Long Exposure: Looking Back on the Civil War in Photographs

It’s not easy to imagine today in our world of high-speed photography and camera phones what it was like to have your photograph taken in the 19th century. The still very new technology required sitters to remain motionless for long periods—sometimes several minutes—for the image to be captured by the plate. Any movement would blur the image. This year marks the sesquicentennial of the beginning in April 1861 of the American Civil War, the first American armed conflict to be caught on camera. A new exhibition of Civil War photos at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, opens up a family album of sorts to show us the forgotten figures of that conflict—the everyday people unheralded by history books, but who look much more like us today than the larger-than-life leaders we all know by name.

It’s tempting to imagine these people as forever unsmiling wraiths inhabiting a cold, gray world. The difficulty of maintaining a smile for the necessary duration when in front of a camera prevented most people from even trying. (The period’s hit-or-miss dental practice didn’t help either.) They always seem more like statues than people—stern and rigid, as if already dead before the shooting even began. Mathew Brady and other famous photographers of the period usually photographed either living leaders such as Lincoln or Grant or photographed the dead scattered about the battlefields. (Brady actually moved dead soldiers sometimes to choreograph the specific look he wanted.) The Liljenquist Collection recently put on display shows neither leaders nor the dead, but rather the living frozen in time in the photos.

“Have you ever seen a photograph of a person you knew you would never forget? Has a photograph influenced you to change your opinion on an important issue?,” Brandon Liljenquist writes in a wonderful collector’s essay. “For me, a tintype photograph of an American Civil War drummer boy turned out to be such a photograph. This young soldier would reach across time to challenge my beliefs about what makes an army great.” Brandon goes on to explain how seeing a young man about his age facing the prospect of death in battle 150 years ago made him rethink today’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Liljenquist Family, who had been collecting photos from the Civil War period for 15 years, donated over 600 items to the Library of Congress with the wish to create a memorial to the dead of that past that would simultaneously honor the recently fallen. “In the summer of 2009, The Washington Post published deeply moving photos of U.S. servicemen killed in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Brandon continues. “Upon seeing them, [my brother] Jason and I were struck with an idea. We envisioned a way to use our own collection of photos as a Civil War memorial. From our collection, we would select 412 of the best images; 360 Union soldiers (one for every thousand who died), and 52 Confederate (one for every five thousand). Presented together, we hoped the photographs would illustrate the magnitude of our nation’s loss of 620,000 lives in a way never before shown in the history books.”

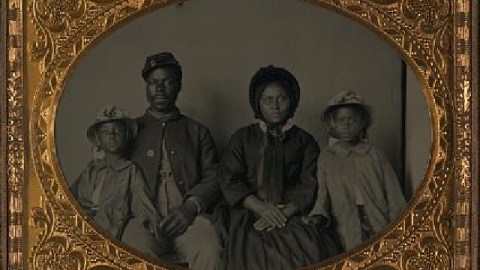

Of all the haunting photographs of the Liljenquist collection, the one that lingered in my memory the longest was a family portrait of an unidentified African-American Union soldier with his wife and two daughters shot sometime between 1863 and 1865 (detail shown above). In that single image you can see everything that man fought for—himself, his country, and his children, who he hoped would live in a brighter future free of prejudice. These photographs humanize the conflict in a way that the history textbooks often fail to do. Just as they were created by long exposure, perhaps it will take long exposure to these photos to burn into our consciousness the humanity on the line whenever our country goes to war.