Understanding Up and Down Cycles of News Attention to Climate Change

–Guest post by Sarah Merritt, American University doctoral student.

News attention to climate change appears to follow a narrative cycle, where according to communication researchers Katherine McComas and James Shanahan (1999), rather than reflecting the objective conditions of the issue, coverage will follow closely the issue’s dramatic qualities including claims related to risks and costs as well as the surrounding political conflict.

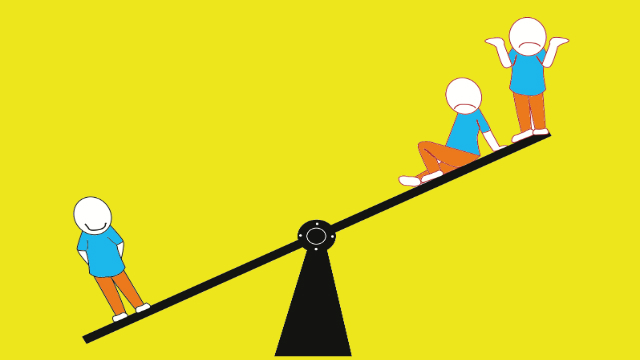

This process leads to up and down cycles of news attention or ‘spasmodic reoccurrences” in coverage. As Max Boykoff has tracked, U.S. news attention spiked in the build up to the November 2009 Copenhagen meetings but then moved to a new period of depressed coverage in the months and years since.

According to McComas and Shanahan, over the years, media coverage of climate change has followed a narrative path that cycles through four major stages that relate to the amount of attention the issue receives. First, during a period of rising media attention, there is a dramatized implied danger. Examples include the period of the late 1980s as the general threat of climate change was discovered or starting in 2006 when the connection to extreme weather and natural disasters was highlighted by Al Gore and some scientists.

Second, attention to these dramatic threats then leads to a debate over scientific certainty as was the case through the 1990s on manmade causes generally or since 2006 on the connection to extreme weather, the overall severity of the climate change threat, or the timeline until society reaches human induced “dangerous interference” with the Earth’s climate. Third, at the peak of news attention, momentum and support to address the threat begins to subside, as there is a strong focus on the economic costs associated with action. An example is the period 2009-2011 as heavy debate focused on the costs associated with cap and trade legislation, a debate amplified by the economic recession. Fourth, coverage moves to a denouement stage where attention to the problem remains low as appears to be the case today.

So what are the conditions that are likely to start this cycle over again leading to a rise in news attention to climate change? It is possible that the number of extreme weather-related events across the U.S. and internationally may be the new threat that builds attention. Yet as Matthew Nisbet and Michael Huge describe in a study examining cycles of attention to science debates generally, these events are likely to be covered by specialist science journalists, for the most part. With a decreased number of such specialists at news organizations today and a decrease in overall space devoted to public affairs generally, these industry trends are likely to further constrain attention.

It is likely that only when a new major political decision is on the horizon such as national legislation – following the 2012 election – will news attention to climate change again spike. Part of this rise in coverage will be the transfer in attention across news beats as science journalists are joined in their coverage by political reporters and opinion writers, a shift catalyzed by the media lobbying efforts of advocacy groups and political leaders. Again, in this build up to the decision, according to McComas and Shanahan’s model, there will likely be a heavy focus on the associated costs of action.

Important to note is that McComas and Shanahan’s study and Boykoff’s tracking of coverage only includes print coverage. A number of outlets such as the New York Times and Washington Post continue to produce considerable coverage of the issue via blogs such as Dot Earth and Post-Carbon. Future studies of the narrative cycle on climate change and patterns of attention needs to take into account the web-based content provided by news organizations and weight this content against the total agenda-setting impact of the news organization.

–Guest post by Sarah Merritt, a doctoral student at American University’s School of Communication. Read other posts by AU doctoral students and find out more about the doctoral program in Communication at American University.

References:

McComas, K., & Shanahan, J. (1999). Telling stories about global climate change. Communication Research, 26(1), 30.

Nisbet, M., & Huge, M. (2007). Where do science debates come from? Understanding attention cycles and framing. In Brossard, D., Nesbitt, C., & Shanahan, J. (Eds), The media, the public, and agricultural biotechnology, 193–230. [PDF]

See Also:

Nisbet, M.C. (2011, April). The Death of a Norm: Evaluating False Balance in News Coverage. Chapter 3 in Climate Shift: Clear Vision for the Next Decade of Public Debate. Washington, DC: American University, School of Communication.