“How could you conceivably cut yourself off from other men and from the life they bring you in such abundance? In the name of what uncaring, ivory-tower kind of attitude?” Pablo Picasso said in a 1944 interview discussing the political nature of much of his painting. “No; painting is not there merely to decorate the walls of flats. It is a means of waging offensive and defensive war against the enemy.” Picasso never felt comfortable with the false neutrality that many other artists espoused in the face of tyranny. Picasso: Peace and Freedom at the Tate Liverpool gathers together the political Picasso and provides a template for all thinking and feeling people on how to wage war artistically, to stand up for what you believe in, and, most importantly, to give peace a chance.

The classic image of Picasso the artist is of Picasso the hedonist, painting, living, and loving as if there were no tomorrow. The sensationalism of the scandalous affairs he left in his infamous wake unfortunately drowns out many of the other aspects of his life. Picasso the tireless advocate of human rights and campaigner for peace emerges in this show after too many years of submersion beneath the popular misconceptions. This exhibition focuses on Picasso’s politicizing between 1944 and 1973, when World War II wound down and the bipolar Cold War world rose up.

For many, Picasso will always have chosen the wrong side of the Cold War in his communist party membership. “My adhesion to the Communist Party is the logical outcome of my whole life,” Picasso remarked in the 1960s. “For I am glad to say that I have never considered painting simply as pleasure giving art, a distraction; I have wanted, by drawing and by colour, since those were my weapons, to penetrate always further forward into the consciousness of the world and of men, so that this understanding may liberate us further each day.” For Picasso, art equaled life. If politics impinged on the freedom of life, then it necessarily limited art. If anything limited art, then Picasso would be there to fight back. In our jaded world today, we’ve lost the idea of art as a life and death concept. Perhaps Picasso can reteach us that truth and not only bring back a vital relevance to art, but also help us liberate our own understanding of the political structures that exert force on our lives and attempt to coerce or control us.

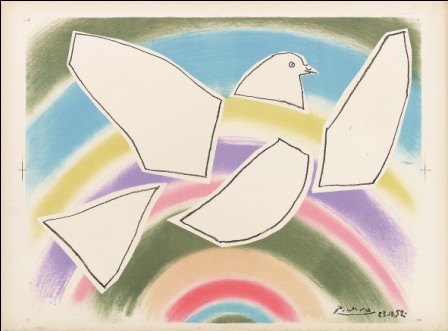

Dove in Flight in Rainbow (pictured), a 1952 lithograph, sweetly conveys a message of peace through fractured simple shapes against a pastel palette. The postwar peace movement adopted Picasso’s Dove of Peace as an emblem of hope and human warmth to combat the chill of the Cold War. Various peace conferences selected Picasso’s dove as their shorthand symbol for the struggle for peace.

Picasso: Peace and Freedom, however, isn’t all doves and pastels. Although Guernica, Picasso’s most powerful antiwar statement, isn’t present, 1944-1945’s The Charnel House more than makes up for the missing masterpiece. At the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis that threatened to end the world in an exchange of warheads, Picasso painted 1962’s The Rape of the Sabine Women, proving that he never lost his touch or stomach for tackling tough subject matter that needed to be addressed by someone. If the most famous artist in the world couldn’t use his fame and power for a greater good, Picasso reasoned, then what good is fame, after all?

“What do you think an artist is?” Picasso once asked, before answering himself. “A half-wit with nothing by eyes if he is a painter, ears if he is a musician, lyres installed on every floor of his head if he is a poet, or just muscles and nothing else if happens to be a boxer? Far, far from it: at the same time he is also a political being, keenly and perpetually aware of the heartbreaking or passionate or delightful things that happen in the world, and he moulds himself entirely in their likeness.” As the reality of perpetual war against a stateless enemy dawns upon Western societies much too late, Picasso’s approach to peace by crossing borders and national ideological lines through the imagination may offer us a solution to the mess we’ve found ourselves in even after such a long commitment of lives and treasure.

Picasso’s question of “What do you think an artist is?” could quite easily be “What do you think a person is?” The answer is the same: a thinking individual struggling to comprehend the incoherence of a violent world. Did the Tate Liverpool really need to amass 150 paintings, prints, sculptures, drawings, and ceramics to analyze the political Picasso? Probably not, but the sheer volume of these works screams of the decibel levels that Picasso achieved through this work in his lifetime. The next question for people today is if they, too, will listen to what Picasso is saying, which may sound like the simple lyrics of a simple pop song, but beneath that simplicity is the complex answer to our complex world today.

[Image: Pablo Picasso. Dove in Flight in Rainbow, 23 October 1952. Lithograph 55.2 x 74.8 cm. Photo © Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, Germany. © Succession Picasso/DACS 2010.]

[Many thanks to the Tate Liverpool, London, for providing me with the image above and press materials for Picasso: Peace and Freedom, through August 30, 2010.]