Is This the “Missing Link” of Shakespeare Studies?

Critics usually pose the greatest literary mystery of them all—the authorship question surrounding the works of William Shakespeare—as a “whodunit,” but it’s more of a “howdunit.” How could the small-town son of a glover develop into the world-renowned author of works not just of intricate verbal playfulness and deep psychological insight, but also of erudition seemingly beyond someone who never went to college? Since the 19th century, the “how” has been so improbable that critics have searched for a “who” who better fits the bill of the title of the Bard. Two antiquarian booksellers, George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, believe that they’ve found the “missing link” of Shakespeare studies in the form of an obscure, unusual, 1580 reference book called John Baret’s Alvearie (an old word for “beehive”) that they argue was owned and extensively annotated and used by Shakespeare himself. According to their theory in Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light, the Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon took the erudition he found in the pages of Baret’s work and imaginatively transformed it into his art. It’s a theory that sounds stranger than fiction, but if they’re right, they’ve made the greatest find in Shakespeare studies of the 21st century.

The idea that Shakespeare borrowed heavily from his sources is well known. Shakespeare relied on Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland for many details found in his history plays. Many of the comedies and tragedies also originated from ancient and not-so-ancient sources. Even Hamlet probably sprung from a now-lost Ur-Hamlet possibly written by Shakespeare’s contemporary Thomas Kyd. Shakespeare’s time simply didn’t emphasize originality as ours does. Although Shakespeare took inspiration (or more) from his sources, he always found a way to stamp his own imaginative mark on them.

It’s that transformative imagination that Koppelman and Wechsler see at work in their copy of Baret’s Alvearie, which they purchased in 2008 for $4,050 on eBay. When the book arrived at their shop a week later, they noticed that the book had been well cared for and extensively used, as shown by the numerous annotations throughout. Although neither of the booksellers are Shakespeare scholars, they did know that Shakespeare used source books, but had never heard of Baret’s Alvearie listed among them. After doing some research, they found that many scholars believed that the secret to Shakespeare’s language might reside in one or more of the many dictionaries available during the period. However, one scholar they found—T.W. Baldwin—tucked away a tantalizing suggestion that Shakespeare may have used Baret’s Alvearie in a massive, two-volume study of Shakespeare from 1944. “The idea that Shakespeare may have often turned to any copy of Baret—there was magic for us in the simple thought of that alone,” Koppelman and Wechsler write. The idea that they possessed the very copy Shakespeare may have owned seemed too impossible to be true, but too irresistible to not pursue.

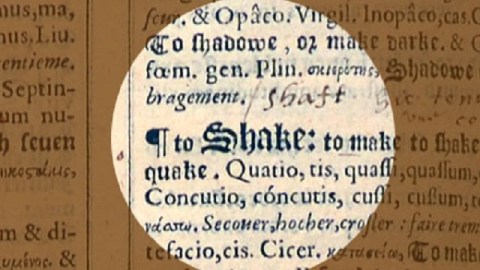

Koppelman and Wechsler went on to break down the annotations in their copy into different categories: “mute” annotations such as underscores, slash marks, or small circles versus the “spoken” annotations consisting of single words or phrases that appear over 1,000 times in the copy. The next step was connecting those marks to Shakespeare. On their website they give just one example of these annotations “in action.” Baret’s Alvearie gets its beehive-like buzz from the way that the entries involve different languages all at once—cross-referencing between English, Latin, French, and Greek incessantly. As the authors point out, Baret actually coined the term “hard words” to mean words too obscure for everyday use. An author hoping to sound smarter than his level of education would understandably turn to something like the Alvearie. “For someone obsessed with innovation in regard to words” such as Shakespeare, Koppelman and Wechsler write, “the Alvearie must have represented a dream tool, with its emphasis on variable options and its pooling network of sources, proverbial phrases, and multilingual comparisons. The obsessive annotator of our copy may indeed embody the sort of language-obsessed person one would expect to find in the margins.” But is the person we “find in the margins” of their book Shakespeare?

More than half of their publication Shakespeare’s Beehive makes the textual case for the connections, linking words or clusters of words to passages from the plays and poems in a meticulous display of scholarship for a pair of self-professed non-scholars. (Casual Shakespeare readers might find this evidence pedantic, confusing, tedious, or all the above. Welcome to academia!) They’ve made digital copies of the book available online for scholars to judge for themselves, which should silence any accusations that Shakespeare’s Beehive is a sensationalist attempt to cash in on Shakespeare’s 450th birthday celebration this year. Perhaps the simplest and most convincing annotations are those that connect to Shakespeare the man, or, more specifically, Shakespeare the name, such as the “shaft” added to the word “Shake” (shown above), with “shaft” and “spear” being synonymous. My favorite annotations were imitations of the font beside entries for “W” and “S,” which seem perfectly natural for a small-town author looking for a suitable signature to match his growing reputation. Shakespeare felt the sting of his humble beginnings enough to pay for the status symbol of a coat of arms emblazoned with the epigram “Not without merit” (which friend Ben Jonson satirized in a play as “Not without mustard”). Nothing seems as natural, as human, as Shakespearean as that signature practice, at least to me.

Not all of Shakespeare’s coinages—his words and phrases that are now part of the DNA of the English language itself—were winners. “Exchange me for a goat, / When I shall turn the business of my soul / To such exsufflicate and blown surmises, / Matching thy inference,” Othello says to Iago in scene 3 of Act 3 of Othello to warn the schemer that he’s not easily made jealous. It’s the first and last recorded usage of “exsufflicate” (perhaps taken from the Latin “exsufflare,” meaning “to blow away”). I doubt many in the Elizabethan audience went home looking to use “exsufflicate” in a sentence, perhaps contributing to its loss to the winds of time, but people have always wanted to find a way to sound smarter faster for many reasons. A recent article bemoaned the students’ misguided use of “Brainy Quote”-like sites for quotes in hopes of smarter-sounding papers and higher grades. Was Baret’s Alvearie simply Shakespeare’s “Brainy Quote”? Yes, and no. Yes, he was looking for an instant education. But, no, his use was filled with an insatiable hunger for language rather than a desire for an easy “A.” Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light by George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler may not have found Shakespeare’s copy (even they acknowledge problems of provenance, handwriting, etc.), but they definitely have found a way for us to appreciate Shakespeare the author not as a god-like creator, but rather as a mortal-as-us, hard-working student of language, earning each turn of phrase and new coinage in a college of his own making. This “missing link” may not truly solve the authorship question mystery, but it does add the clue that the writer was more human, more hardworking, and more humble than we suspected.

[Image: Highlighted annotation S291 in which the word “shaft” is written in near the entry for “Shake” from Baret’s Alvearie in Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light.]

[Many thanks to the authors and Axletree Books for providing me with a review copy of Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light by George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler.]