Human Nature in the Lab and on the Page

We live in an era where readers of science books on the human condition expect clever psychological studies to explain every nook and cranny of our complex nature. They expect specifics, what happens in the brain when musicians improvise or when we experience a-ha moments, and they expect generalities, how friendships form or how decision-making works.

Readers also want surprise. A good author declares how a commonly held intuition about human nature is, after all these years, untrue in the face of overwhelming empirical evidence. Gladwell did it beautifully in Blink. “We live in a world that assumes that the quality of a decision is directly related to the time and effort that went into making it,” he states in the introduction. “[But] decision made very quickly can be every bit as good as decision made cautiously and deliberately.”

Or considerJonah Lehrer in How We Decide:

Ever since the ancient Greeks, [we’ve assumed that] humans are rational…. There’s only one problem with this assumption of human rationality: it’s wrong.

Or Geoff Colvin in Talent is Overrated:

We still say that [people] have a gift, which is to say their greatness was given to them, for reasons no one can explain, by someone or something apart from themselves… the trouble with this explanation… is that it’s wrong.

Readers also crave drama. An effective introduction positions society as nearing a time of momentous change, in which ignoring a certain area of study will lead to irreversible errors. My favorite example of this comes from Susan Cain, who said this about introverts to a TED audience:

[Ignoring introverts is] our colleagues’ loss, and our community’s loss, and at the risk of sounding grandiose, it is the world’s loss.

When did human nature get so awe-inspiring?

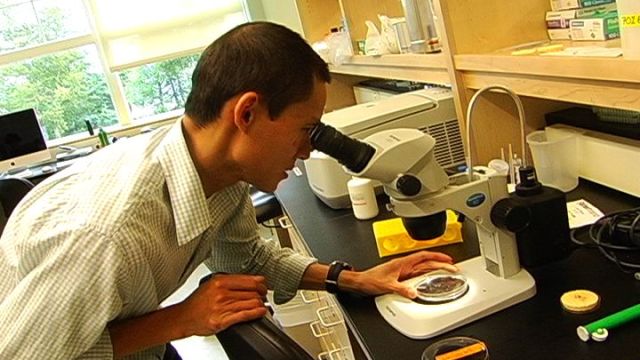

Cognitive science exists in a golden era. The amount of resources pouring into research that examines human nature is unmatched by any other time in history. As a result, science writing is experiencing a golden era of its own. Scores of books with a new perspective on human nature are published every year because science writers have a lot of material to work with.

This relationship is reinforcing: thought-provoking research ends up in bestselling books putting pressure on researchers to produce rousing results of their own. Science writers, in turn, dig deeper for the latest counter-intuitive research. Wanting in on the action, young science writers and scientists are throwing themselves into the mix.

Is this a good for each industry?

A few months ago I corresponded with behavioral science professor Dave Nussbaum who teaches at the University of Chicago. He riffed on similar talking points and his response is worth reading.

There’s been a rise in research that’s aimed at creating a stir, sometimes at the expense of the soundness of the research. At the same time, I think done properly, “cool” and counter-intuitive findings are very important. They not only get us to think in a different way, they also make it much easier to tell an engaging story about psychology, and I think that’s an important thing to do. There’s been a huge rise in the interest of the general public towards psychology, and I think that’s great. Imagine, Power of Habit, and Thinking Fast and Slow are all on the bestseller list, and in the last decade the number of great psychologists… who are getting their important research out there for the public to consume is way up. There are downsides, too… but on the whole I think it’s extremely positive. O

One consequence, as you rightly worry, is that it creates a bad system of incentives for researchers. It’s not just the books, of course, it’s also some journals that are motivated to publish eye-catching work. There are upsides to this, but the big downside is that you’re publishing unreliable or incorrect findings and in a field where sometimes you don’t get much replication, you’re polluting our knowledge. Worse still, these studies get all the attention, while more careful but no less important research is ignored, while being more costly to run and less rewarding. Not really sure what to do with this problem other than to try to be more careful.

As a science writer I’m not sure either. Two ideas. First, psychological science is young. Counting from Wilhelm Wundt’s first experiments it’s only about 150 years old. Other cognitive sciences – neuroscience, linguistics, and modern sociology and anthropology – are even younger. I’ve interviewed several psychologists and it’s not uncommon from them to respond to questions like this: “You know, there’s no real evidence of this in the psychological literature. There are just not that many people studying that.”

Second, when it comes to writing about psychological research it’s probably best to do what a good teacher does. He won’t give you answers per se. He will suggest a style of thinking that will help you see the world more accurately. This is not to suggest that we shouldn’t expect psychological science to continue pursuing specific questions. But it is to recommend a moment of humility when it comes to understanding human nature.

Finally, Dave reminded me in an email yesterday that science is always a work in progress and that it’s much more exciting to tell a story that isn’t over. “That’s what I would imagine would excite young readers,” he said. “The opportunity to be able to contribute something to the answer. There’s plenty of room to give people interesting (interim) answers to good questions without pretending like the book has been written and there’s nothing more to add.”