Why A Good Life Need Not Be a Long Life

“I know I will not make old bones,” says Achilles in Christopher Logue’s modern Iliad. I personally have seen enough old people staring, drooling, groaning and pissing into their giant diapers to sympathize with a wish to quit while you’re still ahead. Today, though, we’re all supposed to want to live forever. It’s not enough to be sad about Amy Winehouse’s death at 27 this week. We’re expected to feel something like outrage, because no one is supposed to die that young.

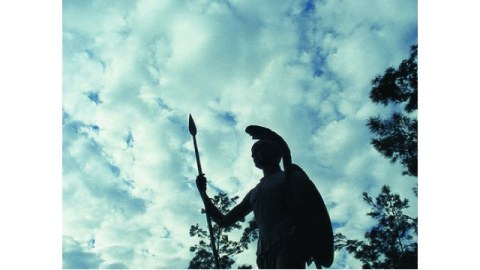

Other eras had a different view. In Book Nine of the Iliad Achilles recounts how his immortal mother had given him a choice. He could have a long, tranquil life at the end of which he would, like most of us, be utterly forgotten—or a life of triumph and glory, which would leave his name shining brightly for thousands of years. But that life would be short. As you’re reading about him 3,000 years later, you know what he decided.

Which is hard to get the modern head around. With our technologies for life extension we think it normal to live past 65, 75, or even 85. This is one reason many nations are on the long-term road to insolvency: when the U.S. Social Security program was instituted in 1935, only half of men who lived to 21 could expect to make it to the retirement age of 65. Now nearly everyone makes it, which is threatening to bankrupt future generations.

Why do we think longevity so natural and right? In part, I think, it’s because we think of it as the byproduct of living well: We like to think the traits that make life sweet are those that make it long. But this long-term study of longevity over decades suggests that’s not so. Over 20 years, Howard S. Friedman, a psychologist at the University of California, Riverside, and his colleagues studied 1,500 “gifted” children identified in 1921 by Louis Terman, a psychologist at Stanford. Friedman’s team looked at the lifetime data on these kids, who were about ten when first identified—their relationships, their personalities (as reported by teachers and parents) educations, work history and so on.

Of course, some of the kids in the study were more cheerful and optimistic than others. Some had better sense of humor. On average, they died sooner. Similarly, people who seemed happy-go-lucky and didn’t stress about work also died at younger ages. And people who reported they felt loved and cared for? Also less likely to life longer. Friedman et al. believe the sunnier people were too cheerful for the long haul—expecting things to work out, they took too many risks.

Who did that leave to win the longevity sweepstakes? As the Publisher’s Weekly review put it, “If there’s a secret to old age, the authors find, it’s living conscientiously and bringing forethought, planning, and perseverance to one’s professional and personal life.”

In other words, if you want to live long, you’re better off being a bit of a buzzkill, with a touch of the bore. Plod along, don’t stand out, eat your peas, get your mammogram and count your pennies. Society needs such people, for sure. But in a choice between an MP3 of Amy Winehouse singing and one of these citizens discussing their tax strategy, I’ll take the late Ms. Winehouse, thank you. Society benefits from people with the charm, joy in the moment, monomaniacal dedication and lack of interest in self-preservation that seem to make for a shorter life. We don’t all need to make old bones.

Winehouse died at 27, which is strikingly young (it’s close to half my age, and I’d have hated to miss the past 26 years) but, as a number of media outlets reported, other stars have blown out at exactly the same age (Kurt Cobain, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison). Many others went at roughly the same time in life (Heath Ledger, James Dean). The briefness of their time on Earth is sad; but mourning an individual does not require us to believe that no life should be brief.

That’s the theme of this wonderful essay by Dudley Clendinen, a longtime Timesman who has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and who is clear, at age 66, that he is not interested in becoming “a conscious but motionless, mute, withered, incontinent mummy of my former self.” Lingering on, he writes, “would be a colossal waste of love and money.” Instead, he says, simply: “I’d rather die.”

Until that moment comes, Clendinen says, he is having a good time, appreciating what he calls “the Good Short Life.” He believe it is fine, sweet and decorous—fully and naturally human—not to make old bones. We could use more of this strain in our national conversation. In which we assume (if talking about future Federal deficits) that millions of people can and should live as close to forever as they can. In which we assume (if talking about our own lives) that we’re obligated to hang on until the last machine-aided breath. In which we assume, if talking about technology, that the right question is how it can extend our lease on Earth for centuries—instead of asking what point and value all those lingering years might have.

It is sad to exit at age 27, or even at age 66. But it doesn’t mean one didn’t have a good life.