Should the Mona Lisa’s Smile Be Saved?

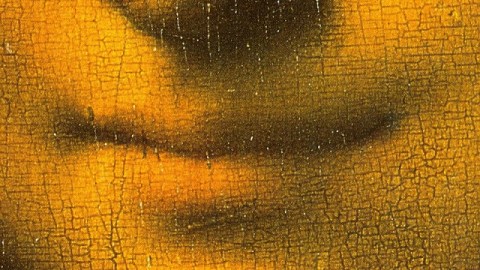

If you saw someone dying before your eyes, wouldn’t you do everything possible to save them? Is there ever a case when saving someone (or something) is the wrong choice? In a recent article on Art Watch UK titled “What Price a Smile? The Louvre Leonardo Mouths that are Now at Risk,” Michael Daley raises the issues surrounding what he calls “a wid[ening] international art conservation faultline” between conservative conservators who refuse to risk doing harm to great works of the past through cleanings and restorations and more aggressive conservators who feel that the benefits of modern conservation outweigh the (to them, minimal) risks. What raises Daley’s hackles the most is the shift from conservative conservation to almost radical change at the Louvre, the granddaddy of all art museums and past champion of the “do no harm” school. Not only has the philosophy changed at the Louvre, but, as Daley notes, some paintings by Leonardo da Vinci have already been changed with no debate on the issue. The Mona Lisa’s smile (cracking and faded, but still there, above) hasn’t undergone cosmetic surgery yet, but it seems the next step. Knowing the risks, should the Mona Lisa’s smile be saved?

How is it possible that the status of paintings hundreds of years old is suddenly changing before our eyes? How can works deemed too fragile for alteration can be touched now? Daley points to the resignations from the Louvre’s own international advisory committee of Sègoléne Bergeon Langle, former director of conservation at the Louvre and France’s national museums, and Jean-Pierre Cuzin, former director of paintings at the Louvre. Those two key figures quit essentially over what they saw as the overcleaning of the Louvre’s Virgin and Child with St. Anne. “Restorations never take place in antiseptic clinical spaces,” Daley explains. “They always reflect philosophies, interests and professional inclinations or disinclinations towards radical interventions. Conflicts in this arena are far from trivial and it is desirable that they should not take place in the dark.” Apparently factions within the Louvre decided to “fix” the da Vinci without fully consulting with the factions that disagreed with them. (Daley’s article illustrates the changes.) That secrecy seems to stretch to the public, as Daley notes that “[n]ews of the Louvre resignations comes just seven months after the shocking disclosure of its cosmetic facial exercises and at the point where the cleaning of the ‘St. Anne’ is completed and the perilous stage of retouching begins.” The schism between those in-house groups at the Louvre (and the art world in general) may be as irreversible as the actions taken on Leonardo’s depictions of the Virgin Mary and St. Anne.

da Vinci’s art brings this simmering debate to a boil. In addition to Leonardo’s high international profile, the subtlety of his techniques, especially the sfumato or “smoky” effect of multiple layers of thinly applied paint to create the unique effects of the Mona’s smile and other works, provides a challenge that most conservators previously would not accept. Has conservation really come that far to dare to go where no re-toucher has touched before? “Must every restored masterpiece immediately trigger another?” Daley asks. “Will curators and their restorers never allow decent intervals for the fumes to evaporate and for their handiwork to be evaluated with due attention and consideration after the inevitable PR media barrages that nowadays accompany all major restorations?” You can almost hear him hyperventilate over the changes to these masterpieces multiplying as the goalposts on what is acceptable conservation practice shift to more radical measures with little time for consideration. (Daley’s article also illustrates severe changes made at other major art institutions.) Everyone wants to see a “new” da Vinci, right? A cleaned-up Mona might finally reveal the secret of her smile?

But what could be the cost of looking for that secret? Some of the paint Leonardo applied five centuries ago to the most famous portrait in the world has already disappeared. Mona’s eyebrows, which we know of today from copies made hundreds of years ago, disappeared into the atmosphere at some point. We just don’t know what else has been lost, or what we might lose in the future. That could be an argument for conservation now—save what we can. Or it could be an argument for doing as little as possible—accepting our ignorance or technical incapacity to do more good than ill with grace and humility. Today’s museum conservator knows full well the long and tragic past of museum conservation that challenged the boundaries and paid a dear cost for both their generation and all those that followed.

Daley’s right that both sides need to participate in the debate about how far and how fast to go in the conservation of masterpieces of Western art. I’m sure he would also add that there’s another unheard voice in this debate—that of the public itself. I confess I don’t know how we’d put this up to a vote (Art patrons? French citizens? An international audience?), but I’d like to think that we all own a bit of the Mona Lisa as part of our shared heritage. I’ve made the pilgrimage to the Louvre and braved the crowds for a glimpse of “La Joconde,” and hope for the same for my children and their children. Even if they never make it to Paris, just the idea that such a masterpiece defied the ages in some way—bearing the ravages of time like a badge of honor—is something worth preserving. Risking the ruin of Mona Lisa’s smile (or the details of any artwork from the past) in that context seems the height of hubris and selfishness.

[Image:Leonardo da Vinci. Mona Lisa (detail), 1503-1519.]