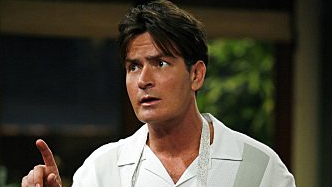

The Desperate Man: Charlie Sheen, Performance Artist?

Like way too many Americans, I, too, have been captivated by the fast-moving human train-wreck slash slow-motion suicide phenomenon of Charlie Sheen. Not since Hot Shots! Part Deuxhave I watched as much footage of Martin Sheen’s youngest and most likely craziest son. Fueled by “Adonis DNA” and inspired by his “Goddess” muses, Charlie Sheen’s been playing the part of his and maybe our lifetime to what may be the last drop of his “Tiger blood.” Performance art usually receives condescending smirks in the United States as the last kid picked for the cultural game of kickball. With Charlie Sheen’s big adventure, however, maybe performance art has finally come to the colonies.

Joseph Beuys kick started performance art post-World War II. In How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Beuys coated his head in honey and gold leaf while living up to the promise of the title and explaining pictures to a dead bunny nestled in his arms. Surrounded by all the bizarre things that took place in the 1960s, Beuys mid-decade performance piece actually seemed fairly tame at the time and seems almost quaint today. If and assuredly when Sheen divulges the details of his evenings with his live-in porn actresses, I’m sure honey will be somewhere on a long 9½ Weeks-esque shopping list of party aids.

Less gentle forms of performance art began well before Beuys slathered up. When Vincent Van Gogh sliced off a chunk of earlobe in 1888 as an early Christmas gift for a prostitute named Rachel, he inadvertently inaugurated performance art as a modern art genre, albeit for a posthumous audience as nearly nobody really knew who Van Gogh was in 1888 save for family, friends, and that freaked-out prostitute. In 1963 (two years before Beuys and his bunny), a Vietnamese Buddhist monk named Thích Quảng Đức committed self-immolation in protest of Ngô Đình Diệm’s government—an act captured in a iconic photo years later used as the cover of Rage Against the Machine’s debut album. His act inspired a whole generation of performance artists, including Marina Abramovic, who sliced and diced her body in the name of self-actualization and cultural criticism. Chris Burden took the monk’s example of enduring pain (he remained upright for several minutes as the flames consumed him) and took it to a near-death extreme by allowing himself to be crucified on a Volkswagen in 1974 and, three years earlier, to be shot in the arm by an assistant. Sheen’s brushed shoulders with the reaper several times thanks to his substance abuse, but there’s really nothing artistic about death by drugs.

Where I see the strongest parallels between Sheen’s act and previous artists is in the self-publicizing wing of the performance art museum. Exhibit A: Gustave Courbet. When Courbet painted The Desperate Man in 1843, he was desperate for attention above all else, which is ultimately what Crazy Charlie is all about. “I am the most outrageous man in Paris,” Courbet announced, hoping people would believe it was true. Sheen seems to be saying, shouting, Skyping, and Twittering the same thing—a tribute more to modern technology than to the originality of his goal or methods. Maybe America can finally embrace its first mainstream performance artist in Sheen. (Burden’s brief infamy faded when he retired from trying to kill himself for art.) But what is the price that we pay as we watch Sheen pay the price of respectability, his career, and, most likely, his life? Is Sheen an artist of desperation or have we—addicts to reality television as an escape—elevated our collective desperation to an art?