Crashed Israeli lunar lander could have spilled ‘water bears’ on moon

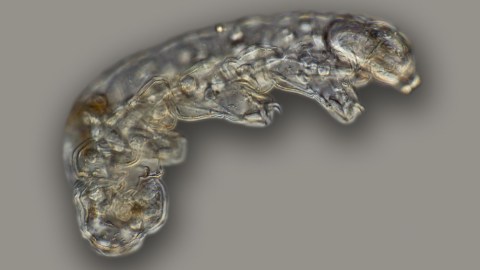

- An Israeli spacecraft carrying tiny animals called tardigrades crashed onto the moon in April.

- It’s unclear whether humans would be able to revive the tardigrades, which were in a dehydrated state.

- Tardigrades have a unique protein that enables them to survive intense levels of radiation.

There are no humans currently on the moon. But it’s very possible that other Earthly animals exist right now on the lunar surface, following the crash of an Israeli lander in April.

The washing-machine-sized spacecraft – Aerospace Industries’ Beresheet – was on a mission to deposit what was basically a digital time capsule on the moon. It contained a primer on humanity and its achievements: thousands of books, DNA samples, textbooks and the secrets to David Copperfield’s magic tricks. It also contained thousands of dehydrated tardigrades – microscopic animals, commonly called “water bears,” known for being able to survive extreme conditions that prove fatal for nearly all other known lifeforms.

But on April 11, 2019, Beresheet’s gyroscopes failed and it crashed into the moon.

“For the first 24 hours we were just in shock,” Nova Spivack, found of Arch Mission Foundation, which seeks to create “a backup of planet Earth,” told Wired. “We sort of expected that it would be successful. We knew there were risks but we didn’t think the risks were that significant.”

The team knew the lander was toast. But subsequent analyses revealed that the lunar library likely survived the crash, meaning the tardigrades might have too. Tardigrades possess the rare ability to essentially stop their metabolism and enter a dormant, desiccated state. Although these tiny creatures only live for a few months, some have been put into a dormant state for 10 years and then were successfully revived. One was even revived after 30 years.

Tardigrades have also survived in this state in space – the first animal to do so. In 2007, Russian astronauts exposed groups of tardigrades to the vacuum and intense radiation of low-Earth orbit for 10 days. Back on Earth, scientists successfully revived 68 percent of the tardigrades. In 2011, an Italian crew conducted a similar experiment, finding that cosmic radiation “did not significantly affect survival of tardigrades in flight, confirming that tardigrades represent a useful animal for space research.”

How are they able to withstand such intense levels of radiation? In a 2016 study published in Nature Communications, researchers found that tardigrades express a unique protein – called “Dsup” – that effectively shields DNA from radiation. Surprisingly, it may be possible to someday give astronauts this rare ability.

“Once Dsup can be incorporated into humans, it may improve radio-tolerance,” geneticist Takekazu Kunieda, co-author of the 2016 study, told Gizmodo. “But at the moment, we’d need genetic manipulations to do this, and I don’t think this will happen in the near future.”

It’s unclear whether the tardigrades on the moon survived the crash, and, if so, whether humans will be able to revive them. But given the extreme places where tardigrades have survived and been discovered, it’s definitely possible.