Celebrity Religion: On Michael Jackson, Princess Diana, and Mother Teresa

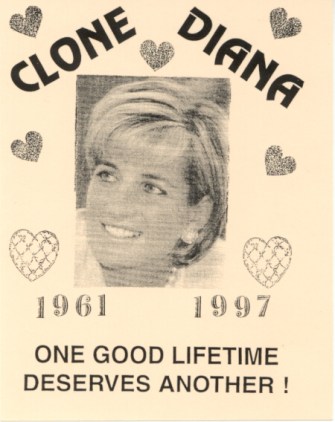

A 1997 poster appearing in Central Park.

Perhaps the best commentary on the cultural reaction to Michael Jackson’s death comes from the NY Times’ columnist Bob Herbert. After describing meeting Jackson in the mid-1980s as one of the “creepier experiences” of his life, Herbert goes on to discuss how Jackson was the perfect symbol of the age, a retreat for Americans into fantasy during the years of the Reagan administration, rising poverty, and an escalating crack and drug epidemic. As Herbert writes:

In many ways we descended as a society into a fantasyland, trying to leave the limits and consequences and obligations of the real world behind. Politicians stopped talking about the poor. We built up staggering amounts of debt and called it an economic boom. We shipped jobs overseas by the millions without ever thinking seriously about how to replace them. We let New Orleans drown.

I had similar thoughts on the eve of Michael Jackson’s death. As I status updated at my page on Facebook: “On a day featuring a historic vote on climate change, everyone is talking about Michael Jackson.”

The reaction to Michael Jackson can only be compared to the media tsunami surrounding the closely paired 1997 deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa. At the time, I was living in my hometown Buffalo, NY and working at the Center for Inquiry before heading off to graduate school two years later. Here’s what I wrote in a 1997 op-ed for the Buffalo News about those events, with obvious parallels to the contemporary Jackson hoopla.

Buffalo News (New York)

October 4, 1997, Saturday, FINAL EDITION

DIANA AND MOTHER TERESA MAY MAKE GOOD FOLK LEGENDS, BUT;

THE TRUTH IS MORE COMPLEX

BYLINE: MATTHEW NISBET –

SECTION: EDITORIAL PAGE, Pg. 2C

LENGTH: 785 words

Where were you when Princess Diana died? I was at a 20-something party where the news passed quickly from person to person. Soon all of us were gathered in front of CNN listening to Tom Cruise, the star of Top Gun, condemn the “stalkerazzi.” To most of those at that party, it was the shocking death of a childhood fairy tale.

When Mother Teresa died, I was at work and got the news almost instantaneously by e-mail. To most people, the passing of Mother Teresa was the death of a contemporary saint.

What followed these two deaths was the greatest heap of mass melodrama, foolishness, faddishness and media hype seen this century. Hundreds of millions tuned in on television, record numbers of magazines were sold, a sea of flowers was created across multiple continents, “Clone Diana!” posters appeared in Central Park, tribute pop songs rode the airwaves. Everyone in the world with access to an antenna was fed image after image of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa.

They were modern-day folk legends that satisfied a global craving, the temptation of humans to believe in the transcendental and mythic. The two were dominant symbols of fading, but still powerful, international belief systems. Princess Diana was the last representative of the elegance, purity and perfection of royalty. Mother Teresa was the dominant image of religious devotion and piety.

Diana’s was a story complete with royal intrigue, infidelity and a winning smile. A pretty and alluring, but not beautiful, girl from an aristocratic background, she enjoyed the one-in-a-billion fortune of marrying the crown prince of Great Britain. From the beginning she knew her duty was to play charming princess and child-bearer to an awkward and staid prince whose heart was elsewhere.

Upon divorce, Princess Diana received a $ 26.5 million-dollar settlement, or $ 600,000 a year. Because she was lonely and depressed, her folk legend asked us to feel sorry for the best-dressed and most photographed woman in history. However, the real tragedy of her life was that she was a mother who left behind two children early in life.

If we peel away the aura of her legend and think critically about her death, we see an all-too-familiar end that goes with a high-risk Hollywood-like lifestyle. The circumstances might be considered akin to the sudden death of a Kurt Cobain or James Dean. With her children in England, Diana was jetting around Europe with her billionaire lover. Whistling through a Paris tunnel in a Mercedes piloted by a drunk driver, playing tag with photographers, she was caught by mortality.

Mother Teresa’s folk legend remains the embodiment of all things saintly. Over the decades her name became a synonym for religious devotion and good samaritanism. But the small woman from Albania was also an implicit representation of turn-of-the-century colonialism. As she tended to the sick and the poor of India, her image administered a necessary antidote to the guilt felt by the Western public over the perceived plight of the Third World.

One of the few members of the media to criticize Mother Teresa is Christopher Hitchens, who writes for Vanity Fair and The Nation. Hitchens questions the use of donated funds by Mother Teresa and their relation to her fundamentalist views against abortion, birth control and divorce. He estimates that she received well over $ 50 million in contributions from individuals, religious organizations, corporations and secular foundations. Yet with all this money, she ran colonial-style health clinics that, according to many former volunteers, did little more than pray for the dying. Many in Calcutta resented her international publicity, claiming she broadcast an unfair image of urban poverty while doing little to work for social reform.

In the end, what do we know of the effectiveness of Mother Teresa’s efforts? We don’t dig into statistics like percentages lifted out of poverty, number of urban health clinics, birth-rate decline or improvement in average incomes and education levels. All we have is the enduring image of a white, frail nun in a sari tending to the dying and sick of India.

The glorification of Princess Diana and Mother Teresa is a testament to the power of the primordial drive to push critical thought aside and to believe in the extraordinary, the magical and the transcendental.

Yes, their lives were marked by significant contributions. But to deify them in death does not appeal to reason.

MATTHEW NISBET is a writer living in Williamsville.