The Joys of Sex, Springtime, and the Song of Songs

It’s a wonderful oddity—I hesitate to say “coincidence”—that the best erotic poem in literary history should appear smack dab in the middle of the Bible. The Song of Songs (known also as the Song of Solomon or Canticle of Canticles) is an ancient Hebrew text of uncertain date; some scholars trace its origins to 900 BCE, while others argue for a composition as late as the Hellenistic period, around the third century BCE. Its traditional attribution to Solomon is almost certainly apocryphal: its author may have been a court poet or a commoner, a man or a woman, one person or several.

The one certainty I’ve offered above—that it is an erotic poem—flies in the face of centuries’ worth of clerical commentary, which has doggedly sought in it an allegory of spiritual love. Yet the sexy interpretation is now the dominant one among critics, as it has long been the intuition of the common reader. In his foreword to Chana and Ariel Bloch’s 1995 translation, Stephen Mitchell dryly remarks that “the allegorical interpretation of the Song, which dominated both the Jewish and Christian traditions for almost two thousand years…qualifies as one of the more peculiar achievements of the human mind.” He adds that “the young men who sang it in the first-century taverns of Jerusalem…were better readers than the allegory-dazed scholars and priests.”

A quick glance at the text will prove him right:

My beloved put in his hand by the hole of the door, and my bowels were moved for him.

I rose up to open to my beloved; and my hands dropped with myrrh, and my fingers with sweet smelling myrrh, upon the handles of the lock. [Song of Sol. 5:4–5, KJV]

This passage, which means exactly what you think it does, has inspired centuries of hilariously clean-minded exegesis, such as this gloss from Matthew Henry’s 1706 Concise Commentary:

He put in his hand to unbolt the door, as one weary of waiting. This betokens a work of the Spirit upon the soul. The believer’s rising above self-indulgence, seeking by prayer for the consolations of Christ, and to remove every hinderance to communion with him; these actings of the soul are represented by the hands dropping sweet-smelling myrrh upon the handles of the locks. But the Beloved was gone! By absenting himself, Christ will teach his people to value his gracious visits more highly.

Still, the Song has much more to offer than Sunday-school snickers. Among the great beauties of the work are its similes, which participate in a rich allusive tradition but strike the modern ear as wildly improbable, almost phantasmagorical:

Behold, thou art fair, my love; behold, thou art fair; thou hast doves’ eyes within thy locks: thy hair is as a flock of goats, that appear from mount Gilead.

Thy teeth are like a flock of sheep that are even shorn, which came up from the washing; whereof every one bear twins, and none is barren among them.

Thy lips are like a thread of scarlet, and thy speech is comely: thy temples are like a piece of a pomegranate within thy locks. [Song of Sol. 4:1–3, KJV]

You sense that the two lovers singing the Song are vying to outdo each other in praise, as Romeo and Juliet would in a later era. They are enjoying the play of their minds as well as their bodies, which they explore in illicit garden trysts at night.

Gorgeously hewn as the King James version is, it underplays the eroticism slightly, as in 6:12, which it translates as “Or ever I was aware, my soul made me like the chariots of Amminadib.” The Blochs render this same line as:

And oh! before I was aware, she sat me in the most lavish of chariots.

If this seems like unusually forward behavior for a Biblical woman, that’s because it is. In a book not widely noted for its contributions to feminism, the Song stands out as a tribute to female power and glory:

Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners?

There’s a sense, in fact, in which the Song is a counterstatement to the whole rest of the Bible, a breath of spiced wind through the harsh panorama of sanctimony and suffering. The lovers are the only Biblical characters I can think of who flout authority and are not punished, whose disobedience is actually celebrated. “The lovers discover in themselves an Eden,” the Blochs write in their introduction, and Mitchell touchingly affirms that “there is no sin in this garden, no knowledge of good and evil. Everything is innocence and fulfillment.” Eavesdropping on the lovers’ pleasure, you feel the clock turning back on several millennia of neurosis.

Yet the poem is not all sweetness, nor is its innocence naiveté. In the closing verses the young Shulamite woman issues her great commandment, half plea and half warning, to the man she loves:

6: Set me as a seal upon thine heart, as a seal upon thine arm: for love is strong as death; jealousy is cruel as the grave: the coals thereof are coals of fire, which hath a most vehement flame.

7: Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it: if a man would give all the substance of his house for love, it would utterly be contemned.

In spirit this anticipates Juliet’s “swear not by the moon, th’inconstant moon,” and as a character the Shulamite is not unlike Juliet: very young, very deeply in love, but nobody’s fool. Ostensibly she shouldn’t know much about jealousy, let alone death, but the wisdom of Solomon speaks through her, and the hard truths she utters bind like a covenant.

It remains a mystery as to how a poem so ardently secular found its way into the Bible at all. Mitchell asks bluntly, “What were the ancient rabbis thinking?” I’d like to believe they weren’t as crazy, or innocent, as they might appear. There is something sacred about young love—sex and all—which the Song has communicated better than anything since. I like to think the ancient rabbis wanted to expurgate the poem, but had the wisdom to act against their better judgment. Their decision speaks finally to the deep humanness of the Bible.

Why not celebrate humanness yourself in the coming weeks, by reading the Song as a rite of spring? It’s already a traditional Passover text, but regardless of your faith or lack thereof, it’s the ideal accompaniment to wine-drinking, flirtation, outdoor lovemaking, drives in the countryside, and just about anything else that makes warm weather preferable to cold and being in love a hell of a lot better than being dead.

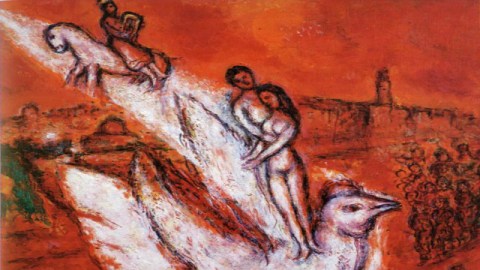

Image: Detail from Song of Songs (1974), by Marc Chagall