Facing African-American History Through African-American Art

When the Philadelphia Museum of Art purchased Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting The Annunciation in 1899, they became the first American museum to acquire a work by an African-American artist. That purchase announced a new era of recognition of African-American art and artists just as much as the painting itself announced a new style of art moving away from stereotypical “black” scenes towards a freedom of aesthetic choice. Persons of color could express themselves in any way, even abstraction, but faced the new problem of remaining true to themselves at the same time. The new exhibition Represent: 200 Years of African American Art and accompanying catalogue show how these artists faced the challenges posed to them by art and society and provide all of us with a fascinating guide to facing African-American history—tragic, tenacious, transcendent—through its art.

The PMA’s unique among American art museums in its long-standing relationship to African-American creators reaching literally down to its very foundations. African-American architect Julian Abele contributed to the initial design of the museum. (Abele’s masterful drawings of the museum to be greet you in the hallway outside the exhibition space.) But even before Abele’s drawings and Tanner’s Annunciation, PMA curator Edwin AtLee Barber studied and collected the distinctive and enigmatic “face jugs” created by South Carolinian craftsmen who were slaves or former slaves. Barber’s “face jugs” entered the museum’s collection after his death in 1917 and still puzzle experts who see them as water coolers, grave markers, or echoes of African art traditions.

Few African-American works entered the collection until 1941, when art by Philadelphia area artists Horace Pippin, Dox Thrash, and Raymond Steth ignited greater interest in African-American art, thus reflecting the changing times and changing demographics of the Northeastern United States after the “Great Migration” of African Americans from the South. In 1970, after the social turmoil of the 1960s, the PMA purchased native son Barkley Hendricks’ Miss T, a pensive portrait of his then girlfriend Robin Tyler in black dashiki with a full, Angela Davis-esque Afro—a realistic portrait, yes, but also a visual political statement whose controversial nature the museum embraced. Five years later, Seahorses by Sam Gilliam became the first solo show of an African-American artist in the museum’s history.

Today, thanks to the PMA’s African American Collections Committee (founded in 2001) and the museum’s commitment to serving the needs of the region, the museum owns more than 750 works of art representing over 200 African-American artists. To document this collection and to serve as an introduction to African-American art itself, the museum decided to create a special catalogue, the publication of which is celebrated by the exhibition, which presents a tantalizing selection of just one tenth of the overall African-American collection culled from a select 50 artists ranging from 19th century artists Moses Williams and David Drake (aka, “Dave the Potter” or “Dave the Slave”) to still-living, still-working artists such as Kara Walker, Glenn Ligon, and Moe Brooker.

Dr. Richard J. Powell introduces the catalogue with the metaphor of African-American artists “walking on water” in achieving a miraculous balance between individual self-expression and the collective African-American experience. Rather than accept the “facile retreat into epidermalization and the sociological realities of blackness,” Powell’s ideal African-American artists “take up instead the more difficult processes of introspection and dream-work around race, culture, and identity.” True African-American art is, quite literally, more than skin deep, challengingly digging down to the roots of race as a social construction based on power and control, not on melanin and biology.

Consulting Curator of the exhibition and the catalogue’s main author Dr. Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw follows Powell’s thematic lead with a whirlwind, intertwined tour of African-American social and art history that not only introduces the PMA’s collection specifically and the African-American experience generally, but also provides a perfect primer on a post-modern approach to history for the non-academic uninitiated. If you’ve ever been confused by the concept of a “post-racial America,” this catalogue will clear it up. Represent is not about an America that no longer sees race, but instead about an America that sees race for what it truly is—a lie told and retold to divide rather than unite.

Combined, the catalogue and exhibition are eye openers. They bridge the distance between the Gee’s Bend quilters and modern fashion designers such as Patrick Kelly and Stephen Burrows to show a continuum of expression stretching across the loom of time. They re-label the labels of “outsider artist” or “folk artist” as art history ghettoization from mainstream fine arts. Self-taught artists denied training because of race and/or economics such as Bill Traylor, Minnie Evans, Joseph Yoakum, and others finally leap from the “blackstream” to the mainstream. Standing before Bill Thompson’s 1961 painting Deposition, which combines Renaissance religious content with modern style, you can’t help but notice on the wall text his death at 29 years of age and wonder how much more he could have done. Then you wonder how much more so many other African-American artists could have done over the centuries had they been given the chance.

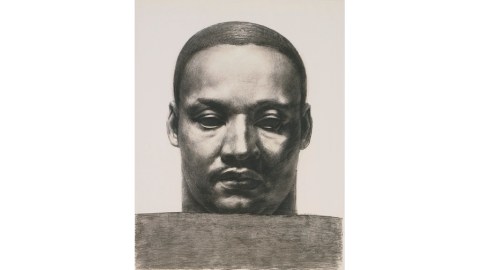

The one work from Represent that represents the goal of the catalogue and exhibition best for me is John Woodrow Wilson’s Martin Luther King, Jr. (shown above), a charcoal drawing for a commission for a MLK memorial in Buffalo, New York. Wilson transforms the literal, physical being of MLK into a symbolic, spiritual work of art—a massive head for a massive intellect that hoped to change minds then and inspires others with that same hope today. “What is required for a work of art to enter the cerebral or soulful realms of the black subject is the act of embodiment,” Powell asserts, “with the artist functioning as a barometer of the shifting cultural indices of gender, class, race, and other social constructs and, only then, responding in kind.” Just as Wilson embodies in Powell’s sense King’s essence, Represent: 200 Years of African American Art embodies what African-American art should be—a mirror reflecting the past, illuminating the present, and forcing us to face the future together.

[Image:Martin Luther King, Jr., 1981, by John Woodrow Wilson (Philadelphia Museum of Art: 125th Anniversary Acquisition. Purchased with funds contributed by the Young Friends of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Museum and in celebration of African American art, 2000-34-1) © John Wilson/Licensed by VAGA, New York.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with the image above and other press materials for, for a review copy of the catalogue to, and for inviting me to the press preview for the exhibition Represent: 200 Years of African American Art, which runs through April 5, 2015.]