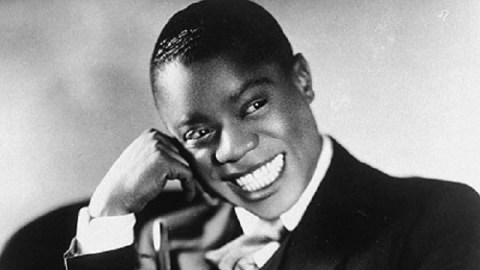

Was Louis Armstrong the First Great American Modernist?

“Master of Modernism and Creator of His Own Song Style” read the posters for Jazz trumpeter and singer Louis Armstrong when he appeared in Memphis, Tennessee in late 1931 at the end of a decade of development that saw him take the raw talent spawned in his hometown of New Orleans and spread it across all of America, bringing not just jazz, but modernism itself to both black and white audiences. In Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism, musicologist and Duke University professor Thomas Brothers traces the trajectory of Armstrong’s rise against the backdrop of the racial and cultural divisions of early 20th century America. Brothers takes readers deep inside the art of Armstrong and dismisses both the myth of Louis’ naïve, unlearned talent and the criticism of Louis’ sellout to white tastes with the ease of the master hitting a high note. In Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism, Louis Armstrong emerges not just as the founding father of jazz (and all American popular music that follows in its wake), but as the first true modernist of American art.

Master of Modernism picks up where Brothers’ earlier book, Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans leaves off. This second volume of what’s shaping up to be the definitive biography of Armstrong begins with Louis taking the train to Chicago in 1922 to join his mentor, “King” Oliver. With the “Great Migration” of African-Americans from the South to the Northern major cities of New York and Chicago came a demand for African-American entertainment that Oliver and others wanted to fulfill. As Brothers points out, some African-Americans, especially W.E.B. Du Bois’ condescending “talented tenth,” shunned their Southern roots as part of a drive “to better one’s position” and find acceptance in the white world, but many still recognized jazz as a link to a heritage that shouldn’t (and couldn’t) be left behind. Brothers sees Armstrong’s art reaching not just back to his New Orleans roots, but even farther back to the African legacy of the days of slavery. Brothers credits Armstrong with inventing not one, but two musical art forms, the first of which was a fixed and variable model in which the standard melody is followed by improvised variations on the theme. Armstrong “discovered” this fixed and variable model in the remnants of African percussion that survived and thrived in the South. “In other words,” Brothers writes, “the fixed and variable model, created in Africa and transmitted to the New World by enslaved people, accounts for the central qualities of jazz as Armstrong learned it, transformed it, and propagated it.” Ironically, slavery led to the quintessential form of expressive freedom.

Brothers excels in breaking down both the musical and cultural implications of the great recordings that document Armstrong’s development, all the while reminding us that the recordings are but poor relics of the stage performances where the artist-audience interaction really made jazz “hot.” Armstrong’s “Heebie Jeebies” brought scat singing to a new audience with its “assertive celebration of an unrefined, everyday African-American voice, the opposite of dicty snootiness,” Brothers suggests. The author praises “the chiseled perfection” of “Big Butter and Egg Man” that Gunther Schuller earlier compared to the works of Mozart and Schubert for its naturalness and simplicity. “West End Blues,” however, becomes the real game changer for Armstrong. “Though there were several mild precedents in the Hot Five series,” Brothers writes, “it is safe to say that no one had ever heard music quite like this before.” In that song’s fanfare, Brothers believes, “Armstrong aims… for the supple quality of throbbing life itself, a feeling of movement where nothing is fixed and everything is dissolving into something else.” “West End Blues” becomes Louis’ “Declaration of Independence” from all the trials and limitations life and art had previously set upon him.

Brothers stresses throughout the hard work and hard study Armstrong took on to become a great artist, all in the name of putting to rest once and for all the “garbage” idea of Armstrong’s music as a natural, naïve, and primitive phenomenon that magically came from thin air (just as Stanley Crouch’s Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker [which I reviewed here] did for Charlie Parker). With the urging of his classically trained, jazz pianist wife Lil Hardin Armstrong, Louis schooled himself in the classics and learned “white” notation to further expand his musical horizons and add to his already seemingly endless supply of ideas.

For some, Armstrong’s classical education went hand in hand with his “white turn” in late 1929 away from hot jazz to the more commercially successful “sweet” jazz of Guy Lombardo and others. For later generations of African-American jazz artists, Armstrong stood as a frustrating example to follow artistically early and a cautionary tale of selling out late. The second musical art form Brothers credits to Armstrong involves his ability to “radically paraphrase” popular tunes. Saxophonist Sonny Rollins later praised Armstrong for finding “the Rosetta Stone” to translate “the worst material” into art, but many continued to criticize Armstrong’s song choices. Brothers counters those criticisms by suggesting that Armstrong took such dreck and added “expressive ambiguity” that put him “in dialogue with the song itself,” thus refusing to buy into the premise of the lyrics and, perhaps, selling the audience something else they didn’t even know was in the deal.

Brothers clearly shows great affection for his subject, something I myself find unavoidable whenever thinking of Louis, so I can only imagine the effect of decades’ immersion in the master’s live and music. Armstrong’s life-long marijuana use, rather than an inconsistent strike against the man, becomes a more consistent piece of his life in Brothers’ hands. “Marijuana purged the stresses of his mind just as laxatives purged the germs that accumulated in his bowels,” Brothers colorfully and scatologically suggests. Armstrong near the end of his life expressed his appreciation on tape for “Mary Wana honey” and always pointed out in private the injustice of a system that hammered down on peaceful marijuana users while allowing violent racial hate crimes to slide by. Even Armstrong’s sad forays into movies in the 1930s—Rhapsody in Black and Blue (in which he performs in leopard skin leotard against a jungle backdrop) and a Betty Boop cartoon titled “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You” (in which Louis sings surrounded by nearly every cruel stereotype in the book)—transform through Brothers’ eyes from “Uncle Tom” sellouts to an inescapable ideological prison akin to those of Dmitri Shostakovich in Stalin’s Russia or Richard Strauss in Hitler’s Germany. “Americans like to think of the United States as immune to this kind of crushing intrusion of politics into the minds of artists,” Brothers concludes, “but here it is.”

By the end of Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism you’ll come away with a new understanding and appreciation not just of Louis Armstrong the musician, but also of Armstrong the African-American making his way in a white world still dismissive of everything he stood for. While American artists tried to catch up with their European counterparts such as Picasso who co-opted African art for modernism decades before, Louis Armstrong took his African-American inheritance and turned it into the one true indigenous American modern art form—jazz. During the 1931 Memphis show in which he was hailed as the “Master of Modernism,” Armstrong daringly dedicated the song “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead You Rascal You” to members of the Memphis police in the audience, many of whom were Ku Klux Klan members. Singing with charm and humor that masked the intentions of the song’s lyrics, Armstrong found himself not in jail or at the end of a noose but on the receiving end of appreciative thanks from the policemen. Being Armstrong the high note king could often become Armstrong the high-wire act without a net—full of danger, always on the edge, but lots of fun, too. Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism puts the danger back into the life of Louis Armstrong as much as the fun of being the best of a new wave of art.

[Many thanks to W.W. Norton for providing me with a review copy of Louis Armstrong, Master of Modernism by Thomas Brothers.]