America’s Fragile Recovery

Recently I wrote about a McKinsey Global Institute study that found the American economy is likely to stay slow in the long term as a larger percentage of its population leaves the workforce and retires. While the economy has begun growing again and the unemployment rate has finally come down below 9%, the American economy’s short-term prospects also aren’t very good.

Labor force participation—the percent of Americans 16 and over who are working—which passed 67% in the mid-90s, has dropped to nearly 64%. That’s the lowest level since 1984, before large numbers of women had entered the workforce. That’s partly because of the increasingly large portion of the population that has retired, and partly because the economy simply hasn’t been adding enough jobs to keep up with growth in the working age population. On average economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal don’t think the country will return to full employment until 2015, and expect the unemployment rate to be 7.7% when President Obama comes up for reelection in 2012. That would be a significant improvement, but still the highest rate since Ford lost to Carter in 1976.

As Robert Reich points out, the fragile economy is suffering new shocks. Unrest in the Middle East—particularly now in Libya and Bahrain—helped oil prices reach a 29-month high earlier this month. Bad harvests combined with a long-term rise in demand have driven food prices up. The devastating earthquake in Japan—the world’s third largest economy—sent the Nikkei tumbling more than 10% in a week. All these things are likely to slow the global economy, and have a huge impact on the millions of Americans who are already struggling.

They are also likely to exacerbate our very real fiscal problems. But, as I wrote recently, while we can’t continue to spend more than we earn for that much longer, we aren’t actually on the verge of bankruptcy, and now may not be the time to cut government programs or slash employee salaries. Instead, we may need more stimulus, either in the form of targeted tax breaks or greater spending, because our debt problem—and every other problem—will be much more serious if the recovery stalls.

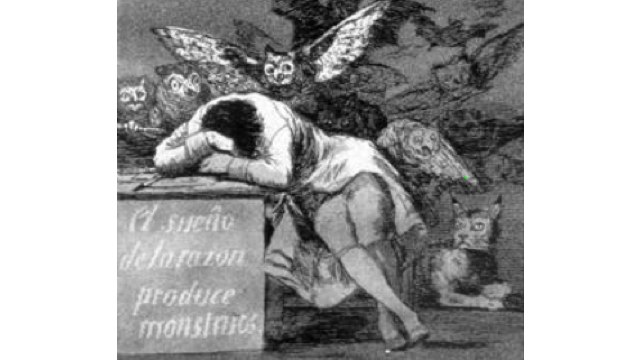

Photo credit: Albert Duce