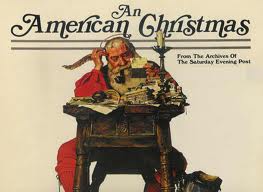

Let’s Have an American Christmas!

As some more traditionalist and religious conservatives have noted with disgust, that’s the advice of Ayn Rand:

The best aspect of Christmas is the aspect usually decried by the mystics: the fact that Christmas has been commercialized. The gift-buying . . . stimulates an enormous outpouring of ingenuity in the creation of products devoted to a single purpose: to give men pleasure. And the street decorations put up by department stores and other institutions—the Christmas trees, the winking lights, the glittering colors—provide the city with a spectacular display, which only ‘commercial greed’ could afford to give us. One would have to be terribly depressed to resist the wonderful gaiety of that spectacle.

In a country like ours, Rand proclaimed, holidays will stop having predominately religious or other-worldly meanings. Ours is a capitalist Christmas! It’s commercial ingenuity aimed at the rational (and, of course, selfish) goal of giving people pleasure. Who could remain depressed watching “the wonderful gaiety” of “the spectacular display” of commercial greed?

Well, studies show that Christmas with lots of stuff and without family and God—without being in one sense or more “home for the holidays”—actually gets people down almost more than anything. It’s routinely American, after all, to write a story making that obvious point.

We might say, in a beginning of a criticism of Rand’s crude reductionism, that she really doesn’t explain the pleasure of gift-giving. Or even that of gift-receiving.

Someone might say, in support of the Rand thesis, that Christmas didn’t even become a national holiday until 1870. And it was around that time that the commercialization of Christmas was pushed insistently by the original huge department stores—beginning with Philadelphia’s Wanamaker’s. We see in that wonderfully American and instantly traditional movie A Christmas Story (in which religion plays no role at all) the view that it’s the glitter of the department store—and its Santa—that are at the real center of our Christmas longings.

We have to admit that the spectacular display that is the American city at Christmas has been in decline—at least in terms of class—with the fading away of the downtown department store.

We remember, of course, that the original Americans—the Puritans—opposed Christmas for Christian reasons. It’s nothing but a pagan holiday that justifies all sorts of decadent excesses in the name of birth of the son of God. Anyone who knows a lot about the drunken and often destructive revelry of “the lords of misrule” in late-medieval England know the Puritans had a point. Unfortunately, every time those Puritans had a point, they tended to push it beyond all reason.

Anyone familiar with the moving celebratory words and music of the English carols knows that Christmas was also quite a properly joyous festival in honor of that redemptive birth: “O Come All Ye Faithful,” for example. (Even the Bob Dylan version of “Adeste Fidelis” manages to be joyous.)

Our objections to the excessive commodification of Christmas remains basically Puritanical. Our secularized Puritans sometimes display a hostility to the very idea of the religious holiday as offensive to our egalitarian identity. But often the objection is softer and on behalf of a more Christian Christmas. The evangelicals in my semi-rural county sometimes display signs saying “Christmas is a birthday” in their yards. And the objection to turning “Merry Christmas” into “Happy Holidays” is sometimes to the pointless hyper-commercialization Rand celebrates and Walmart promotes.

Our Puritans were against Christmas because it was un-Christian. And our founders dissed it because it was un-republican and un-American. It was a decaying English tradition unfit for our enlightened way of life, our new order of the ages.

The Christmas revival in the South was quicker and very antebellum. The aristocratic southerners quickly became attuned to the gentle relational pleasure of traditional celebrations. And they lost Mr. Jefferson’s hostility to what the Bible actually says about God becoming man by being born of a virgin.

We find another distinctively southern American form of Christmas in the “Christmas spiritual.” Most of these haunting tunes adorned with elegantly simple and profoundly Biblical words were written by slaves and collected after the war. They were preserved and popularized through African-American churches and groups such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Here is a good list of the top ten Christmas spirituals. It has two flaws that I’m able to notice. Where’s “Mary Had a Baby”? And “I Wonder as a Wander” is a white Appalachian Christmas song, which is also a distinctively American but somewhat different genre.

These spirituals typically had double meanings. They indirectly refer to the coming redemptive act of being liberated from chattel slavery. But they also, quite authentically, refer to the redemption described in the Bible, the redemption from sin and from our homelessness in this world. Our African-American poets, at their best, showed us that neither form of “the theology of liberation” should stand alone.

So we might begin with them in developing our American criticism of Rand.

Here is a verse of the Christmas spiritual “Go Tell It on the Mountain”:

When I was a seeker

I sought both night and day

I asked the Lord to help me

And he showed me the way

Who can deny that’s somehow both the liberation described in Exodus and that described the gospels? It’s the truth—the truth about who we are—that shall set us free.