The Joy of Antique Wikipedia Entries

Wikipedia is universally relied on and universally distrusted. On the one hand, it’s a stunning repository of knowledge that has rendered the World Books of my not-so-distant childhood utterly obsolete; on the other hand, it’s always partly tethered to the wisdom of crowds, meaning that diligent scholars and fact-checkers must perform a two-step: look it up on Wikipedia, then confirm it elsewhere.

Studies have shown that Wikipedia’s accuracy rate compares well with that of “official” encylopedias, which can’t be updated as fast or expanded as comprehensively. And yet there are still those occasional articles that land it shy of perfect respectability…

My favorite irregularities aren’t the glaring errors, the garbled sentences, or the instances of cheerful bias (from an article on Indian mystic Swami Shivananda: “Though his suffering was intense, he was always happy, as he never felt alienated from his Lord whose presence he was constantly aware of”). No, what I love most are the passages ingested from old public-domain reference books. So many articles borrow from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, for example, that the site has developed a special attribution template for editors to use in annotating them.

And yet what must give Jimmy Wales fits gives my heart convulsions of delight. It’s sheer magic: flyblown tomes you’d otherwise never encounter are suddenly thrust under your nose. People and events with zero impact on the modern world somehow become relevant again. Need to learn about New Hampshire conchologist Augustus Addison Gould? Of course you don’t, but thanks to the zombified 1911 Britannica, you can!

It’s easy enough to seek these anachronisms out, but it’s even more fun when you find them by accident. If libraries die, this may become the closest future generations get to the special kind of serendipity they provide. Recently I stumbled across an entry on painter Joshua Cristall, which contained the following excerpt from Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravings (1886–89):

He was first apprenticed to a china dealer at Rotherhithe, but, finding that business too irksome, he left both his master and his home, and went to the Potteries, where he found some employment as a china painter. Finding this too monotonous, he came to London, and commenced a life of great privations and hard efforts to study the fine arts. It is said that at this period of his life he seriously injured his health by trying to live for a year on nothing else but potatoes and water.

Try getting that kind of information from the World Book.

By the time you click the links above, by the way, the articles may very well have been brought up to date. The Wikignomes are sleepless. Their system, mostly, works.

But I hope it never works too well. Encyclopedias by their nature are quixotic endeavors—what resource can seriously hope to provide all the knowledge in the world?—so it’s fitting that they should contain a little romance. Maybe even some sobering wisdom, as in the entry on Crinoline:

The crinoline had grown to its maximum dimensions by 1860. However, as the fashionable silhouette never remains the same for long, the huge skirts began to fall from favour.

Ah, how true: style is fleeting. But old-timey anecdotes are hilarious forever:

However there is one instance of a crinoline possibly saving a life, in the case of Sarah Ann Henley who jumped off the Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol in 1885 after a lover’s quarrel, but survived the 250 ft drop because her skirts supposedly acted like a parachute and slowed her descent. Although it is debated if the skirt actually saved Ms. Henley from the fall, the story has nevertheless become a local Bristol legend.

That entry, by the way, doesn’t properly cite its sources, so I have no idea where this yarn comes from. Once in a while, it’s better not to know.

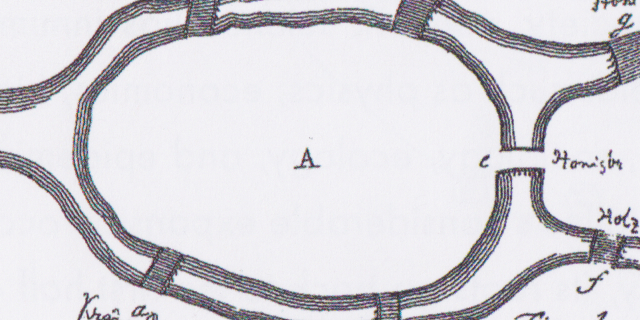

[Image from Crinoline article, Wikipedia. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.]