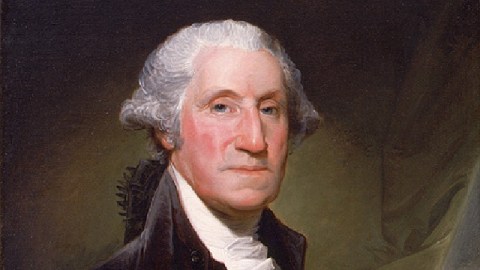

George Washington: Founding Father of American Art?

“First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen”: those famous accolades have followed George Washington—first U.S. President and the beardless half of today’s Presidents’ Day holiday—since the very beginning of his transformation from man to myth in the American pantheon. Could Washington have been first in American art, too? In George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon, Joseph Manca aims to rehumanize Washington by “reassess[ing] his place in early American intellectual life,” specifically in the realm of art. Just as Washington helped America gain political independence, he helped foster an independent American art culture, knowing that there was more to being a nation beyond bills and bullets. Was George Washington the founding father of American art?

Washington’s artsy side usually gets overshadowed by that of his “cultural virtuoso” (Manca’s phrase) contemporary, Thomas Jefferson. How can you compete with the architectural maestro of Monticello, the prose poet of the Declaration of Independence, and connoisseur of everything from fine wine to fine art? (Jon Mecham’s Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power not only puts “art” right there in the title, but also demonstrates just how integral the arts were to Jefferson’s performance in all the theaters of his life.) Don’t sell Dollar George short, Manca argues. “George Washington was deeply interested in art, architecture, and landscape gardening,” Manca counters, “hop[ing] that this book shows the breadth and depth of Washington’s artistic creations and interests.” An architect in his own right, as well as an innovative gardener and forward thinking art collector, the George Washington seen through Manca’s eyes emerges as a strong challenger to Jefferson’s aesthetic crown.

Where Jefferson had Monticello, Washington had Mount Vernon. Although many historians downplay Washington’s role in the designing of Mount Vernon, Manca arrives at a more balanced view, seeing Washington as “both an architect and a patron of the mansion house, contributing his ideas only so far as his talents and availability allowed… [by] providing plans and instructions but also depending on craftsmen for their expertise, especially in putting on the finishing touches.” Washington saw Mount Vernon as the architectural manifestation of his own persona—strong, simple, distinguished, and uniquely American. Manca devotes an entire chapter to Mount Vernon’s portico, the Eastern façade with the majestic view of the Potomac River (and even gives over another whole chapter to how Washington orchestrated that view to maximum effect).

Calling that portico “Washington’s greatest contribution to American architecture,” Manca demonstrates how “with its combination of the colossal order and the full extent across the façade, there was no other porch like it in America.” Influenced by English architecture, which was influenced by the classical model of the Roman porticus, Washington tweaked the design to make it his own. “The porch at Mount Vernon is the result of Washington’s desire for innovation within the larger sphere of classical revival,” Manca concludes, “and it is the product of his admiration, not imitation, of antiquity.” As with nearly every other facet of his life, Washington reached into the near and classical past for the raw materials for his drive into the still-nascent American future. Where Europe represented excess and decadence, Washington (and his home) would represent simplicity and honor.

The same tension between classicism and innovation appears in Washington’s role as gardener. “Washington’s gardens were not slavishly beholden to English theory or practice,” Manca explains. Rather, “he shaped his landscape into a consciously personal form that expressed his unique place in American society.” Manca expertly situates Washington the gardener into the context of the English school of gardening, especially as interpreted by Capability Brown. Even if you’re not an aficionado of gardening, the way that Manca connects Washington’s gardening to the architecture of Mount Vernon—mirroring the way Washington himself wanted them seen as a continuous, organic whole—makes for compelling reading. Washington would even have whole swaths of trees removed to make for better views from the house, especially the epic porch. “The result demonstrates Washington’s skill as a landscape artist working successfully with the natural and man-made elements to create views replete with pictorial variety, framing, and spatial distancing,” Manca sums up. (Beautiful color plates in the book do their best to convey some sense of the breathtaking effects Washington achieved.) Washington the former surveyor and battlefield tactician continually surveyed the ground before him and won the battle to express his vision through carefully orchestrated nature.

Washington’s love of physical landscape easily translated to a love of landscape painting—a taste that not many other collectors of the time shared. Blessed with a “good eye,” Washington lacked the vocabulary of an art connoisseur but was still able to recognize good work. Landscapes Washington purchased from artist George Beck and others still hang on the walls of Mount Vernon today. Knowing that foreign diplomats and other dignitaries would enter his halls, Washington carefully chose artwork that would convey a sense of America as cultured and refined as Europe, but still uniquely American. In fact, Washington’s taste for landscape “was highly unusual,” Manca argues, “and foretold of the rise of that genre in the Romantic period and the nationalizing sentiments expressed in the Hudson River School and beyond,” giving credence to Washington’s claim as the founding father of American art, or at least a man ahead of his time. Manca delves deeply into Washington’s art collection to unearth both the sacred and the profane: a portrait of the Virgin Mary that would have been quite unusual for a Protestant’s collection at the time, as well as a print of bathing nymphs discreetly hung in a second floor bedroom.

I especially enjoyed Manca’s analysis of Washington’s relationships with artists. Washington favored artists such as Charles Willson Peale and John Trumbull both for their talents and their fine moral character. Less upstanding artists, such as the frequently tardy Gilbert Stuart (creator of the Washington portrait shown above) tried the President’s patience. When Jean-Antoine Houdon came to sculpt Washington’s image, Washington took notes on the sculptor’s process of working with plaster, which he found fascinating—a sign of the insatiable intellectual curiosity usually credited to Jefferson, but rarely to the first president. When asked by Houdon if he preferred classical or modern dress for his full-length statue, Washington chose modern dress as simpler and, hence, more American.

The artsy side of presidents is always a difficult thing to measure. The discovery that 43rd President George W. Bush has been painting bathroom-situated self-portraits may be more surprising than the depiction of 1st President George Washington’s artistic side, but only because of the distance of history. Like the innovative 16-sided barn Washington designed, which Manca praises for its “cathedral-like beauty and complexity to the interior, aesthetically pleasing but also necessary,” Washington’s relationship to art as outlined in George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon was both aesthetically pleasing and necessary, but all in a complex, cathedral-like web of subtle and subtly beautiful associations. Instead of art for art’s sake, Washington deployed art in the struggle to create a new nation both in the sense of aesthetic culture and in the sense of shaping a national identity separate from yet equal to or better than that of the old world. In George Washington’s Eye, Joseph Manca convincingly argues that George Washington, the “indispensable man,” was indispensable to American art, too.

[Image:Gilbert Stuart. Portrait of George Washington (detail), 1795. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image source.]

[Many thanks to The Johns Hopkins University Press for providing me with a review copy of Joseph Manca’s George Washington’s Eye: Landscape, Architecture, and Design at Mount Vernon.]