Is There Going to Be a Big Hole in History Where the 21st Century Was?

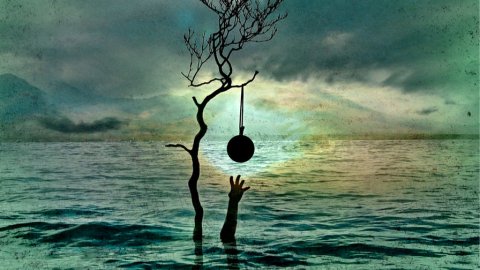

A parent lit in the glow of a monitor types away late into the night, sending notes to the future for his or her children to read upon reaching an age when they want to know who their parents were, what they thought, and what they felt. One day the kids will come across a trunkful of these intimate messages on USB thumb drives, hard drives, or solid-state drives—and have no way to read them. The same will be true for the thousands of digital childhood photos we’ve been taking, and which they’ll be desperate to see. Absent a trip to a hardware archivist or local museum, all this silicon might just as well return to its original form—sand—for all the good it will do. Experts are concerned that this time, now, in the 21st century, may well be the future’s “digital dark age,” with nothing ultimately left behind to tell our story for future generations.

While any hope for true permanence is of course foolish, computer and data experts are concerned we’re digging ourselves a particularly inescapable hole, an “informational black hole,” in the words of Vinton Cerf. As Google data manager Rick West puts it, “We may know less about the early 21st century than we do about the early 20th century.” Cerf tells Science Friday, “Imagine a 22nd-century Doris Kearns Goodwin going back to look at the beginnings of the 21st century.” It’ll just be an incomprehensible stew of baffling gifs and broken web links.

As West notes, this is a new problem: “The early 20th century is still largely based on things like paper and film formats that are still accessible to a large extent, whereas, much of what we’re doing now—the things we’re putting into the cloud, our digital content—is born digital. It’s not something that we translated from an analog container into a digital container, but, in fact, it is born, and now increasingly dies, as digital content, without any kind of analog counterpart.”

(DOVER AIRFORCE MILITARY BASE)

The problem is largely the short lifespan of digital formats, from CDs to floppy drives to Betamax to VHS to DVDs, ad nauseam. Today’s latest and greatest storage medium tends to be utterly useless in just a few years. Journalist and author Cory Doctorow says, “We’re like nautiluses. We go from one device to the next and the next one because storage keeps getting so cheap, has twice as much storage [as] the last ones we had.”

Some say this is really how it’s always been to one extent or another—it just happens to fly square into the face of our fondness for digitally recording every moment of our lives.

The past is always gleaned from bits and pieces, as Kari Kraus of the University of Maryland put it, “We have architectural ruins; we have paintings in tatters. The past always survives in fragments already. I guess I tend to see preservation as not a binary—either it’s preserved or it’s not. There are gradations of preservation. We can often preserve parts of a larger whole.”

Still, remember the room-sized computers in old movies that had big spools of magnetic tape holding their data? Against our sleek, portable devices, tape storage of data seems laughable. But stop laughing. The technology has continued to evolve from the days when a cartridge could hold only 2.3 megabytes of data. The latest tape cartridges from IBM and SONY hold a stunning 330 terabytes each. According to Science Friday’sLauren Young, various big companies—including Google and Fermilab—continue to keep backups, or at least backup of backups, on tape.

Another possible solution is storing massive stockpiles of data on long-lasting synthetic DNA. According to Young, talking to PRI, “Basically, researchers have found a way to store data onto DNA, which is a billion-year-old molecule that can store the essence of life.” And the capacities leave even terabytes in the dust. We’re talking petabytes, millions of gigabytes.

“A single gram of DNA could, in principle, store every bit of datum ever recorded by humans in a container about the size and weight of a couple of pickup trucks,” according to Science Magazine. For now, though, it’s too pricey and slow, costing about $7,000 to get just two megabytes encoded, and another $2,000 to read it back. But, as we’ve seen over and over—indeed, this is part of the problem—most tech gets cheaper with time.

And time is the ultimate problem anyway, so maybe it’s okay in the long run. If our kids could read, watch, and listen to our minute-by-minute digital accounts of our lives after all, when would they have time to live their own?