Paul McCartney’s Seventies Struggle to Escape the Beatles

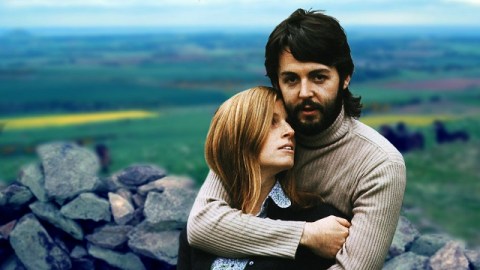

During the 1960s, four of the most famous people on Earth were collectively known as The Beatles. Most people struggle to deal with the post-fame life, but how do you live as an ex-Beatle? In Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 1970s, Tom Doyle asks that very question of the life of the “cute Beatle,” Paul McCartney. For McCartney, the 1970s “was an edgy, liberating, sometimes frightening period of his life that has largely been forgotten,” Doyle writes in no small part because beneath the myth of the “Bambi-eyed soft-rock balladeer, [Paul] was actually a far more counterculturally leaning individual (albeit one overshadowed by the light-sucking John Lennon) than he was ever given credit for.” Thanks to years of exclusive interviews with McCartney and people close to him during this era, Doyle paints a far more interesting portrait of the writer of “Silly Love Songs” as an eccentric, experimental, and even inspirational artist whose partnership with wife Linda McCartney (shown above together with Paul) showed him how to escape the shadow of the Beatles and find a new life and career.

Few people have faced as many interviews in their lifetime as McCartney, usually centered around the same questions resulting in the same, tired answers. Doyle’s approach in asking questions about Paul’s post-Beatles struggle reveal a different side of the musician. “Most people, from the Beatles’ films and his countless TV interviews, have some idea of how Paul McCartney talks,” Doyle writes. “Face-to-face, however, his tone is more earthy, more Liverpudlian, his speech peppered with lovingly delivered swear words.” Doyle scratches through the veneer of the knighted millionaire icon to reveal the working-class man still lurking beneath and still guiding so many of his life decisions.

Doyle begins at the Beatles’ end. “This was an identity crisis in extremis,” Doyle explains. “Who exactly was he if he wasn’t Beatle Paul McCartney?” The stress debilitated Paul, rendering him unable to even rise from bed. His wife Linda watched in horror as the man she just recently married crumbled before her eyes, which she described as “frightening beyond belief.” Linda rescues Paul by retreating to his previously unused farm in High Park, Scotland. There, the couple adopted what Doyle calls “rural personas” as they fixed up the property for themselves and their growing family and learned the basics of the farming life far from the maddening crowd contending over the Beatles’ tangled finances and the public clamor for the group to reunite and make more music. As Doyle points out, the song “Man We Was Lonely” captures the conflicted nature of this necessary withdrawal McCartney now calls his “therapy through hell,” but another song—“Maybe I’m Amazed”—celebrates how the strength of their marriage pulled him through. As part of this therapy, McCartney cobbled together a recording studio on his farm to begin again, working with what he called “pure sound” free of all Beatles’ baggage. Doyle manages to tie together the music, the man, and the moment in a way that most people fail to do because of McCartney perceived lightness. To see dark biographical matter in these melodies seems wrong, but Doyle rightly proves that it’s clearly there.

Eventually the solo life left McCartney wanting more, specifically a group for “camaraderie” as well as “musical turn-on.” Thus, Wings was born. (The name came to Paul as he waited for news of daughter Stella’s birth by emergency C-section and he imagined the “simple, calming beauty” of an angel’s wings.) Doyle works his way through all the ups and downs and strange moments of Wings: the continual turnover in personnel save for Paul and Linda, herself a reluctant and controversial member; the unconventional college tour at Wings beginning; a brief foray into politics with the song “Give Ireland Back to the Irish”; an even odder foray into children’s music (complete with embarrassing music video) in “Mary Had a Little Lamb”; the difficulties of recording in Lagos, Nigeria, for the album that eventually became Band on the Run,Wings’ most successful album; the success of the “Wings Over America” tour that inspired a TIME Magazine cover “McCartney Comes Back”; and even the unlikely success of the bagpipe-featuring “Mull of Kintyre,” a song Doyle calls “the monumental hit record that [Paul] never anticipated or, deep in his rocker heart, necessarily wanted.” Throughout this period, Doyle never fails to recreate the experimental, seat of your pants, sometimes falling on your face feeling of McCartney’s artistry.

Doyle also honestly portrays the “man out of time” side of McCartney in the 1970s. Still filled with that Sixties spirit, McCartney couldn’t keep up at times with the latest musical fashions or social shifts, most seriously in attitudes towards drugs such as marijuana—the McCartneys’ drug of choice. Arrests for possession while on tour painted a bull’s eye on their backs that never disappeared, yet the pair continued their advocacy of pot over what they saw as more dangerous drugs such as alcohol. Doyle provides valuable context of what happened to McCartney contemporaries, such as John Lennon’s “lost weekend” and marital problems (which the McCartneys helped resolve in ways rarely acknowledged) and the tragic, but somehow inevitable deaths of Keith Moon, John Bonham, and others. 1980 marked not only the end of the 1970s, but also the end of the 1960s for McCartney and his generation. On January 16th, Japanese officials arrested McCartney for possession of marijuana and imprisoned him briefly with the possibility of facing up to 7 years in prison. “I was an idiot,” McCartney says now of that dark time. “It was clear that Paul’s freewheeling years were over,” Doyle concludes with no little understatement. On October 9th of 1980, Paul spoke on the phone to John Lennon for the last time on Lennon’s 40th birthday. Two months later, a troubled fan killed Lennon in New York City. McCartney had finally come to peace with his Beatles past only to see it disappear in one mad act. Paul initially lived with increased security, but soon realized that “[h]aving never allowed his fame to hamper or hinder him in the past, having taken a determinedly ordinary approach to his everyday activities,… living behind a wall of security was not for him.” Nevertheless, for varying reasons, McCartney didn’t tour again for a decade. “To just come out of that period was a good thing,” McCartney says now of the 1970s. “I survived.”

During their most divided time, Lennon venomously cracked that McCartney was “all form and no substance.” Such criticisms still cling to the reputation of Paul McCartney, even when he’s become a living symbol of England itself in moments such as his performance at the 2012 London Olympics. Knights of the realm aren’t usually radicals, too, but Tom Doyle’s Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 1970s makes a compelling case that Sir Paul McCartney is both, and much more. “While elsewhere Lennon was screaming his pain,” Doyle contrasts the two main Beatles, “it was typical of McCartney to mask his with melody. Only if you listened closely would you really be able to detect the songwriter’s anguish.” Man on the Run asks us to listen closely to the “Silly Love Songs” of McCartney in the 1970s and hear, maybe for the first time, the anguish of a man crawling out from beneath the crushing fame of the Beatles and eventually standing on his own—often eccentrically, sometimes infuriatingly, but eventually enduringly.

[Many thanks to Random House for providing me with a review copy of Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 1970sby Tom Doyle.]