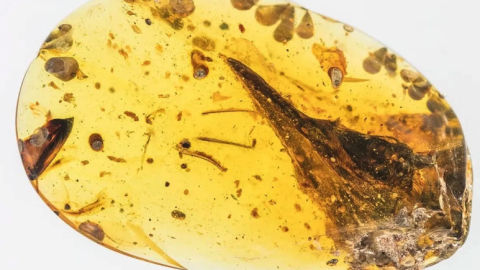

Smallest known dinosaur found in 99-million-year-old amber

Xing Lida / CC BY-ND

- The amber-trapped specimen was found in Myanmar in 2016.

- The specimen was a bird-like dinosaur that likely preyed on insects and small invertebrates.

- The researchers said their findings, if correct, show that miniaturization of dinosaurs occurred much earlier than paleontologists previously thought.

When you imagine dinosaurs of the Mesozoic era, 248 to 65 million years ago, you might imagine unfathomably huge and monstrous creatures. After all, this era, which included the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, brought to the world massive creatures that spanned more than 50 feet long, like the Brachiosaurus and the Spinosaurus. But not every Mesozoic dinosaur deserved names like Giganotosaurus.

Case in point: Oculudentavis khaungraae, a tiny bird-like creature recently discovered in 99-million-year-old amber. With a skull less than 2 centimeters long, the dinosaur would’ve been comparable to the thumb-sized bee hummingbird, the smallest living bird. That makes it one of the tiniest dinosaurs ever discovered.

“When I first saw this specimen, it really blew my mind,” Jingmai O’Connor, senior professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and a research associate at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, told CNN. “I literally have never seen anything like this.”

The researchers published their findings in the journal Nature.

Artist’s impression of Oculudentavis preying on an insect. (Han Zhixin)

The dinosaur’s size wasn’t its only peculiar trait. Oculudentavis khaungraae, which means eye-tooth bird, had bulging, lizard-like eyes that faced to the side, as well as a beak that wielded at least 23 sharp teeth, suggesting it preyed on tiny insects and invertebrates. It likely weighed about 2 grams.

Paleontologists don’t usually find tiny, delicate dinosaurs like this in the fossil record. However, millions of years ago, tiny creatures like Oculudentavis did get occasionally trapped in gobs of amber, which are especially good at preserving animal specimens over millennia.

The piece of amber that encased this specimen was found in 2016 in a mine in Myanmar. After it was donated to the Hupoge Amber Museum in China, a team of paleontologists began studying it to learn more about the dinosaur, and where exactly it fits on the evolutionary tree. Birds, after all, descended from dinosaurs, though it’s unclear how and when this evolutionary transition occurred.

A CT scan of the skull. (Li Gang)

One especially curious aspect of this transition was how ancient birds, or bird-like dinosaurs, got to be so tiny. But the researchers had an explanation: isolation.

“This process — called miniaturization — commonly occurs in isolated environments, most famously islands,” O’Connor told CNN. “It is no wonder that the 99-million-year old Burmese amber is thought to have come from an ancient island.”

If the researchers are correct, the discovery of Oculudentavis means that the miniaturization of dinosaurs “peaked far earlier than paleontologists previously thought,” as and O’Connor and study co-author Lars Schmitz wrote in a piece for The Conversation. Still, the discovery also raises many questions that scientists have yet to answer.

“Our work demonstrates how little scientists know about the little things in the history of life,” they wrote in the blog post. “Scientists’ snapshot of fossil ecosystems in the dinosaur age is incomplete and leaves so many questions unanswered. But paleontologists are eager to take on these questions. What other tiny species were out there? What was their ecological function? Was Oculudentavis the only visually guided bug hunter? To better understand the evolution of the diversity of life we need more emphasis and recognition of the small.”

Artist’s impression of Oculudentavis alive 99 million years ago. (Han Zhixin)

Studying dinosaurs trapped in amber is an especially valuable way for scientists to learn more about our evolutionary past. In a video published by Nature, O’Connor seemed optimistic about how technology might soon allow paleontologists to learn even more about these unusual amber time capsules.

“I’m hoping in the next 10 years that we’re going to develop techniques that are going to allow us to access the biochemistry of the soft tissues that are preserved in there,” she said. “I’m actually sitting on quite a few amazing specimens that I haven’t had time to study yet, but there’s a lot of very cool things that we still have, like on the back burner, that we’ll be studying very soon. So stayed tuned. There’s a lot more cool stuff out there.”