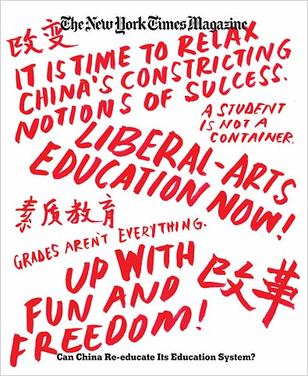

Can the Chinese educational system embrace creativity and innovation?

n

nn

What caught my attention was the fact that the American and Chinese educational systems appear to be going in the opposite directions. While Americans are really getting into rigorous testing and a renewed emphasis on science and math, the Chinese are learning to downplay testing and are emphasizing things like innovation:

“…Some prominent government officials have grown concerned that too manynstudents have become the sort of stressed-out, test-acing drone whonfails to acquire the skills — creativity, flexibility, initiative,nleadership — said to be necessary in the global marketplace. “Studentsnare buried in an endless flood of homework and sit for one mocknentrance exam after another, leaving them with heads swimming and eyesnblurred,” lamented former Vice Premier Li Lanqing in a book describingnhis efforts to address the problem. They arrive at college exhaustednand emerge from it unenlightened — just when the country urgently needsna talented elite of innovators, the word of the hour. A recent reportnfrom the McKinsey consulting firm, “China’s Looming Talent Shortage,”npinpointed the alarming consequences of the country’s so-calledn”stuffed duck” tradition of dry and outdated knowledge transfer:ngraduates lacking “the cultural fit,” language skills and practicalnexperience with teamwork and projects that multinational employers in anglobal era are looking for.

nn

Even as American educators seek to emulate Asian pedagogy — antest-centered ethos and a rigorous focus on math, science andnengineering — Chinese educators are trying to blend a Western emphasisnon critical thinking, versatility and leadership into their ownntraditions. To put it another way, in the peremptorily utopian stylentypical of official Chinese directives (as well as of educationese thenworld over), the nation’s schools must strive “to build citizens’ncharacter in an all-round way, gear their efforts to each and everynstudent, give full scope to students’ ideological, moral, cultural andnscientific potentials and raise their labor skills and physical andnpsychological aptitudes, achieve vibrant student development and runnthemselves with distinction.” Meijie’s rise to star student reflects anmuch-publicized government call to promote “suzhi jiaoyu” — generallyntranslated as “quality education,” and also sometimes as “characterneducation” or “all-round character education.” Her story also raisesnimportant questions about the state’s effort, which has been morengenerously backed by rhetoric than by money. The goal of change is tonliberate students to pursue more fulfilling paths in a country wherenjobs are no longer assigned; it is also to produce the sort of flexiblynskilled work force that best fits an international knowledge economy.”

[image: New York Times Magazine]

n