as an antidepressant. Sidarta Ribeiro was a co-author on the study. He’s the director of the Brain Institute at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Ribeiro said, “Results suggest that classic psychedelics are powerful inducers of neuroplasticity, a tool of psychobiological transformation that we know very little about.”

We still don’t know enough about these substances, however. So no one should take them on their own, as they may have other downsides we just aren’t privy to yet, and affect each person differently. More research is required before we can fully understand how these substances change the brain.

Given the high rate of depression these days, new treatment options are sorely needed. Perhaps someday a psychedelic, a derivative of one, or a synthetic based on one, will help patients overcome certain psychiatric disorders.

To learn more about science’s rejuvenated interest of psychedelics, click here: