When David Bowie played Andy Warhol in the 1996 film Basquiat, he wore Warhol’s actual wig and glasses. Bowie met Warhol in his travels through the art world and even played the song he wrote about him to Warhol, which Andy, of course, didn’t like. In an interview leading up to the exhibitionDavid Bowie is (at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, Canada, through November 27, 2013), artist Jeremy Deller compares Warhol’s influence on the 1960s to Bowie influence on the 1970s. “They both ruled the decade,” Deller claims. “They defined it and they changed it.” However, the artist that Bowie mirrors the most may be another of his favorites, Pablo Picasso. Like Picasso, the single constant in Bowie’s career has been being on the cutting edge of change. Over the years, Bowie’s been Ziggy Stardust, Tao Jones, Halloween Jack, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, and John Merrick, the “Elephant Man.” But Bowie’s always been Bowie through all those incarnations. David Bowie is shows you how he’s been all those things and more, but also what he “is” today—an influential force beyond any single art form, the Picasso of our time.

The Art Gallery of Ontario hosts David Bowie is after a blockbuster run at the Victoria & Albert Museum in Bowie’s native England. (You can see images from the V&A run here.) Over 300 objects—everything from handwritten lyrics to original costumes to photographs to film clips to music videos to set designs to Bowie’s own instruments and album artwork—appear together for the first time. The sheer range of styles and media blows the mind (and blows it further when you realize that Bowie’s own paintings and sculptures are left out). Bowie began as a musician who really wanted to be a painter and became a musician who acted, a musician who set fashion trends, and a musician who essentially created the music video as an art form. Michael Jackson may have made MTV, but Bowie made the music video into an art form, starting with “Ashes to Ashes,” the storyboards for which and the Pierrot costume designed by Natasha Korniloff that Bowie wears in the video appear in the exhibition. Seeing the music video play beside the costumes and other artifacts really impresses you with just how meticulous Bowie is with his work as well as how well he collaborates with other artists to achieve his effects.

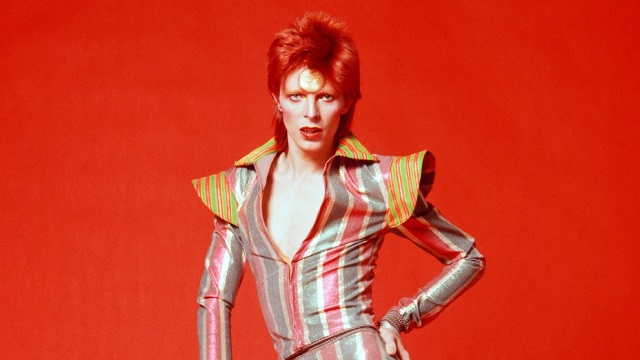

Bowie’s wide-reaching influence owes something to being in the right place at the right time. As music journalist Simon Price remarks in the same video, Bowie came “out of the 1960s at a time when all of the idealism of the 1960s had soured and died. A lot of people felt that these were end times–that we were looking at the end of the world.” In the middle of all that clock running out fatalism, Bowie comes along calling us to carpe diem. “[W]ith songs like ‘Five Years’– literally saying we’ve got five years left to live,” Price believes that Bowie’s “also saying it’s going to be a lot of fun, let’s celebrate the end of the world, let’s party in the ruins.” Thus, Bowie begins Ziggy Stardust and the whole Glam rock movement. Just as Picasso’s Cubism came along to deconstruct and reconstruct the shards of 19th century bourgeois existence, Bowie’s androgynous glam (as captured in photos such as Masayoshi Sukita’s 1973 shot above) not only cured the post-1960s spiritual hangover, but also ushered in an age of diversity and openness that inspired the gay rights movement to soldier on in pursuit of the victories they’ve won in more recent times. Amazingly, this one-man exhibit succeeds better in making the same point about pervasive societal influence of music and fashion that the Metropolitan Museum of Art‘s PUNK: Chaos to Couture (which I reviewed here) hoped to make.

David Bowie is is more than just museum pandering to popular tastes. Even the shallowest digging into Bowie’s art world connections brings up solid gold. Influences such as Surrealism, Dada, German Expressionism, mime, Kabuki, and others rise easily and irrefutably. Quotations from René Magritte, Sonia Delaunay, Gustav Klimt, Man Ray, and other figures strewn throughout art history appear in Bowie’s oeuvre, making him just as much a masterful magpie as Picasso himself. But within that multiplicity of influences and styles, Bowie always is Bowie—a pure artist open to any influence thanks to an unwavering confidence in his own vision.

The marketing for David Bowie is centers around a kind of “fill in the blank” campaign. David Bowie is this, or that, or something else. What this exhibition demonstrates is that he’s all of those things, and more. The present tense “is” isn’t just a marketing ploy. Bowie continues to influence and to create, so this isn’t the end of anything. Although the cover of Bowie’s 2013 album The Next Day quotes his own German Expressionist cover for four-decades-old Heroes, it sounds as new and fresh as anything out there. For Bowie, there’s always a next day, a new look, a new influence from the past to make relevant for the present. David Bowie is, if nothing else, a celebration of creativity itself, of how an individual can transcend labels and the anxiety of influence to create something new that inspires others to join in the fun. To paraphrase from the title track of Heroes, We can be Heroes of the spirit to create, forever and ever. What do you say?

[Image:David Bowie (detail), 1973. Photograph by Masayoshi Sukita. © Sukita/The David Bowie Archive.]

[Many thanks to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, Canada, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to David Bowie is, which runs through November 27, 2013.]