THE KING’S SPEECH vs. THE SOCIAL NETWORK

There have been a lot of words trying to explain why the Academy chose the last noteworthy King of England over the founder of Facebook. Here’s one explanation:

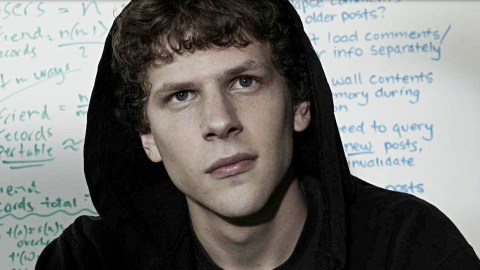

“The King’s Speech” is an anesthetic movie, “The Social Network” an invigorating one—and their scripts’ departures from the historical record serve utterly divergent purposes. The tale of royal triumph through a commoner’s efforts expurgates the story in order to render its characters more sympathetic, whereas the depiction of Mark Zuckerberg as a lonely and friendless genius (when, in fact, he has long been in a relationship with one woman) serves the opposite purpose: to render him more ambiguous, to challenge the audience to overcome antipathy for a character twice damned, by reasonable women, as an “asshole.”

Actually, the Facebook founder (Zuckerberg) is described at the film’s end as a guy who wants to be an asshole; he lacks the guts even to achieve that low but often memorable goal.

“The King’s Speech” is actually aristocratic history; the hero is made better or more noble than he really was through highlighting his singular greatness or admirable individuality. It’s true he’s no ordinary aristocratic hero insofar as he has to struggle so hard to be a king in almost the most minimalist conceivable sense. He doesn’t rule his people, but only reads speeches written by others to bolster their morale. In doing so, however, he performed a perhaps indispensable if minor role in wining a war that saved not only his country but perhaps civilization itself. There’s more than a trace of magnanimity in this rather unexeptional (certainly not brilliant) family guy with un-heroic self-esteem issues.

Getting an audience to appreciate nobility requires highlighting it, especially in this case. In this case, members of the audience have to come to appreciate the heroic dimension of the king’s struggle to do what almost every one of them could have done fairly effortlessly and probably better.

It’s hard to see why the film’s portrayal of the Facebook founder can be called ambiguous. It’s not surprising that in real life he’s better with “relationships” than he is in the movie. Who isn’t? Probably almost everyone in the audience is. The point of the film is, surely, that those who pass for heroes these days–those at the top of our meritocracy defined largely by productivity–display none of the virtues of the heroes of the past, and even none of the virtues displayed by ordinary people–such as ordinary family guys in stable marriages (the hapless but loving and faithful enough husbands and dads we see in “Hall Pass” are, in the decisive respects, paragons of virtue by comparison to most of the characters in “The Social Network”).

By the standard of heroic virtue, the old hereditary aristocracy looks much better than our democratic meritocracy. It’s the characters in “The Social Network” who lack real vigor; their lives–despite all the techno-innovation and the creation of billions of online friendships–seem diverted from everyting genuinely important or deeply animating in human life. Compared to the stuttering king, they’re wimps. They don’t exhibit any magnanimity or greatness of soul.

Here’s one astute account of how the Facebook founder looked to many people in the audience:

In The Social Network, a socially inept computer geek becomes an accidental billionaire making many enemies along the way. It was a brilliantly scripted story, but we don’t really care much about the fate of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg); indeed, we probably feel that all those billions in the bank have provided an enviably comfortable cushion against the vicissitudes he’s faced.