Study: To Prevent Abuse of Power, Focus on Procedure, Not Results

If there’s one thing that unites the good guys in movies and TV shows, it’s a hatred of “procedure”—those legal niceties that get the bad guys out of jail and prevent the hero from finding the bomb in time. Who cares about regulations? Results are what matters. And it’s not, of course, a sentiment confined to screenplays: Any news about terrorism or potential terrorism is followed by the cawing of pols and pundits trying to sound like Dirty Harry. Keep Guantanamo open! Don’t stop water-boarding! Don’t read Dzhokhar Tsarnaev his rights! Be glad the NSA is secretly monitoring everyone’s phone calls! This is war—no time to be worrying about crossing t’s and dotting i’s! It’s an easy message to sell in a fearful time (those movies primed us well for it). But according to this study in a recent issue of the Journal of Applied Psychology, it encourages abuses of power.

In a trio of experiments, the authors, Marko Pitesa of Grenoble’s Ecole de Management and Stefan Thau of the London Business School, found that people who expected to be judged on the results of their decisions were far more likely to abuse the trust placed in them than were people who expected to be judged on the procedures they used to decide.

In one experiment, for example, they organized 61 male and 43 female undergraduates (presumably from Grenoble) into six-person groups, in which some were informed that they would be “in charge” and others told they would be expected to “work with others.” While they waited for their teammates to arrive, each student was given a task, supposedly to fill the time. The task (which was in fact the real experiment) was to manage the money their group would receive for being a part of the experiment (five euros per person). Whatever they “invested,” they were told, had a 50 percent chance of doubling and a 50 percent chance of disappearing. So each person’s decision would determine how much fellow team members would receive. Moreover, the investor would get a 20 percent “investor’s fee” on any profit from the decision. Best part: Each person, though deciding for others, was immune to risk—his or her own five euros wouldn’t be in play. The idea was to duplicate the situation of a financial agent handling other people’s money but not risking his own.

The rest of the experimental design cleverly combined a psychological question and an institutional one. Remember that some of the volunteers had been told they would be in charge, while others learned they were to be worker bees. This created two types of “investor”—those who were told they had power in the lab and those who were told they did not. Pitesa and Thau expected that the people who felt more powerful would be more reckless with other people’s money.

However, the experimenters also wanted to test how this psychology of power interacts with different kinds of institutional safeguards. So before the task, they told some volunteers that they would be expected to explain to teammates how they had made their decision. Others were told they would have to focus on the good or bad results.

As you might expect, feelings of power made people more willing to take risks that might hurt others: the “bosses” were willing to gamble more of their teammates’ money than were the non-bosses. But the difference between bosses and peons was not that great. Much more impressive was the effect of the two different forms of accountability. Those who expected to describe their decision-making process risked a great deal less money than those who expected to be judged on outcome. (Specifically, the “bosses” who focussed on possible results invested an average of €14.62 of other people’s money, while those who instead focussed on procedure invested a mere €5.08 on average. )

The authors also got similar results in an online experiment with 63 lawyers (those who described themselves as powerful were more willing to recommend a risky investment than were those who felt less so, and those who had to account for their decision-making process were far less likely to gamble with others’ fates than were those who knew they would be accountable for results).

The theoretical argument here is an attempt to move the theory of abuse of power away from a rationalist model, in which all people are expected to behave in the same way. (The conventional wisdom in the field, according to Pitesa and Thau, is that, like rational robots, we all try to get away with as much as we can, and that we are kept in check by rules that make it too costly to cheat others. They wanted to explore why some people cheat more than others in the same situation, and why some safeguards work better than others, even though the costs they impose are the same.)

You needn’t be into those theoretical questions, though, to find the study rather haunting, given this week’s news. Its first take-away here is that, as us non-bosses have suspected for millennia, power inclines people to do what they want, with less-than-average concern about how their decisions will affect others. And the second take-away is that if you want to inhibit this recklessness, don’t focus on results. Focus on procedure. Or, to extrapolate (I think reasonably): If we judge powerful people by their results (like, oh, number of terror attacks prevented) they will behave more self-servingly more often than if you judge them by their procedures (as in, oh, is this actually constitutional?).

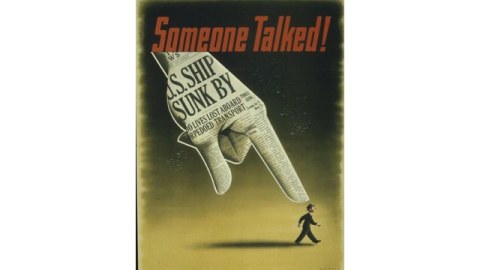

Illustration: 1940s-era anti-blabbing poster, from the Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services. Via Wikimedia

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby

Pitesa, M., & Thau, S. (2013). Masters of the universe: How power and accountability influence self-serving decisions under moral hazard. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98 (3), 550-558 DOI: 10.1037/a0031697