Should We Be Letting Machines See for Us?

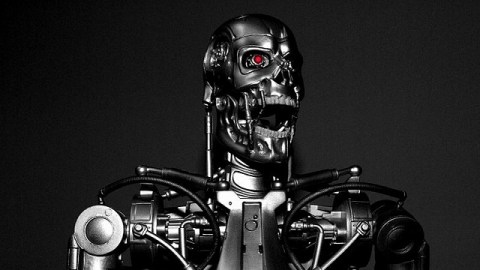

Anyone who has seen James Cameron’s 1984 film The Terminator remembers “seeing” through the eyes of the killer android sent into the past as it scans its surroundings for clothes, weapons, and, eventually, its target. Beneath the fleshly form of the future “Governator” resided a robot skeleton sent from the future to eliminate the main human foe of the machines’ plan to rule the future. German filmmaker Harun Farocki would later call those pictures “operational images”—the machine-made and machine-used pictures of the world that threatened to supplant not just how people see, but people period. In the November 2014 issue of the journal e-flux, Trevor Paglen revisits Farocki’s now-decade-old work and updates it for today. Paglen raises interesting questions about the very nature of how machines see as well as whether we should be letting machines—from license plate readers at intersections to drones in combat zones—see for us.

Paglen begins by pointing out just how visionary Farocki’s early studies were. “Harun Farocki was one of the first to notice that image-making machines and algorithms were poised to inaugurate a new visual regime,” Paglen argues. “Instead of simply representing things in the world, the machines and their images were starting to ‘do’ things in the world. In fields from marketing to warfare, human eyes were becoming anachronistic.” Knowing that machines operate more efficiently than humans ever can, we’ve ever more increasingly outsourced the watching of our world. More significantly, not only were we letting the machines see for us more and more, but we were also letting those same machines act upon what they saw in ways never before imagined.

Paglen cites specifically Farocki’s films Eye/Machine I, II, and III and how in them Farocki “thought these bits of visual military-industrial-complex detritus were worth paying much attention to.” (A clip from Eye/Machine III can be seen here.) In the Eye/Machine films, Farocki shows how computerized vision systems track (and target) moving objects (sometimes for termination). Paglen confesses to initial confusion over Farocki’s fascination with these images before realizing they were just another part of Farocki’s career-long “method [of] look[ing] into the dark and invisible places where images get made.” For Farocki, the fact that the War on Terror was waged remotely through the “eyes” of drones and satellites threw into question who was really “calling the shots”—the machines visualizing and assessing the situation or the human pressing the “go” button based on those pictures.

Realizing that a decade is an eternity in terms of modern technology, Paglen decided to revisit Farocki’s obsession with “operational images.” Paglen first realized that today’s images are mostly “images made by machines for other machines,” with little human intervention once the systems are in place, leaving “Farocki’s dramatic exploration of the emerging world of operational images now anachrononistic.” The visualizing rise of the machines (to borrow a Terminator sequel title) is already here.

Farocki’s “operational images” idea isn’t just anachronistic in Paglen’s eyes; it’s also never been true. “In retrospect, there’s a kind of irony in Farocki’s Eye/Machine,” Paglen explains. “Farocki’s film is not actually a film composed of operational images. It’s a film composed of operational images that have been configured by machines to be interpretable by humans. Machines don’t need funny animated yellow arrows and green boxes in grainy video footage to calculate trajectories or recognize moving bodies and objects. Those marks are for the benefit of humans—they’re meant to show humans how a machine is seeing.” James Cameron gave his Terminator a point of view because we the human viewers—not the machine—needed one.

In a way, we’ve been fooling ourselves by designing machines that provide images for our benefit that the machines themselves don’t need. As Paglen found out in his research on today’s “operational images,” “machines rarely even bother making the meat-eye interpretable versions of their operational images that we saw in Eye/Machine. There’s really no point. Meat-eyes are far too inefficient to see what’s going on anyway.” Today we put our literally blind trust in machines more and more “even as they’re ubiquitous and sculpting physical reality in ever more dramatic ways,” Paglen points out.

“We’ve long known that images can kill. What’s new is that nowadays, they have their fingers on the trigger,” Paglen chillingly concludes. Yes, a human builds the drone and a human presses the button that commands the drone to kill, but that same commanding human follows the information fed to him from the machine itself, whether transformed into Faroki’s humanized, “meat-eye interpretable” “operational images” or left as computerized raw data, virtually invisible to human eyes and, possibly, humanizing judgment.

Should we be expecting Terminators to materialize around us with their hidden “operational images” looking to end us? Probably not. But this shift in the how images are made and how we are shaped by them is just as troubling. Paglen doubts there is any way back where we “learn to see this world of invisible images that pull reality’s levers.” However, he calls on “other artists to pick up where Farocki [who died in July 2014] left off, lest we plunge even further into the darkness of a world whose images remain invisible, yet control us in ever-more profound ways.” In a world in which images are more prevalent and powerful than ever before in human history, knowing that we’re controlling how those images are used and how they might be using us is more important than ever.

[Image Source:Wikipedia Commons.]