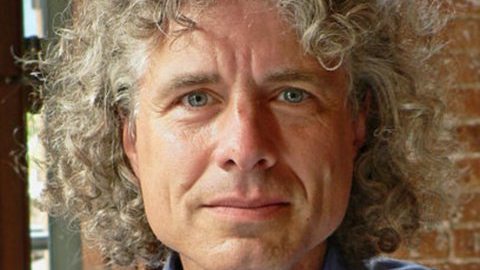

Steven Pinker on Reason and the Decline of Violence

Quibbles about measurement aside, I agree with Steven Pinker that humans have become astoundingly more peaceful over the past several centuries. What I found unsatisfactory about Better Angels of Our Natureis precisely the rationalist element of Pinker’s explanation for the decline of violence which Peter Singer singles out for praise, and nicely summarizes, in his laudatory NYT review:

To readers familiar with the literature in evolutionary psychology and its tendency to denigrate the role reason plays in human behavior, the most striking aspect of Pinker’s account is that the last of his “better angels” is reason. …

Pinker’s claim that reason is an important factor in the trends he has described relies in part on the “Flynn effect” — the remarkable finding by the philosopher James Flynn that ever since I.Q. tests were first administered, the scores achieved by those taking the test have been rising. … One theory is that we have gotten better at I.Q. tests because we live in a more symbol-rich environment. Flynn himself thinks that the spread of the scientific mode of reasoning has played a role.

Pinker argues that enhanced powers of reasoning give us the ability to detach ourselves from our immediate experience and from our personal or parochial perspective, and frame our ideas in more abstract, universal terms. This in turn leads to better moral commitments, including avoiding violence. It is just this kind of reasoning ability that has improved during the 20th century. He therefore suggests that the 20th century has seen a “moral Flynn effect, in which an accelerating escalator of reason carried us away from impulses that lead to violence” and that this lies behind the long peace, the new peace, and the rights revolution.

Singer is right that “the most striking aspect of Pinker’s account” is the heavy explanatory weight he loads onto reason. That evolutionary psychology denigrates the role of reason in human behavior is not incidental. According to the sort of evolutionary psychology to which I take Pinker to subscribe, there is no such thing as capital ‘R’ Enlightenment reason. This is the objection I pressed in my ridiculously short (and I’m sorry to say oversimplified) review of Better Angels for The Daily:

Pinker is among the world’s foremost evolutionary psychologists. The prevailing Darwinian view, to which Pinker subscribes, is that the mind is a cluster of interrelated “modules” selected by evolutionary pressures to perform specialized tasks. But there is no general-purpose reasoning module. Rationality, in its abstract, impartial Enlightenment glory, does not come naturally to us. Pinker understands this. “Humans were not, of course, created in a state of Original Reason,” he says.

But then how does reason develop? Pinker expects that “as collective rationality is honed over the ages, it will progressively whittle away at the short-sighted and hot-blooded impulses toward violence, and force us to treat a greater number of rational agents as we would have them treat us.”But how did rationality get this far? How did it get off the ground in the first place? How does it spread? How does it stick? If the progress of morality depends finally upon the progress of reason, Pinker owes us a fuller account of how mental modules meant for other purposes were made to work in concert to produce something like Enlightenment reason. He owes us an account of how this discipline of mind is cultivated, “honed over the ages,” and passed along culturally. If the key to the astounding decline in human cruelty and death is the cultural evolution of reason, I’d like to hear rather more about it.

Pinker’s account of the development of reason seems to me quite thin. Here’s much of what he has to say about it:

Humans, of course, were not created in a state of Original Reason. We descended from apes, spent hundreds of millennia in small bands, and evolved our cognitive processes in the service of hunting, gathering, and socializing. Only gradually, with the appearance of literacy, cities, and long-distance travel and communication, could our ancestors cultivate the faculty of reason and apply it to a broader range of concerns, a process that is still ongoing. One would expect that as collective rationality is honed over the ages, it will progressively whittle away at the shortsighted and hot-blooded impulses toward violence, and force us to treat a greater number of rational agents as we would have them treat us

Our cognitive faculties need not have evolved to go in this direction. But once you have an open-ended reasoning system, even if it evolved for mundane problems like preparing food and securing alliances, you can’t keep it from entertaining propositions that are consequences of other propositions. When you acquired your mother tongue and came to understand This is the cat that killed the rat, nothing could prevent you from understanding This is the rat that ate the malt. When you learned how to add 37 + 24, nothing could prevent you from deriving the sum of 32 + 47. Cognitive scientists call this feat systematicity and attribute it to the combinatorial power of the neural systems that underlie language and reasoning. So if the members of species have the power to reason with one another, and enough opportunities to exercise that power, sooner or later they will stumble upon the mutual benefits of nonviolence and other forms of reciprocal consideration, and apply them more and more broadly.

Consider the passage I’ve emphasized. All the work here is accomplished by “sooner or later.” Why didn’t humans become as peaceful as we are today tens of thousands of years ago if just falls out the systematicity of our cognitive apparatus given enough opportunity for positive-sum interaction? Well, in the previous paragraph Pinker says, “Only gradually, with the appearance of literacy, cities, and long-distance travel and communication, could our ancestors cultivate the faculty of reason and apply it to a broader range of concerns…” So what’s the story? That given our evolved reasoning systems “sooner or later” we’ll “stumble upon the benefits of nonviolence” but only if literacy, cities, and long-distance travel emerge first?

When Pinker notes that we can recruit our specialized reasoning modules to tasks that transcend their first-order adaptive function, it seems to me he is merely observing that our native cognitive architecture is not inconsistent with the way we’ve come to use it, otherwise we wouldn’t be using it this way. But that’s trivial.

What is wanted is an explanation of “the appearance” of the really crucial antecedents to the refined cultivation of reason: literacy, cities, long-distance travel and communication, etc. Earlier stages in the ongoing process of the cultivation of reason? How did whatever made this stuff happen, and why did it happen when it did? Pinker does not seem to me to have a good account of this, probably because no one does. But it’s worth pointing out that there’s a good deal of hand-waving at a few critical points in his argument.

I think Pinker fails adequately to acknowledge that capital-‘R’ reason is governed by norms and that these norms are not the same as the implicit rules according to which our native cognitive capacities function. In order to offer a good account of the emergence of capital-R reason, we need to understand the human capacity to acquire and culturally transmit norms. I’m a fan of something like Richerson and Boyd’s account of the adaptive function of a relatively general capacity for cultural learning and transmission, but Pinker never mentions anyone working in this area. And then we need some kind of story about how our native capacity for culturally transmitted norm-acquisition came to be applied to the mind itself, suppressing some cognitive instincts, hyper-developing others, and coordinating various native capacities not “designed” to work in concert, finally resulting in capital-‘R’ reason. Reason is indeed one of mankind’s greatest cultural achievements, but to see it clearly as a cultural achievement leads one to wonder to what extent the historical development of the norms of reason share a common cause with the development of an increasingly humane and pacific moral sensibility.

I’ll add that I thought Pinker was too swift to dismiss the sentimentalist thrust of Jonathan Haidt’s work on moral reasoning and judgment. Reading Better Angels, I got the sense that somewhere in Pinker’s psyche there is a little Chomskyan Cartesian rationalist holding out against the sentimentalism and conventionalism the neo-Darwinian worldview seems to me to imply. My guess is that even the norms of reason are embodied in habits of sentiment.

Lest I convey the sense that I disagree with Pinker more than I do, let me say that Better Angels is a truly magnificent synthesis that takes us a long way to explaining what Pinker has convinced me is the most profound and overlooked phenomenon of human history. I criticize because I love.