DMT makes your brain think it’s dying—and it’s completely wonderful

Back in the mid-nineties, I read a first-person article about the near-death experience (NDE) one curious traveler braved under the influence of ayahuasca while visiting the jungles of Brazil. The potent brew, which requires plants featuring the psychoactive compound dimethyltryptamine (DMT) as well as plants that provide alkaloids to elongate the hallucinogenic effects, has been ritualistically used for, well, “a long time” is the best guess anyone can muster.

While memory is notoriously spotty, I specifically recall the writer lying down on the jungle dirt and watching his body from the forest canopy. Though disassociated, there was no fear. There might have been something about astral traveling; the fact that he had an NDE and returned, refreshed and reinvigorated, stayed with me.

During my three experiences with ayahuasca (and numerous encounters with the isolated DMT; the effects only last a few minutes), I’ve had a similar experience on one occasion. The boundaries of my body felt porous; the distance between myself and my environment dissolved. I also spent a few years working as the music supervisor for the documentary film, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, watching the original four-plus hour cut. NDEs were the most common anecdote offered by those under the spell of this “plant medicine.”

Beyond anecdotes, I’ve never vouched for the metaphysics of the substance. It offers an opportunity to dive deeply into my own psychology and contemplate my habitual patterns. The “healing,” to me, is confronting patterns I’d rather abandon; the ritual is a powerful reminder of why I should. There’s something special about the dissolution of perceived boundaries that anyone can draw benefit from. Treating the “death” metaphorically can serve as a catalyst for real-world transformation.

A new study, published in the journal, Frontiers in Psychology, confirms that the NDE is a universal trait of DMT. A team of researchers from Imperial College London, supervised by one of the world’s leading researchers in psychedelic studies, Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, injected 13 healthy volunteers with either a compound of DMT or a placebo. They then asked 16 questions, comparing their responses to those preferred by 67 medical patients who had experienced NDEs during a heart attack.

A universal experience not limited to psychedelics, the NDE is defined, in part, by “feelings of inner-peace, out-of-body experiences, traveling through a dark region or ‘void’ (commonly associated with a tunnel), visions of a bright light, entering into an unearthly ‘other realm’ and communicating with sentient ‘beings.’”

Elves, specifically. People on DMT see elves.

Chris Timmerman, a PhD candidate in Carhart-Harris’s Psychedelic Research Group and lead author of the study, summates the results:

Our findings show a striking similarity between the types of experiences people are having when they take DMT and people who have reported a near-death experience.

Before analogies drawn from sensations after ingesting an entheogen and those from a heart attack are entwined, the authors offer caution. DMT, they write, is like entering an “unearthly realm,” while actually nearly dying makes you feel like you’re approaching “a point of no return.” Context matters.

That said, Carhart-Harris, who was featured prominently in Michael Pollan’s recent book about psychedelics (discussing how they can help terminally ill patients confront death) notes DMT’s therapeutic utility:

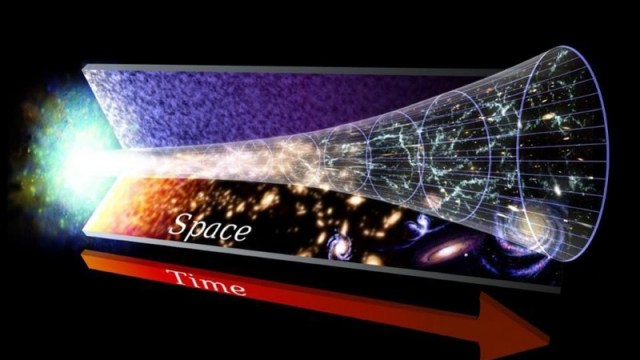

These findings are important as they remind us that NDE occur because of significant changes in the way the brain is working, not because of something beyond the brain. DMT is a remarkable tool that can enable us to study and thus better understand the psychology and biology of dying.

Pollan makes a similar point in his book. We often limit medicine to biological specificity. If I have a headache and a pill decreases inflammation associated with it, it “works.” If I have a heartache, am depressed, or am confronting terminal illness, the perspective given by psychedelics has not been treated as equally valid medicine. But it is, as this and other research is confirming. If the goal is healing someone in distress, be it physically or emotionally, all options should be on the table.

As for the common occurrence of seeing little elves after ingesting DMT—I have not, though people I’ve been in a ceremony with have; the most I’ve “seen” is intense fractal patterns playing off of candlelight—the brain is a wonderful and mysterious machine. Dr. David Luke, a senior psychologist at Greenwich University that specializes in consciousness studies and psychedelics, believes that DMT might hold a key to understanding human spirituality.

DMT is naturally produced in the human body (as well as in other mammals). It has been found in our lungs and eyes and, Luke mentions, appear to play a role in our immune system. The popular citation of DMT being produced in our pineal gland, which has led thousands of cosmonauts to speculate that our “third eye” produces the mystical DMT, is currently unfounded. It could be produced there, Luke says—trace amounts have been found in the pineal glands of rats—but research has not confirmed this. As Luke says:

There is possibility but we have yet to discover what the pineal glands’ actually function is. It seems to be important as a neurological transmitter on certain, little understood, neurotransmitter sites in the brain … But the question remains why we have an extremely potent psychedelic chemical floating around in the human body. Can this account for spontaneous mythical and spiritual experiences?

Could be. But as Timmerman concludes about his study, what’s really essential is DTM’s therapeutic utility. In this light, research is holding up.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Facebook and Twitter.