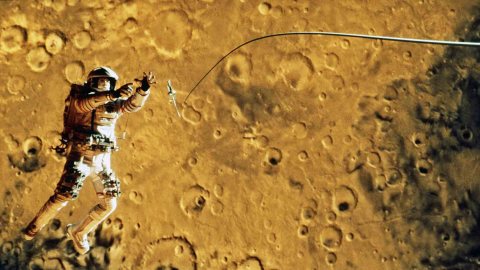

Do We Have the Right to Visit Inhabited Planets? Carl Sagan Said, “No”

Mars has captivated humanity since the time of ancient Babylonian astronomers. In the modern era, the idea of life on Mars has been a focus of such great minds as H.G. Wells, Carl Sagan, and David Bowie. As Big Think has mentionedin the last week or two, plans are underway to take humanity to Mars within the next two decades. President Obama has even channeled John F. Kennedy in his recent endorsement of sending a person to Mars and “returning them safely to the Earth”.

There is no shortage of people who want us to get to Mars, but less noticed among them are the people who ask, “Should we go?”. While the reasons that would compel us to go to Mars are many and substantial there is a vital question that must be considered.

What if there is already life on Mars? Should we still go if there is?

Suppose for a moment that we discovered tomorrow that there was life on Mars, most certainly it would be limited to microscopic life, but it would still be life. It would be the most significant discovery in the history of science. Would mankind be entitled to colonize Mars in this case? Could we claim it was still moral to do so?

One of the greatest advocates of space exploration in the 20th century, Carl Sagan, said no. In the chapter ‘Blues for a Red Planet’ in his book Cosmos, he discusses the idea fully: “If there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes.” When he wrote that in 1980, inconclusive evidence on such life being on Mars from the Viking landers made his statement incredibly relevant.

While we might consider the idea of life on Mars less likely than he did, the question he tries to answer remains important. Especially when mankind moves beyond Mars and towards other candidates for life harboring worlds such as Europa, Titan, or Enceladus.

Sagan was opposed to anthropocentrism, the belief that humans are exceptional or otherwise extremely significant, both on Earth and in the universe. In defending the rights of Martian microbes to their planet, Sagan suggests that all life has great value and that our ability to get to Mars does not constitute a right to colonize it. His position was reflected here on Earth through his support of the Cornell Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, as their faculty advisor.

On the other hand, the argument could be made that the life we are most likely to find on Mars, if any, would be microbial and thus perhaps not entitled to any special rights. After all, who cares for the rights of microbes on Earth?

Consider a few methods of deciding who has certain rights in modern philosophy. They tend to run into the issue of anthropocentrism, and find it difficult to protect the rights, if any, of non-human life. Microbes get left out entirely.

James Griffin’s idea of human rights is based on the notion of Normative Agency, our ability to design and act on a plan of life, and could only be fully applied to humanity at this time. Even if you were to scale rights down with the ability of an animal to use said agency, microbes would be left with nothing.

Kant’s notion of Autonomy is also difficult to apply to anything less intelligent than a human. While it would be possible to support a maxim that respects all life rather than just humanity using his ethics, Kant still relies on the ability of a moral agent to reason, which we generally don’t consider microbes to be able to do. John Rawls, in his Kantian masterpiece A Theory of Justice, excludes animals from having “rights” because of this. In all of his works, he never suggests we owe non-human life anything more than a guarantee to avoid cruelty. His concern for microbes could be considered minimal.

John Stuart Mill’s Utilitarianism perhaps demands that we do invade Mars, as he places the happiness of a human at a much higher value than that of a lower life form. Stating in his classic text Utilitarianism:“it is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question.” The promotion of the total happiness then, calls for us to ignore the risks to microbial life on Mars.

Of course, the opponents of anthropocentrism could point out, perhaps accurately, that humans have a tendency to place high value on traits that they have a monopoly on. When happiness is discussed, we even claim access to a higher form of it. Perhaps we are biased towards our own virtues and value. After all, wouldn’t intelligent eagles value the power of flight and keen vision over having thumbs?

So, should we go to Mars? Or is Mars for the Martians, if any? The question of if there ever was life on Mars to begin with must be resolved first. When it is resolved, we are still faced with the issue of life on other worlds we desire to travel to. Should we invoke the Prime Directive of the Federation when exploring the heavens, or brush aside the bacterium of the cosmos? The philosophical jury is still out.

—