3 new studies indicate a conflict at the heart of cosmology

- Telescopes are essentially time machines. As we examine galaxies that are at greater and greater distances from the Earth, we are looking further and further back in time.

- A new series of studies that examine the “clumpiness” of the Universe indicates that there might be a conflict at the heart of cosmology.

- The Big Bang theory is still sound, but it may need to be tweaked.

A series of three scientific papers describing the expansion history of the Universe is telling a confusing tale, with predictions and measurements slightly disagreeing. (The papers can be accessed here: one, two, three.) While this disagreement isn’t considered a fatal disproof of modern cosmology, it could be a hint that our theories need to be revised.

Creation stories, both ancient and modern

Understanding exactly how the world around us came into existence is a question that has bothered humanity for millennia. All around the world, people have devised stories — from the ancient Greek legend of the creation of the Earth and other primordial entities from Chaos (as first written down by Hesiod) to the Hopi creation myth (which describes a series of different kinds of creatures being created, eventually ending up as humans).

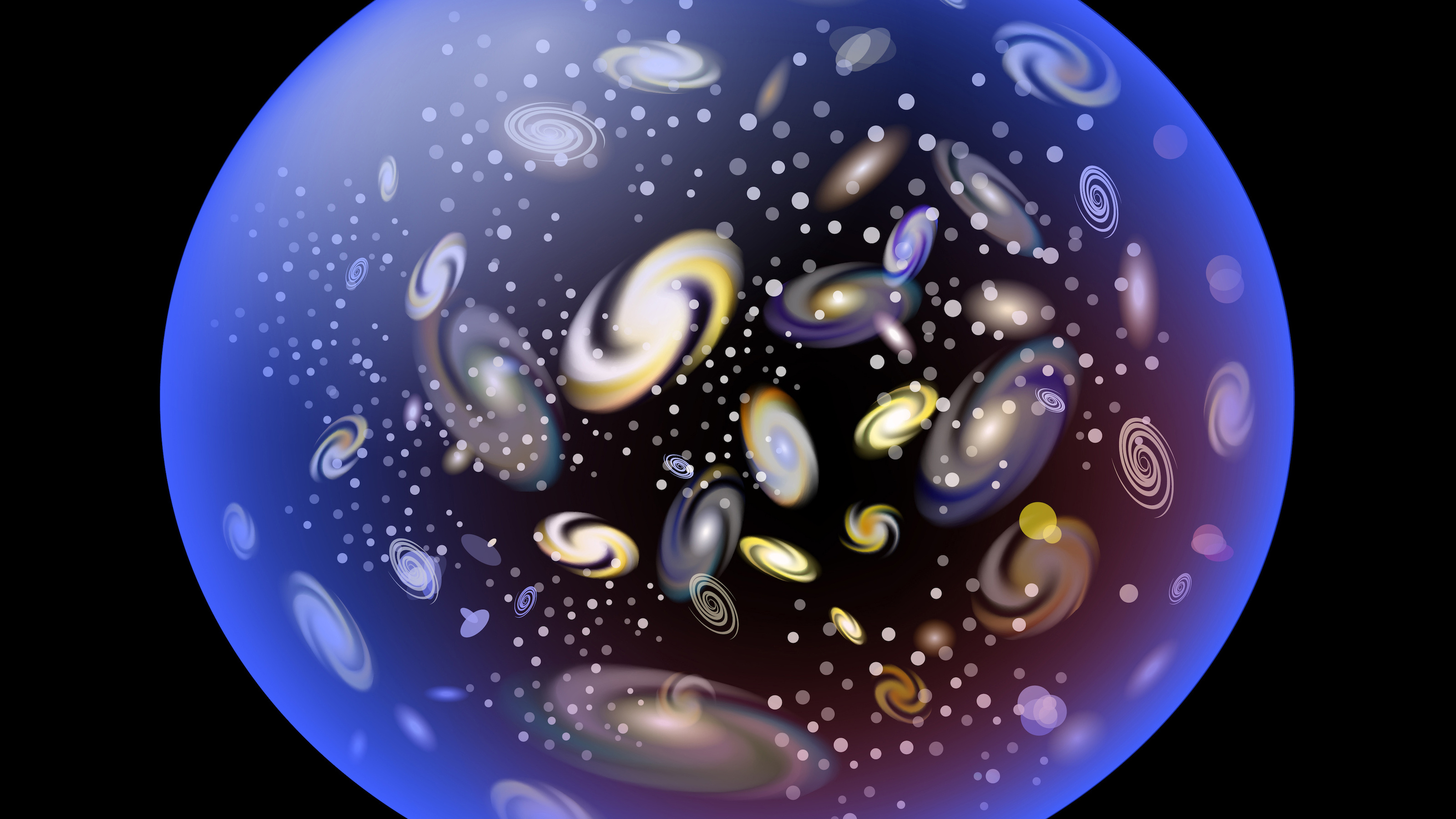

In modern times, there are still competing creation stories, but there is one that is grounded in empiricism and the scientific method: the idea that about 13.8 billion years ago, the Universe began in a much smaller and hotter compressed state, and it has been expanding ever since then. This idea is colloquially called the “Big Bang,” although different writers use the term to mean slightly different things. Some use it to refer to the exact moment at which the Universe came into existence and began to expand, while others use it to refer to all moments after the beginning. For those writers, the Big Bang is still ongoing, as the expansion of the Universe continues.

The beauty of this scientific explanation is that it can be tested. Astronomers rely on the fact that light has a finite speed, which means that it takes time for light to cross the cosmos. For example, the light we see as the Sun shining was emitted eight minutes before we see it. Light from the nearest star took about four years to get to Earth, and light from elsewhere in the cosmos can take billions of years to arrive.

The telescope as a time machine

Effectively, this means that telescopes are time machines. By looking at more and more distant galaxies, astronomers are able to see what the Universe looked like in the distant past. By stitching together observations of galaxies at different distances from the Earth, astronomers can unravel the evolution of the cosmos.

The recent measurements use two different telescopes to study the structure of the Universe at different cosmic epochs. One facility, called the South Pole Telescope (SPT), looks at the earliest possible light, emitted a mere 380,000 years after the Universe began. At that time, the Universe was 0.003% its current age. If we consider the current cosmos to be equivalent to a 50-year-old person, the SPT looks at the Universe when it was a mere 12 hours old.

The second facility is called the Dark Energy Survey (DES). This is a very powerful telescope located on a mountain top in Chile. Over the years, it has surveyed about 1/8 of the sky and photographed over 300 million galaxies, many of which are so dim, they are about one-millionth as bright as the dimmest stars visible to the human eye. This telescope can image galaxies from the current day to as far back as eight billion years ago. Continuing with the analogy of a 50-year-old individual, DES can take pictures of the Universe starting when it was 21 years old up until the present. (Full disclosure: Researchers at Fermilab, where I also work, carried out this study — but I did not participate in this research.)

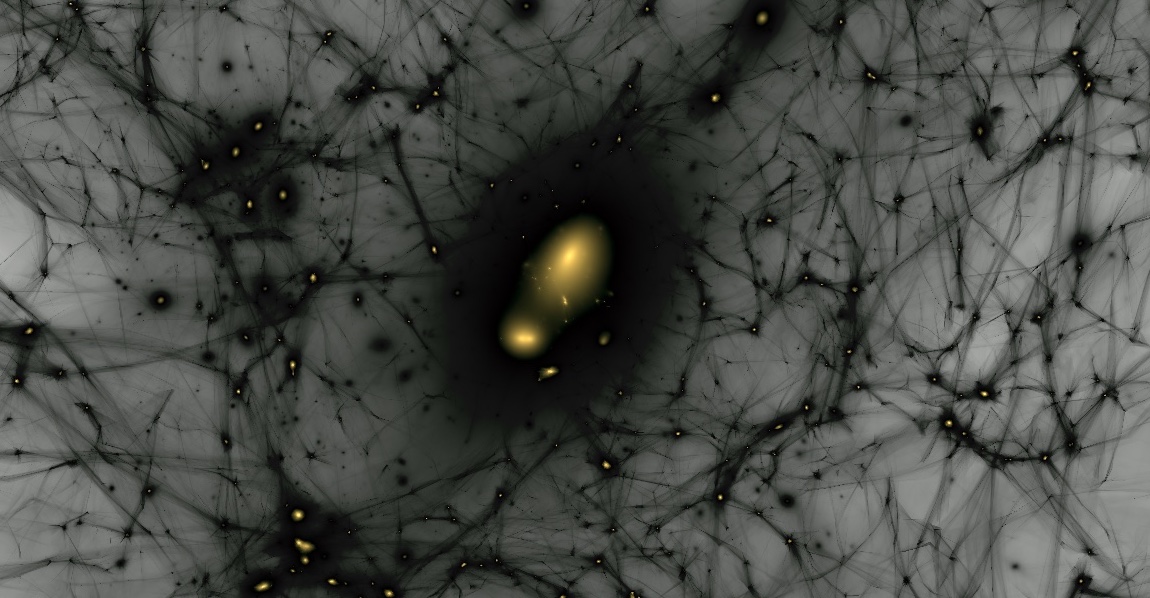

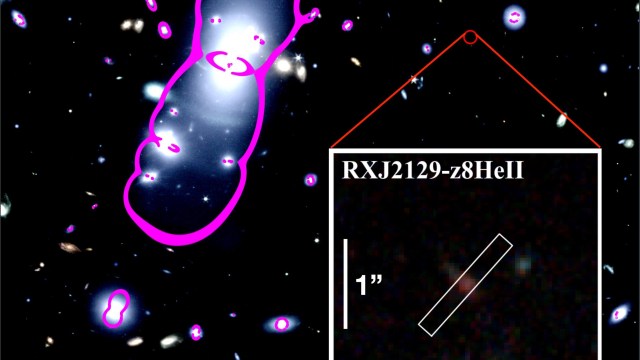

As light from distant galaxies travels to Earth, it can be distorted by galaxies that are closer to us. By using these tiny distortions, astronomers have developed a very precise map of the distribution of matter in the cosmos. This map includes both ordinary matter, of which stars and galaxies are the most familiar examples, and dark matter, which is a hypothesized form of matter that neither absorbs nor emits light. Dark matter is only observed through its gravitational effect on other objects and is thought to be five times more prevalent than ordinary matter.

Is the Big Bang incomplete?

In order to test the Big Bang, astronomers can use measurements taken by the South Pole Telescope and use the theory to project forward to the present day. They can then take measurements from the Dark Energy Survey and compare them. If the measurements are accurate and the theory describes the cosmos, they should agree.

And, by and large, they do — but not completely. When astronomers look at how “clumpy” the matter of the current Universe should be, purely from SPT measurements and extrapolations of theory, they find that the predictions are “clumpier” than current measurements by DES.

This disagreement is potentially significant and could signal that the theory of the Big Bang is incomplete. Furthermore, this isn’t the first discrepancy that astronomers have encountered when they project measurements of the same primordial light imaged by the SPT to the modern day. Different research groups, using different telescopes, have found that the current Universe is expanding faster than expected from observations of the ancient light seen by the SPT, combined with Big Bang theory. This other discrepancy is called the Hubble Tension, named after American astronomer Edwin Hubble, who first realized that the Universe was expanding.

While the new discrepancy in predictions and measurements of the clumpiness of the Universe are preliminary, it could be that both this measurement and the Hubble Tension imply that the Big Bang theory might need some tweaking. Mind you, the discrepancies do not rise to the level of scrapping the theory entirely; however, it is the nature of the scientific method to adjust theories to account for new observations.