The biggest climate change decision: Should you have children?

Climate change has some parents thinking twice about having kids, both to lessen their long-term impact on the environment, and to protect their would-be children from a collapsing world.

In a series of interviews, The New York Times surveyed more than a dozen adults ages 18 to 43 about the role climate change plays in their childbearing decisions. Their answers suggest the environment could be the deciding factor for many would-be parents.

“I don’t want to give birth to a kid wondering if it’s going to live in some kind of ‘Mad Max’ dystopia,” said 32-year-old Allison Guy, who works at a marine conservation nonprofit in Washington.

Other parents echoed similar sentiments.

“Animals are disappearing,” said Amanda PerryMiller, a 29-year-old Christian youth leader from Ohio and mother of two. “The oceans are full of plastic. The human population is so numerous, the planet may not be able to support it indefinitely. This doesn’t paint a very pretty picture for people bringing home a brand-new baby from the hospital.”

Visualization of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Image: NASA

PerryMiller told the Times that after having her first child, climate change made it clear she had to have another.

“Someday, my husband and I will be gone,” she said. “If my daughter has to face the end of the world as we know it, I want her to have her brother there.”

The birthrate in the U.S. has been falling for a decade, largely due to a crippled economy. But the birthrate hit a record low in 2016, and it’s possible fears about the future of the environment contributed to the drop.

Outside of the U.S., environmental threats might be more salient. Studies that show how the Middle East might be too hot for human habitation by 2100 have caused Maram Kaff, who lives in Cairo, to consider what that could mean for her future children:

“I’ve seen how Syrian refugees, who are running from a devastating war, are being treated. Imagine how my children will be treated if they have to flee their country due to extreme weather, drought, lack of resources, flooding.”

“I know that humans are hard-wired to procreate,” she said, “but my instinct now is to shield my children from the horrors of the future by not bringing them to the world.”

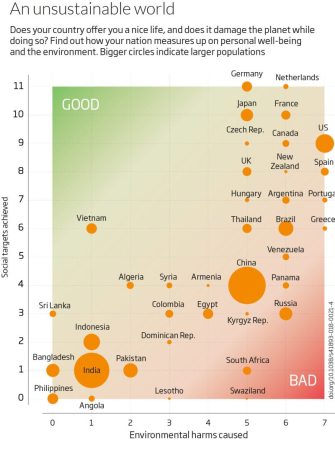

The people surveyed might not be overreacting. A recent analysis that outlines how 151 nations balance sustainability with a comfortable lifestyle shows that, basically, living “well” means wreaking havoc on the planet.

“We didn’t really find a good role model of any country doing things sustainably,” said Daniel O’Neill of the University of Leeds, UK, to New Scientist. “Our analysis is a wake-up call that we need to do things in a radically different way if we are to have any hope of achieving a good life for all people on the planet.”

O’Neill and his team measured how countries used, produced, or affected seven things: water, phosphorus, nitrogen, carbon dioxide emissions, material consumption, ecological footprint, and land-use change.

The gist of the results: Rich nations give citizens comfy lives but far overshoot the limits of sustainability, poor nations do the opposite.

“The analysis provides a critical reminder of the tremendous challenge facing humanity,” said Johan Rockström of Stockholm University in Sweden, to New Scientist. “Suddenly, we must accept that we need to share, in a just and safe way, the remaining biophysical space on Earth, and we’ve never before had to consider this.”

Achieving global stability seems to require far less production and consumption, from developed countries at least.

“We would argue that material de-growth of the richest nations is imperative for medium- and long-term planetary stability,” says Steinberger. “However, in poorer countries, with a lack of basic goods like food and sanitation, some level of growth is essential for social progress.”