Is Life Fair?

At the moment, my social media feeds border on conspiracy theory—not a surprise though; these days it is prolific. Remember when Hillary Clinton’s supporters were foaming vitriol in their disdain of Bernie Sanders’s refusal to acquiesce? Then remember when his side felt a different kind of burn, railing against the Democratic National Committee, the Associated Press, and any other organization that might have played a role in his defeat.

To be fair, nuanced conversation is plentiful. For every five intelligent comments, though, at least one clocks in on a “truther” level. After I posted what I felt to be a balanced piece by Glenn Greenwald, I was called a ‘dirty republican,’ that Hillary is a ‘gross, gross person,’ and that Bigfoot is real. I believe the last one was sarcasm, though at this point I can’t be sure.

Fairness is the concept circulating even if the word is rarely spoken. Clinton put in the work and won not only the popular vote, but the larger percentage of superdelegates as well. It’s not fair that Sanders won’t unite the Democratic Party. Or: the game was rigged from the outset. Sanders was never given a fair shake.

Both of these arguments are valid, depending on your point of view—which, apparently, is why nuanced conversation is so challenging when everyone has a voice. Your POV becomes the only one worth contemplating, in your eyes at least. Questions of fairness far exceed this presidential cycle. They seem part of our DNA.

The root of Sanders’s message: corporate greed and bought politicians formed the unfair union now governing America. This notion resonates with a large portion of the populace. That’s because most people believe they deserve what they get, and that others abide by the same rule. The same argument holds true for Trump supporters: we work hard; we’re not winning. It isn’t fair.

As Matthew Hutson writes in the Atlantic, fairness is often tied to magical thinking. Many, in fact, treat the notion of karma like this. Do something good, it returns three-fold. Be greedy, or dishonest, or deceptive, and that too boomerangs back. Yet this philosophy simply isn’t true. Evil people live out their lives in relative peace, while compassionate and caring people die in horrific accidents. The planet doesn’t care about our desires and dreams. It just spins.

Hutson offers research as evidence. Job seekers feel more optimistic about landing a gig after they donate to charity. After the devastating 2008 earthquake in China, those who lost family and friends were likely to believe the ‘universe was unfair.’ Add some distance, however, and people had less problem thinking those ninety thousand deaths were deserved. Unsurprisingly, however, those people are less likely to suffer from depression and anxiety. Beliefs might not be true, but they are comforting.

Many examples of fairness are relatively benign. Others are not. Hutson cites rather disturbing research: “One study found that women who believe strongly that the world is fair are more likely than other women to blame the victim of a hypothetical stranger rape.”

This mindset creates biases, as evidence by another study showing employers to be less likely to hire someone that was laid off. There must be a reason they were fired: they deserved it. It’s easy to see how this feeds a vicious cycle, wherein you find yourself unemployable because all prospective employers feel the same.

And then, of course, there’s the ‘blessing in disguise’ argument: bad things happen to good people because, really, the bad thing is only leading to an even better thing. Optimistic, certainly, though also a function of our inability to accept randomness and bad luck.

Luck is a four-letter word to those who trust in a fair and just universe—even applying that term when landing a job or winning the lottery (the universe loves me!) shows how highly we think of ourselves. Everything is for our benefit, even the supposedly ‘bad’ things, those purposeful obstacles. Sadly, in this light, everything leads to suffering. If the better thing never comes, or is delayed too long, we fall into a funk.

Our brains hate gaps in any story. Unknown and unknowable reasons are excruciating; we create narratives to fill in the gaps. We’ll even overlook the actual reason if the one concocted by our imagination sounds better. Like religion, this invented balancing of the scales does make a difference: it makes us feel better and more confident regardless of the reality of our speculation.

And there is value in that—to us. The problem is other people lose out by our ignorance, witnessing a world lorded over by invented karma police. As Hutson concludes, “No, life’s not fair. And in a cruel twist, our wish to see it as fair keeps us from making it so.”

—

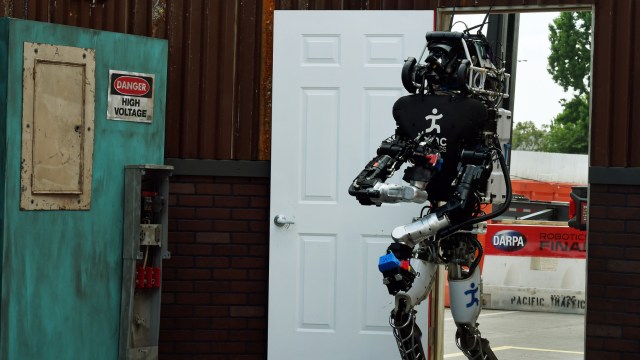

Image: Scott Olson / Getty Images

Derek Beres is a Los-Angeles based author, music producer, and yoga/fitness instructor at Equinox Fitness. Stay in touch @derekberes.