Three Poets, One Epitaph: Hardy, Yeats, Frost (Pt. 1)

In a mid-career essay about his elder contemporary Robert Frost, the poet W. H. Auden observes that “[Thomas] Hardy, [W. B.] Yeats and Frost have all written epitaphs for themselves.” He quotes all three epitaphs, which in their final versions read as follows:

Hardy

I never cared for Life: Life cared for me,

And hence I owed it some fidelity…

Yeats

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

Frost

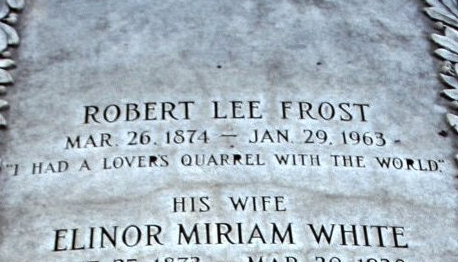

I would have written of me on my stone

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world.

Auden adds a passage of wry commentary worth repeating in full:

Of the three, Frost, surely, comes off best. Hardy seems to be stating the Pessimist’s Case rather than his real feelings. I never cared…Never? Now, Mr. Hardy, really! Yeats’ horseman is a stage prop; the passer-by is much more likely to be a motorist. But Frost convinces me that he is telling neither more nor less than the truth about himself. And, when it comes to wisdom, is not having a lover’s quarrel with life more worthy of Prospero than not caring or looking coldly?

I agree and would go further: Frost not only sums himself up accurately, he sums up the other two as well. The phrase “lover’s quarrel” is surprisingly apt in describing the work and worldview of all three men. All three had embattled and creatively fertile relationships with the women in their lives—including, in Hardy’s case, his wife Emma; in Frost’s, his wife Elinor; and in Yeats’s, his elusive lover Maud Gonne. The poetry of all three dramatizes an ongoing negotiation (or feud) with either an actual lover or the world figured as such. Just as a quarreling lover can take a certain grim pleasure in scoring points against his opponent, Hardy, Yeats, and Frost are all masters of glorious negativity. These poets find themselves in their alienation from the Other;irascible as they are, they find considerable romance, too. And while the world may always win in the end, they eke out an impressive number of moral victories in their poems, including the victory of emotional honesty. In their separate ways they are as worthy of Frost’s epitaph as it is of them.

* * *

Of the trio, Thomas Hardy is by turns the dourest and the most sentimental. His love poems range from the gauzy and heartfelt “Beeny Cliff” (an elegy for Emma) to the ironically titled “Neutral Tones,” which contains some of the iciest lines in English poetry:

The smile on your mouth was the deadest thing

Alive enough to have strength to die;

And a grin of bitterness swept thereby

Like an ominous bird a-wing…

In a precedent that will recur throughout the work of all three poets, “Neutral Tones” projects the qualities of the lover and the difficult love onto “the world”—in this case, nature. Not only is the person addressed bitterly smiling, but the leaves on the surrounding sod are “gray,” the sod itself “starving,” the sun “white, as though chidden of God,” and so on. In “Beeny Cliff,” by contrast, the woman seen from afar redeems even the bleakest features of the landscape: the falling rain is “irised,” and the “stain” on the sea turns to “purples” when the sun “burst[s] out again.” As a recollection of the wife from whom he later became estranged, this seems remarkably generous, whereas for all its impact, “Neutral Tones” forces us to ask whether its harshness is excessive. Even in the depths of our most traumatic love affair, how many of us would call the winter sun “God-curst”?

In “A Broken Appointment,” which finds Hardy’s speaker quarreling with a woman over an unrequited love, it’s Time in particular that allies with the Other. “You did not come,” the poem begins, “And marching Time drew on, and wore me numb…” Set in grammatical parallel, the inaction of “you” and the action of “Time” conspire to disappoint. At the end of the same stanza the speaker recalls his grief “as the hope-hour stroked its sum,” and in the second stanza he refers to himself, wistfully, as “a time-torn man.” Time and the woman are against him, no less than Nature and the woman in “Neutral Tones.” The luxuriant self-pity of these lines, their dignified indignation at the woman’s lack of “pure lovingkindness,” anticipates the mature work of Yeats.

Even when the poem’s subject isn’t love, Hardy’s genius flourishes in quarrel with the world. He is quite capable of universalizing his personal grudges, but also of moving beyond self-pity into pity for all mankind.

Such is the tone he strikes in “Channel Firing,” possibly his best poem and the one that best embodies the delicate balance implied by Frost’s phrase, “lover’s quarrel.” Written on the eve of World War I, it maintains an odd gentleness of tone despite its deep cynicism; the poet is shaking his head but not shaking his fist. The perspectives it juggles—that of God, the dead, and the animals—are detached from the common lot of humanity; through them Hardy is able to communicate the futility both of war and of trying to end war. You could say he is quarreling with the ongoing human quarrel, yet his reproaches have an almost affectionate quality. The voice of God in this poem (who chuckles and uses the homely cliché “mad as hatters” to describe human nations) sounds not unlike that of the dead local parson, who wishes that “instead of preaching forty year…I had stuck to pipes and beer.” One by one these judgments build, through brisk iambic pentameter quatrains (the poem is an ironic march), to a grand evocation of the universal din of battle:

Again the guns disturbed the hour,

Roaring their readiness to avenge,

As far inland as Stourton Tower,

And Camelot, and starlit Stonehenge.

If you have to point to a moment not just of brilliance but of sublimity in Hardy’s poetry, this would be it. The music of those two closing spondees is gorgeous, and his grouping of the imaginary Camelot with the two authentic landmarks—as though you could visit all three on the same tour—is an inspired touch. It is quintessential Hardy to allow himself this slight romantic indulgence precisely at the moment when he’s despairing over mankind’s prospects for redemption. Just for an instant, he gets transported by cynicism, the way Shelley sometimes gets carried away by idealism. And of course, there is the irony that Camelot itself is an ideal, one no less tainted by the destructive myth of military glory than any number of real-world monuments.

Over the course of nearly a thousand poems Hardy’s quarrel with love, lovers, and the world encompasses just about every possible tone except neutral. Sometimes he seems to be “stating the Pessimist’s Case,” as Auden has it, and can sound peevish or defensive. (In the epitaph “I never cared for life, life cared for me,” I hear: “I broke up with life, not the other way around.”) At other moments he verges on sentimentality (as in “Beeny Cliff,” which seems to me an idealized portrait) or lugubriousness (the end of “Neutral Tones,” although nothing can detract from the brilliant nastiness of the stanza quoted earlier). What he rarely if ever shows is perfect Keatsian negative capability; it’s impossible to imagine him, for example, participating in this kind of lover’s quarrel:

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

That is, he rarely brings such markedly clashing attitudes into close conjunction. His poems tend to know where they stand, and argue with each other more than with themselves: that is the source of their limitations but also of their pugnacious greatness.

Part 2 of this essay, on W. B. Yeats, will appear tomorrow.