I Dig That Rock and Roll Music (But What Does It Mean?)

Carl Scott is probably the blogworld’s leading expert on the content of rock music (both words and music). He calls that content, once in a while, its ideological dimension.

Carl both is trained in political philosophy—especially Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America—and actually knows and loves the music. Not only that, he seems to believe in God and America.

I have to admit I’m weak on the musical knowledge. For one reason, I’m tonedeaf or close to it. For another, I’m too old to be keeping up with the latest musical trends.

But I do like “classic rock.” On my car radio (yes, I use the GPS by not the CD player), I rarely mess with NPR. Instead, I listen to an excellent station that plays nothing but the classic tunes of the sixties, seventies, and eighties.

Here’s Carl’s very thoughtful and thought-provoking conclusion:

While rock’s primary ideological element thus is sexual/psychic-al libertarianism, its secondary element, I would argue, is a profound ambivalence about modernity. This often is expressed by opposition to corporate capitalism, but it runs much deeper. Fundamental to the best rock’s “timeliness,” I think, is its disappointment with or even despair over the materially well-provided-for modern life. How to best deal with the supposedly good contemporary life and the conformist temptation to resign ourselves to its satisfactions is one of its basic themes. This is why rock resonates in the enclaves of the prosperous around the globe while it never really catches on with impoverished populations, and a major reason why it came to be identified as a white thing in America. For our (rich and middle-class) generations, the best rock artists serve a similar purpose as the romantic poets did for earlier ones—as the rare souls who glimpse the full implications of modern rationalism for living, and whose art seeks to provide an aesthetic refuge and alternative.

So rock music, at its founding (so to speak), really was about celebrating rocking and rolling against uptight middle-class conformity. That softened into the sexual revolution of the 1960s.

Rock has remained all for those two modes of sexual freedom, to some extent. But sexual liberation is boring these days, because almost everyone is liberated.

But rock has not been about “the working man.” That’s folk music. When Springsteen steps out to whine about Youngstown or embrace Woody Guthrie’s message, he lets us know he’s being more folky than rock. And Joan Baez had to change the words of THE BAND’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” to make it a working man’s song—or not a noble farmer’s rebellion against the first form of Yankee imperialism. Folk music has too often been Northern intellectuals with a very questionable political agenda singing about some imagined working man. To be fair, I wouldn’t put Bruce in that category; early on, he was quite poetic about the working men he actually knew in New Jersey (and he celebrated their romantic longings with a power rarely found in rock).

If my memory serves (or has been enhanced by Jersey Boys), the working man’s band in the early seventies was THE FOUR SEASONS, who didn’t sing about the plight of the guy with the lunch pail. Who wants to party to THAT? I could go on to say something about the greatness of NEIL DIAMOND, but that might not impress a BIG THINK audience.

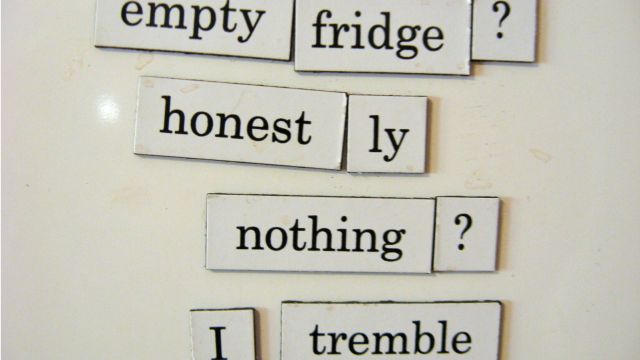

Rock, after its anti-war phase, has been about images of liberation from middle-class productivity, for a kind of amorphous freedom. It’s definitely not been about political revolution, just as it’s not generally been about “social responsibility.” It was sometimes about drugs, but more often has been about dissatisfaction with the limited satisfactions available to members of the white middle class (without employing the remedy of drugs). It’s fairly rarely been about mocking being middle-class (even she’s a small-town girl who’s crazy about Elvis is basically the suburbs mocking the country), but usually it takes the misery (or displaced longings) of living with unprecedented freedom in the midst of prosperity all too seriously.

So the whining is usually ineffectual and readily commodified—a safe form of bohemianism, a Marxist (or libertarian!) might say, for our bourgeois world.

It might be significant that rock rarely follows Tocqueville in seeing being a citizen or being a creature or being a responsible parent as ways out of our lonely emptiness. It might be significant that COUNTRY MUSIC often does.

Why doesn’t he give more examples, you say? Because I might screw them up. I’ll leave them to Carl.