Rome: Eternal City of Painting

For its central and seemingly endless role in the history of the Western world, Rome more than earns the nickname of “Eternal City.” For centuries that history has sparked the imaginations of painters around the world hoping to capture some of the magic of the ages. In The History of Rome in Painting, edited by Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Roselyne de Ayala, a team of art historians gathers together the best paintings ever made in tribute to the times of Rome. Working from the central idea that art history can enhance political and social history not only by illustrating events great and small, but also by giving some of the elusive flavor of what it feels to be inspired by the past or the present of Rome, The History of Rome in Painting brings the entire panorama of Rome to life spectacularly as only great painters can.

As Caracciolo explains in her introduction, The History of Rome in Painting is the latest in a series of volumes begun by the late French historian Georges Duby. Duby believed that each of the rebirths of Rome over the millennia matched a rebirth in the “Roman school of painting—an international one, consisting of Roman as well as foreign painters” who have each “written a new chapter of its history,” writes Caracciolo. Following The History of Venice in Painting and The History of Paris in Painting, this volume carries on Duby’s work and may mark the apex of the realization of his vision of a coherent history encompassing both art, faith, and politics. “Style, syntax, and vocabulary may vary, and symbols and dream projections may come to replace allegories” Caracciolo says of the parade of artists processing through the book, “but even as these changes unfold over time, the images retain their power.” On the biggest stage in history, artists have painted a continuously unfolding backdrop to that drama that says as much about Rome as about themselves. The History of Rome in Painting guides you through every act of that drama.

The book begins with the mythic origins of the Roman world, such as the tale of Romulus and Remus as depicted by Rubens, and quickly moves into the legendary age of the Sabine Women and the Oath of the Horatii, both of which David romantically rendered for Neoclassical France on the verge of revolution. It may seem odd that the history begins with artists from centuries later, but the oscillating effect of the near past reflecting on the distant past continually fascinates. When Cesare MaccaripaintsCicero accusing Catiline before the Roman Senate, it’s as much about the ancient government as about the hopes for Italy’s newly founded 19th century version. In showing how the pagan Dea Barberini, a female personification of the late Roman empire itself, evolved visually and philosophically into the Christian Virgin Mary, the book encapsulates whole volumes of history into a powerful, yet simple series of pictures. “In this image we glimpse the roots of Christian dogma as well as the way in which the ancient myth was radically transformed,” the text reads in staggering understatement. Similarly magical tricks of dry history set brilliantly alight by beautiful imagery beautifully chosen fill the book.

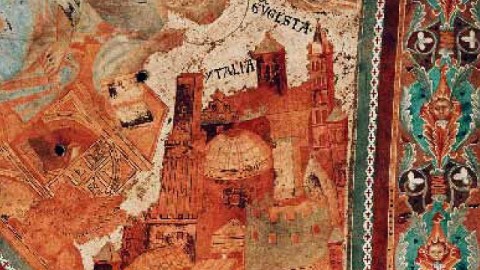

As wonderful as it is to find the landmarks of the Renaissance and other familiar works in the flow of the narrative, what I found most enlightening were the small wonders the team of specialists offered. Tucked in a corner of one of Cimabue’s frescoes in Assisi’s Basilica of San Francisco, we find what may be the first painted cityscape in the history of Western art (shown above). Cimabue’s “Ytalia” provides a bird’s eye view of Rome from the 13th century that also “visual[izes] a political system, with its hierarchy and its vision of history.” In gathering together the Castel Sant’Angelo, Saint Peter’s Basilica, and the Pantheon, Cimabue painted “a political manifesto” showing how the empire of the Caesars now belonged to that of the Popes. It’s amazing that such a small detail could say so much, but almost more amazing how easily it could be overlooked without such a resource as this book.

All the great artists who came to Rome for inspiration find their rightful place here, from the Renaissance masters to Turner to Ingres to Corot to Sargent. The breathless pace of the narrative, matched with the overabundance of three hundred color illustrations, can leave you with a severe case of Stendhal syndrome. And yet I still wished that the final sections of twentieth century art could have slowed down a bit more. Seeing for the first time the expressionist paintings of Mario Mafai depicting the tragic descent of his country into the Fascist nightmare of the Mussolini years left made me wanting more and wondering whom else I have yet to discover.

Freud once mused on Rome as “not a human habitation but a psychical entity with a similarly long and copious past—an entity, that is to say, in which nothing that has once come into existence will have passed away.” This Rome as a state of mind in which the past never passes away exists vibrantly in The History of Rome in Painting. If history could only be taught this colorfully in schools, perhaps we could finally stop repeating the old mistakes. If the eternal question of history is what does it mean to us today, then this visual tribute to the “Eternal City” is a good place to begin looking for answers.

[Image:Cimabue. Saint Mark and Italy/Rome (Ytalia), c. 1280 (detail). Fresco. Basilica of San Francisco, Assisi, Italy.]

[Many thanks to Abbeville Press for providing me with the image above from and a review copy of The History of Rome in Painting, edited by Maria Teresa Caracciolo and Roselyne de Ayala.]