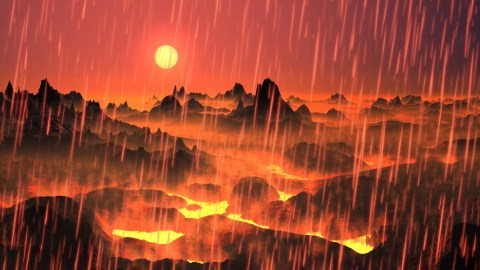

ESO astronomers observe exoplanet where it rains molten iron

Image source: diversepixel/MrVander/Shutterstock/Big Think

- WASP-76b is an extremely hot planet whose cooler side has a surface temperature of 1,500° C (2732° F).

- Iron that evaporates in the heat of the planet’s day side rains down in molten form on the night side.

- ESO learned more about the planet’s intense climate thanks to its new ESPRESSO (Echelle Spectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations) instrument.

Let’s imagine you’re vacationing on WASP-76b, a gas-giant exoplanet in the constellation Pisces, some 640 light-years away. The good news is that you’re on the super-hot planet’s “cool” side. The bad news? Molten iron is raining down and drifting your way from the hot side. “One could say that this planet gets rainy in the evening, except it rains iron,” notes astronomer David Ehrenreich of the University of Geneva in Switzerland.

A hellish place to visit

WASP-76b is one of the most extreme exoplanets astronomers have laid eyes on so far, and both its day and night sides are way to hot for us. It was first identified using the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) Cerro Paranal, 2,600 meters above sea level in the super-dry Atacama Desert in Chile. Recent observations of the gas giant’s chemistry by the ESO VLT’s ESPRESSO instrument revealed its bizarre extremes and iron rain. ESPRESSO is an acronym for the “Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations.”

WASP-76b is “tidally locked” to its star, meaning that the same side is always facing its sun. The day side gets up to 2400° C (4352°F) while the night side maxes out at a balmy 1,500° C (2732° F).

That day side is so hot that molecules separate into atoms, and metals like iron evaporate into the blistering atmosphere. ESPRESSO’s data posed an intriguing question. “The observations show,” says astrophysicist María Rosa Zapatero Osorio, “that iron vapor is abundant in the atmosphere of the hot day side of WASP-76b.” However, that strong iron signature at the evening boundary between the two sides of WASP-76b was nowhere to be seen near the morning edge. Where could it go? Astronomers believe that the atmospheric and rotational winds carry a fair amount of the iron vapor to the night side where it falls as molten iron rain.

Image source: Jurik Peter/Shutterstock

Because exoplanets are always so normal?

Well, not really. While searching for Earth-like exoplanets, astronomers keep finding a planets that definitely don’t qualify.

WASP-76b is way too hot, for example, but it’s hardly the only orbiting inferno. Consider HD 149026b, whose surface temperature is just slightly cooler than WASP-76b, coming in at just over 2,000° C (3632°F).

Then there’s OGLE-2005-BLG-390Lb, a big — 5.5 times the size of Earth — rocky sphere that’s so so cold: -220° C (-364°F). Brrr.

SWEEPS-10 is really close to its star, just 1.2 million kilometers, and races around its sun every 10 hours, as opposed to our roughly 365 days. That proximity means that it’s particularly vulnerable to eventually being pulled apart, unless it slips away. And CoKu Tau/4 is just a mere babe, only a million years old.

Image source: ESO/M. Zamani/Wikimedia

An immediate win for ESPRESSO

Credit for the new, deeper understanding of WASP-76b must go to ESPRESSO, which was designed to help search for Earth-like planets around Sun-like stars. In fact, the WASP-76b insights were derived from the instrument’s very first observations made in September 2018 by the scientific consortium of experts from Portugal, Italy, Switzerland, Spain and the ESO responsible for the instrument.

Insights such as these have changed the way scientists see ESPRESSO. It’s not just for finding exoplanets, but also helping explain them. “We soon realized that the remarkable collecting power of the VLT and the extreme stability of ESPRESSO made it a prime machine to study exoplanet atmospheres,” says Pedro Figueira, ESPRESSO instrument scientist at ESO in Chile.

Meanwhile the search for additional exoplanets continues. At the time of writing, 4,135 exoplanets have been found with 55 of them considered potentially habitable by life as we know it.