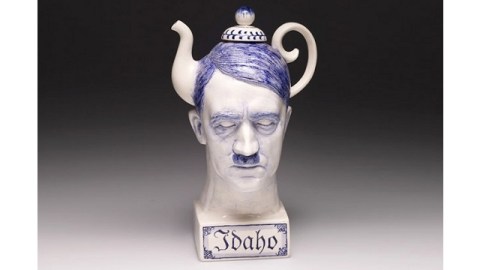

Is Charles Krafft’s Nazi-Inspired Art Ironic or Not?

Artist Charles Krafft’s enjoyed a dark, edgy, “don’t you see the irony” reputation for more than 20 years now. Krafft’s Nazi-inspired ceramics (such as his portrait bust of Adolf Hitler’s head turned into a teapot titled Hitler Idaho; shown above) appear in exhibitions and museums across America. Krafft craftily played with your gut reaction of repulsion from the vile dictator turned into a genteel tea time accessory. But more than a tempest in a teapot has been brewing in the wake of an interview in which Krafft denied the reality of the Holocaust in which the Nazis exterminated approximately 6 million Jews. Suddenly, the irony of works such as Hitler Idaho’s not just lost on some people, but apparently lost from the work itself. Did Krafft’s statements transform his work from farce to fetish? Is Charles Krafft’s art ironic or not?

Admittedly, Krafft’s work takes a moment to absorb. Perfume bottles marked “Forgiveness” with swastika stoppers strike an unsettling note for anyone not sympathetic to Nazism or White Supremacy. Krafft also specializes in personalized mementos of death in which he mixes the cremated ashes of the deceased into the ceramics he creates. Many have commissioned works from Krafft in which their loved ones sit on a shelf encased in one of his creations. How many wish they could reverse the process now?

According to the original piece in The Stranger, Krafft’s public transformation into a Holocaust denier began with a Facebook post. “Why amongst the monuments glorifying the history of this nation in Wash DC is there a museum of horrors dedicated to people who never lived, fought, or died here?” Krafft asked his 2,000 Facebook followers. “The [United States Holocaust Memorial Museum] was erected before there was ever a monument to the 465,000 Americans who died in WWII. And no one did enough to save the Jews of Europe?” That strange statement led The Stranger’s intrepid reporter Jen Graves to contact Krafft and ask if he was a Holocaust denier. Krafft replied that “[u]nless it has some relevance to art that I’m currently exhibiting… I see no reason to answer the loaded question ‘Are you a Holocaust denier?’” Of course, that non-answer only made the real answer more vital and relevant to him and his art.

Refusing to accept Krafft’s evasion, Graves dug deeper to discover that “you can find Krafft narrating his philosophy in his own voice just by doing a little googling.” She found that Krafft participated in podcasts of The White Network, a white supremacy group I refuse to link to, at least as far back as 2012 and probably earlier. On the 2012 podcast, Krafft confesses that he “believe[s] the Holocaust is a myth… being used to promote multiculturalism and globalism.” Krafft goes on to call Holocaust acceptance a “new secular religion” aiming to overshadow Christianity by drowning out Christ’s singular sacrifice with that of 6 million victims. “[I]t’s all part of the promotion of a new kind of… civil religion maybe,” Krafft says of the museums and scholarship surrounding memorializing the Holocaust. “We’re the heretics in a new religion that’s being promoted and built up and being embraced by governments throughout the United States and Europe.”

Confronted with this evidence by Graves in a repeated asking of the denial question, Krafft finally admitted via e-mail that “I don’t doubt that Hitler’s regime killed a lot of Jews in WWII, but I don’t believe they were ever frog marched into homicidal gas chambers and dispatched. I think between 700,000–1.2 million Jews died of disease, starvation, overwork, reprisals for partisan attacks, allied bombing, and natural causes during the war.” In follow-up interviews, Krafft’s tried some damage control or at least clarification of his views, but never really wavered from his central stance that Hitler’s still evil, but not Holocaust-responsible evil.

So, what does this mean for the art itself? Hitler Idaho, purchased by a Jewish art collector and donated on his passing to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, seems an ideal example to put to the test. The wall text for the piece reads, “Charles Krafft’s Hitler, Idaho resurrects the image of Adolf Hitler to critique fascism and the role of kitsch. The teapot spout and handle resemble devil-like horns, suggesting that Hitler was a demonic and evil being. The Germanic Idaho inscription alludes to that state’s reputation as a refuge for racist neo-Nazi groups such as the Aryan Nations. The teapot lid doubles as a yarmulke, a reference to revelations that several white supremacists were of Jewish heritage.” If Krafft himself associates with the neo-Nazi groups of Idaho and elsewhere and denies the demonic characterization of Hitler, then what is this work really about? Is the yarmulke-esque lid no longer an ironic reference to the Jewish heritage of some white supremacists but rather a mocking jab at Jewish people?

There are some, such as Russell Smith of The Globe and Mail, who think we should forget Krafft’s words and just remember the art itself. “Let’s ignore Charles Krafft, the person, completely. He’s a goof,” Smith suggests. “His art is weirdly powerful, perhaps despite his intentions.” It’s the ages-old question of authorial intent gone wild and many will take the side that the author’s intentions don’t matter. Unfortunately, in this case, it seems to me that the author’s intentions are as embedded into these works as much as the ashes of his memorialized patrons.

Yes, there’s a weird power to these works, but what’s the nature of that power? Is it the power to mock evil in its most concentrated form or is it White Power sticking its tongue out at what it sees as a Jewish conspiracy? Has Krafft been, in his eyes, countering the Holocaust conspiracy with a conspiracy of his own to get these anti-Jewish works into museums, sometimes with the patronage of Jewish collectors? If the African-American artist Kara Walker were to reveal herself as a “beard” for some racist bigot tomorrow, then her powerfully honest works showing the violence, especially sexual, of slavery would instantly become the sick fantasies of a diseased mind. If context is central to a work, then I don’t think you can dismiss it as easily as some wish they could. To deny the implications of Krafft’s denial on his art is just another kind of denial, in this case of the reality of such views still existing in civil society. Krafft tries to soften the edge of his new image, calling himself a “skeptic” rather than a denier and “a white advocate” rather than a white supremacist, but the damage is done. The irony of Krafft’s works is lost, but a new irony is born if those who embrace the mind-opening power of art allow such close-mindedness to stand unopposed.

[Image:Charles Krafft. Hitler Idaho.]