Editor’s Note: Lea Carpenter writes the English Lessons column for Big Think about what we can learn from the writing we love. She interviewed former Navy SEAL Eric Greitens for Big Think, and wrote this post.

Everyone knows “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” That line, spoken first fifty years ago, has unique resonance for what journalists are now calling “The Nine Eleven Generation.” They rose to President Kennedy’s challenge. They did not let America’s greatest national tragedy break them. What will Monday mean for them? How will its legacy define their lives over time?

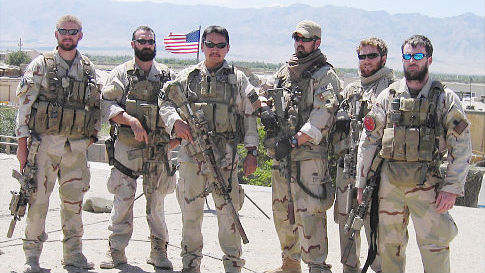

As Lea Carpenter writes, Eric Greitens joined the Navy SEALs “in another era, when the choice to serve may have seemed slightly less stressful.” Watch the video here:

What’s the Big Idea?

One set of voices we won’t hear from as much as we might like to this week are those of the men and women in the U.S. Military. On par, they’re working too hard to take time to appear on Morning Joe. Most work hard knowing they will receive little reward and less recognition, and while many of those now serving have served since before Al-Qaeda was a well-known name, others chose the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines directly in the wake of September 11th. Some made that choice because they wanted to help their country in a time of crisis; some simply felt it was a more meaningful option that all the others.

It’s a lie that the military is the only choice for those who choose it; service in war-time still offers something neither the Ivy League nor Wall Street can match: a chance to participate in a mission. Eric Greitens joined the Navy in another era, when the choice to serve may have seemed slightly less stressful. But his concept of service, informed by his choice and his experience, is applicable across industries, temperaments, and demographic lines. It’s even relevant for those of us will never have the chance to join the Special Forces. Greitens puts it like this:

“Now, the Navy said to me, ‘If you join, we’re going to pay you $1,332.60 per month. If you join, we guarantee that you will have zero minutes per day of privacy in your first few months.’ Now, in some way, it wasn’t such a compelling offer . . . I realized that a university career at Oxford could give me a lot of freedom. Consulting could give me a lot of money. The Navy was going to give me very little, but would make me more. I think that whenever you or whenever we are facing these decisions in our lives, if we ask ourselves the question, ‘Which decision, which path on our journey is going to make us more’—I think we’ll always be happy with the choices that we make.”

What’s the Significance?

Most people want to be “made more.” The men and women who made the choice to serve ten years ago have grown up alongside and within the “war on terror.” Their reflections will one day prove as powerful as those collected from other wars.

This generation—of soldiers and sailors, doctors and operators, JAGs and intelligence analysts, anyone who serves—has no name. It’s too soon. Tom Brokaw called World War II veterans “the Greatest Generation” only fifty years following the last cease-fire. “The Nine Eleven Generation” doesn’t feel right—or fair. The shock of loss lengthens and shifts, into the challenge of respectful reflection. Americans are excellent at honoring loss; we will do our best to respect the memory of those lost on that day. An equally crucial challenge is how best to respect, and understand, those who’ve given their lives to the fight in the intervening years.

English author Martin Amis concluded his 2008 collection The Second Plane with an essay titled “September 11.” Its last lines were:

“September 11 entrained a moral crash, planet-wide; it also loosened the ground between reality and delirium. So when we speak of it, let’s call it by its proper name; let’s not suggest that our experience of that event, that development, has been frictionlessly absorbed and filed away. It has not. September 11 continues, it goes on, with all its mystery, its instability, and its terrible dynamism.”

Of course “it goes on:” we are all the Nine Eleven generation now.