At the center of almost every galaxy is a gigantic black hole — a place where gravity is so strong, not even light can escape its pull.

Because black holes don’t emit any light, we can’t see them, but we can detect their presence by measuring radio signals emitted by the matter they eject.

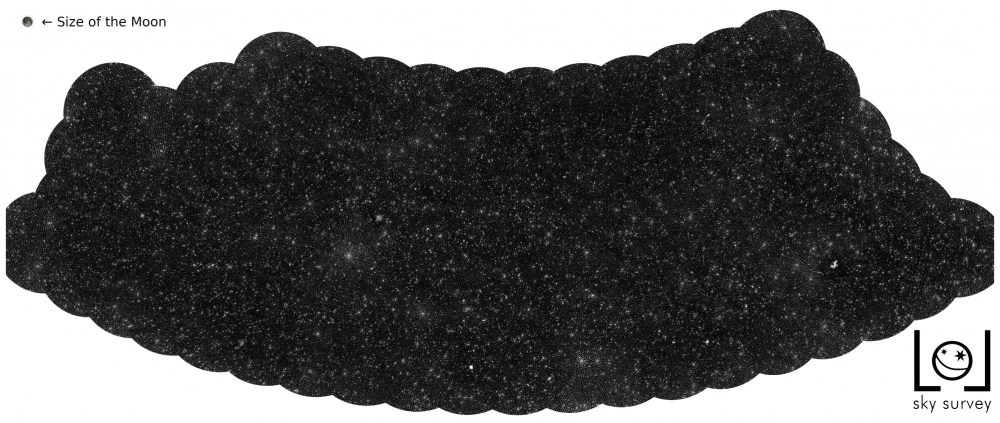

Now, an international team of astronomers has used those signals — with the help of supercomputers and an international telescope array — to create a map of 25,000 of these supermassive black holes.

Supermassive black holes

Supermassive black holes are the largest type we know about — the biggest ever discovered has a mass 66 billion times greater than that of our sun. (In other words, roughly the difference between a Ford pickup truck … and Mount Everest.)

To map where these supermassive black holes are, the astronomers relied on data from the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) radio telescope — a network of about 20,000 antennas spread out across Western Europe.

For 256 hours, the LOFAR network observed the northern sky (all the sky that’s visible from the North Pole) and recorded the radio signals that reached Earth’s surface.

However, those signals were distorted by a layer of Earth’s atmosphere called the ionosphere, which is able to reflect radio signals.

“It’s similar to when you try to see the world while immersed in a swimming pool,” researcher Reinout van Weeren said in a press release. “When you look up, the waves on the water of the pool deflect the light rays and distort the view.”

Supercomputers to the rescue

The astronomers developed algorithms to correct for this distortion, then ran the data through them on supercomputers — the algorithms made adjustments every four seconds during the 256 hours of observations.

Only then were astronomers able to identify and map the supermassive black holes.

“This is the result of many years of work on incredibly difficult data,” lead researcher Francesco de Gasperin said in the press release. “We had to invent new methods to convert the radio signals into images of the sky.”

While 25,000 supermassive black holes might seem like a lot, the newly released map only covers 4% of the northern sky.

The astronomers’ goal is to create one covering the whole northern sky, which should be easier now that they’ve developed the algorithms needed to correct the measurements.

“After many years of software development, it is so wonderful to see that this has now really worked out,” researcher Huub Röttgering said.

This article was reprinted with permission of Freethink, where it was originally published.