Angel Eyes: Allen Ginsberg’s Photography at the NGA

The established poet William Carlos Williams wrote in 1956 of newcomer poet (and friend) Allen Ginsberg that he “sees with the eyes of the angels.” Williams most likely referred to the visual aspects of Ginsberg’s poetry, especially the groundbreaking poem Howl, the epic poem that helped define the epoch of the Beat Generation. Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, currently at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, through September 6, 2010, shows how Ginsberg’s photography also demonstrates how his “angel eyes” helped inform the literary movement it as well as document the Beats during their glory days all the way up to the final ones.

Ginsberg began taking photographs in late 1940s. During the peak years of the Beats, from 1953 to 1963, Ginsberg took photos of friends and lovers such as Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Neal Cassady, Gary Snyder, and Peter Orlovsky. These photos comprise nothing less than a family album of the Beat Generation, who stepped outside the conventionality of Eisenhower’s America into nothingness and, luckily, found each other to share the nothing. Ginsberg stopped taking photographs in 1963 for a variety of reasons. That year of the Kennedy Assassination marked in many ways the end of one era and the true beginning of the 1960s in spirit, if not chronology. Ginsberg’s photos languished in a desk until the 1980s, when photographers Berenice Abbott and Robert Frank saw them and encouraged Ginsberg to publish them. Until his death in 1997, Ginsberg continued to photograph, coming to see that medium as complementary to his poetry, going so far as to lecture on “Snapshot Poetics.” Dire financial straits may have initially spurred Ginsberg to publish his photographs, but he finally came to a realization that his vision was both poetic and photographic.

Sarah Greenough, curator of the exhibition and author of the catalogue essay,”Seeing with the Eyes of Angels,” masterfully summarizes Ginsberg’s life and work and neatly fits the photography into the familiar story. She traces Ginsberg’s development as a visual artist through a series of influences. A 1947 class with Meyer Schapiro at Columbia exposed Ginsberg to Cezanne’s experiments with perception. Sent to the MoMA to study the Cezannes there, Ginsberg experienced a “cosmic sensation” he never forgot. Later, Ginsberg hallucinated that artist-poet William Blake revealed to him the interconnectedness of all things. William Carlos Williams taught Ginsberg there are “no ideas but in things” and to make poems more concrete. Finally, Kerouac’s writing, especially his “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose,” Greenough writes, impressed on Ginsberg the power of “an unfiltered prose that focused intensely on an image at a specific moment in time,… a ‘bookmovie… the movie in words, the visual American form.’” Together, these close encounters with artistic heroes gelled together in Ginsberg’s consciousness and drove him to take the stunning photographs in this exhibition.

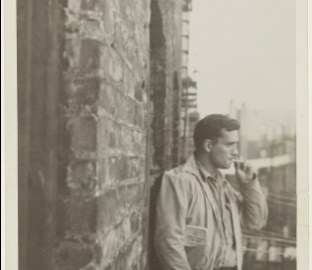

Although Ginsberg spoke of his “Snapshot Poetics,” these are much more than simple snapshots of friends. Ginsberg lived in the moment and tried to give unfiltered experience in his poetry and pictures, but those angelic eyes of his repeatedly chose those magical moments that reveal so much about a person. A 1953 photo of Kerouac standing in the cold (shown) captures both the cool and the isolation of the man. To memorialize a 1956 trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Ginsberg photographed the ancient-even-when-young William Burroughs standing beside a “brother Sphinx.” Long after the Beats had faded from the spotlight, Ginsberg captured Peter Orlovsky at James Joyce’s Zurich grave in 1980, brushing snow from the head of the writer’s statue. Each photograph is an epiphany. Seen together, works such as Ginsberg’s nude self-portraits in youth and age give the full measure of the Beat Generation and not just its brief time of glory.

If you’re a literature junkie like me (not to be confused with Burroughs’ Junkie), then Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg is perfect for you. Seeing the Beats in action brings their lively writing—so grounded in a self-generated and self-preserving cult of personality—even more to life. Seeing Ginsberg’s approach to photography, however, raises his visual art almost to the level of his verbal art. “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,” Ginsberg famously wrote in his beginning to Howl. This exhibition captures that madness but restores those “best minds,” especially Ginsberg’s, to their proper place in American culture.

[Image: Allen Ginsberg. Jack Kerouac, 1953. Gelatin silver print. Image: 15.2 x 10.2 cm (6 x 4 in.). Sheet: 16.2 x 11.2 cm (6 3/8 x 4 7/16 in.). Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. © Copyright 2010 The Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved.]

[Many thanks to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, for providing me with the image above and a review copy of the catalogue to Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, which runs through September 6, 2010.]